Definition

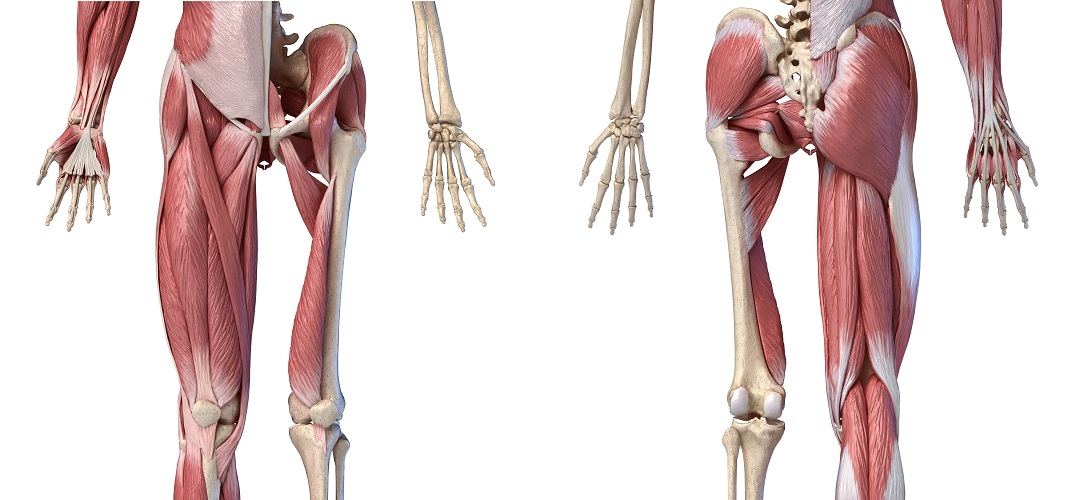

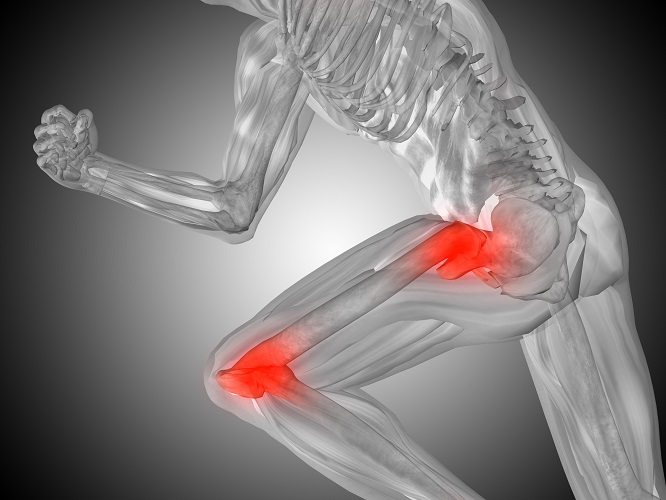

Hip muscles are skeletal muscles that enable the broad range of motion of the ball and socket joint of the hip. These movements are hip flexion, extension, adduction, abduction, and rotation. There are nearly twenty different muscles that contribute to hip movement patterns; these muscles play roles as agonists, antagonists, and synergists to move and stabilize the hip joint during these various movements.

Anatomy of the Hip Muscles

Hip muscle anatomy is a complex topic. This is because there are so many different muscles that give our hip joints a full range of motion. The hip muscles are composed of multiple flexors, extensors, adductors, abductors, and rotators that work together. When we talk about the muscles of the hips, we are discussing a very broad group. This can seem quite intimidating. By practising some of the exercises described at the end of this article, you integrate theory with actually feeling the individual muscles contract and relax.

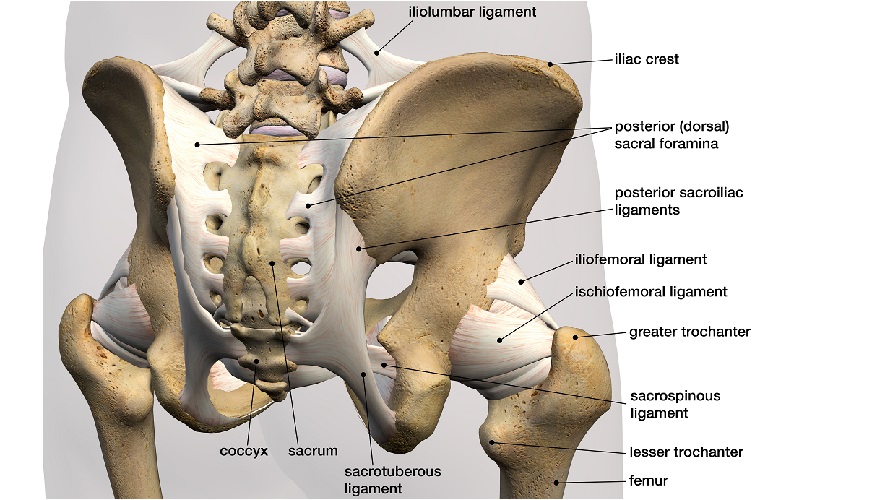

The hip muscles surround the hip joint – a ball and socket joint between the femur (thigh bone) and three fused (in adults) pelvic bones – the ilium, pubis, and ischium. At the top of the femur, an angled, rounded head is supported by the femur neck. The femus head is hidden by the ilio- and ischiofemoral ligaments in the next image.

To the other side is the bulge of the greater trochanter, a point for muscle and tendon attachment that you can usually feel through the skin. At the opposite side of the greater trochanter, a little lower so that it sits under the neck, is the lesser trochanter. The word trochanter refers to these bony outcrops. The lower end of the femur forms the top of the knee joint.

The femur head fits into a similarly rounded indentation in the pelvis, at the bottom of the wing-shaped ileum and the top of the ischium and pubis bones. As the above image is a back view, only the top edge of the ileum – the iliac crest – is indicated. By around eight years of age, the ischium and pubis have fused. The ileum fuses to the ischium and pubis – at the acetabulum – in the early teenage years. This fusion occurs earlier in females.

As with all joints, a degree of cushioning is required to stop the two bones from grinding against each other. The hip joint is a synovial joint – a very generic diagram of a synovial joint can be seen below. In this type of joint, the working ends of the bones are surrounded by a membrane and inside this membrane is a thick fluid called synovial fluid. The femur head and inside of the acetabulum are also coated with a thick, very smooth layer of articular cartilage. The combination of fluid and cartilage allows painless, smooth movement of the joint. When the cartilage is damaged or the synovial fluid is infected, movement at this joint becomes very painful.

Synovial fluid is produced by the synovial membrane, the cells of which produce a thick, gooey byproduct of blood plasma combined with lubricants and thickeners such as hyaluronic acid and the aptly named lubricin. Tiny areas of cartilage damage can be smoothed over as this gel can run into shallow indentations, in the same way as a facial blur cream fills pores to produce smoother skin.

Our hip joints must withstand extremely high pressures. A study using artificial model joints based on human anatomy showed that these forces are much greater than previously thought – when landing after a vertical jump the hip joint must deal with compression forces of more than eight times the body weight; the hips of a a one-hundred-and-sixty-pound man would need to support a force of nearly 1,300 lbs. Just standing still produces a compressive force of more than double the body weight.

You may think that this force would be shared equally between both hips; however, joint compression in each hip can be anywhere from 75 to 100% of the total body weight. The surrounding ligaments and muscles also provide continuous forces, which may explain why each hip must deal with more than 50% of the load. Postural changes and joint degeneration can also change the load on one side.

If someone suffering from hip pain is quite short and weighs 250 lbs, losing fifty pounds could postpone hip replacement surgery – each hip joint will only need to support between 300 and 400 lbs when standing, instead of up to 500 lbs. And we tend to spend a lot of time on our feet.

Our hip muscles work in groups, some contracting and others relaxing as muscle agonists and antagonists. Some muscles have minor roles in particular movements where they support the prime movers (the primary agonists) – when they play a supporting role, muscles are known as synergists.

Each muscle group contributes to certain types of movement. It is simpler to look at the different ranges of motion and describe which muscles play a role rather than list each muscle as a separate entity. Different patterns of movement should be well understood, together with specific terminology. The hip muscle diagram below shows a number of the muscles we will be discussing in the next sections.

Hip Flexors

When you flex your hip, you move the leg forward. Hip flexion is maximal with a high, forward kick that brings the leg above the level of the waist. More commonly, our hips flex to a 90° angle when we sit in a chair; the lower the seat of the chair, the greater the flexion. Walking also requires hip flexion. It does not matter whether the knee bends or not; only flexion provided by the hip muscles is discussed in this article.

The prime mover (agonist) for hip flexion is the psoas major muscle. This is a long, tapering (fusiform) muscle that originates at either side of the spine and inserts at the lesser trochanter of the femur. The psoas muscle contracts when the hip is flexed.

The other prime mover is the iliacus muscle. The iliacus muscle is a triangular sheet that connects the iliac bone to the lesser trochanter.

As the iliacus is joined to the psoas major at the thigh, both are sometimes referred to as a single hip muscle – the iliopsoas muscle. The iliopsoas is the body’s most important hip flexor. If you spend the majority of the day sitting down, the muscle becomes shorter, tilting the pelvis, and can change how you walk.

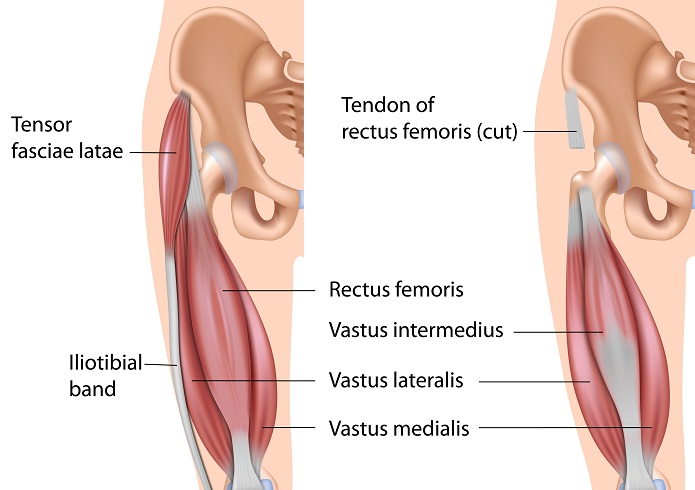

The rectus femoris also contracts during hip flexion, especially if the knee bends. This muscle is part of a muscle group called the quadriceps.

The next important agonist is the pectineus muscle that extends from the pubis of the pelvis to a point under the lesser trochanter. The psoas major, iliacus, rectus femoris, and pectineus all contract to move the hip joint forward.

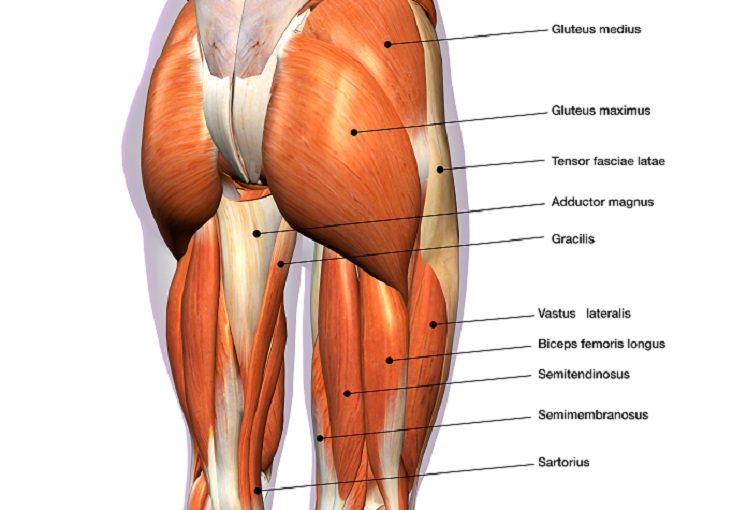

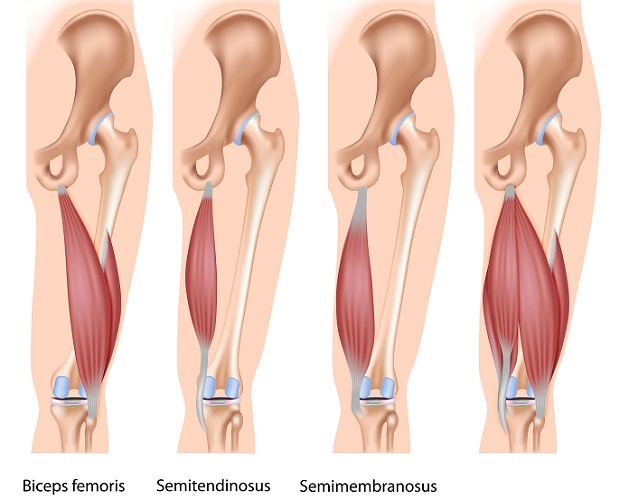

As these four muscles contract, others relax. A group of muscles that contributes to flexion is the hamstring. Although the hamstring muscles’ primary role is to flex the knee, it also assists during hip flexion. The hamstrings are a group of three muscles: the semitendinosus, semimembranosus, and biceps femoris (long head). As the psoas major and iliacus muscles contract, this group relaxes. The hamstrings are, therefore, antagonists.

The other antagonist for hip flexion is the gluteus maximus. This is a large, thick muscle that covers the buttocks and tapers around the hips to insert at two ridges located approximately halfway along the front of the femur.

Many other muscles contribute minor supporting actions to stabilize the joint when being flexed. These will prevent the joint from inward or outward rotation and help to keep the hip in a flexed position for long periods.

Hip Extensors

Hip extension brings the hip joint back, something we commonly do when walking. While flexion is a step forwards, extension describes the position of that hip after the other leg has taken a step. The angle of hip extension is important – a larger angle helps to prevent falls. While the average young adult extends the hip by approximately twenty degrees at a comfortable walking speed, elderly people have been reported to have an extension angle of as low as six degrees.

While the gluteus maximus is an antagonist for hip flexion, in hip extension it is the primary mover. It contracts to bring the leg back – you can feel the large muscle in the buttock area pull as you walk.

The hamstrings are agonists during both hip flexion and extension, but the most important antagonists are the psoas and iliacus muscles. This makes complete sense, as these muscles contract to bring the hip joint forward, and should, therefore, relax during the opposite movement. By learning the names of the prime movers and antagonists of one movement, you can usually swap them around to give the names of the agonists and antagonists of the opposite motion.

Hip Adduction

When the leg is brought back towards the midline or the opposite side of the body, for example, if you cross one leg in front of the other when line-dancing or if you kick a soccer ball with the inside of your foot, you are adducting your hip.

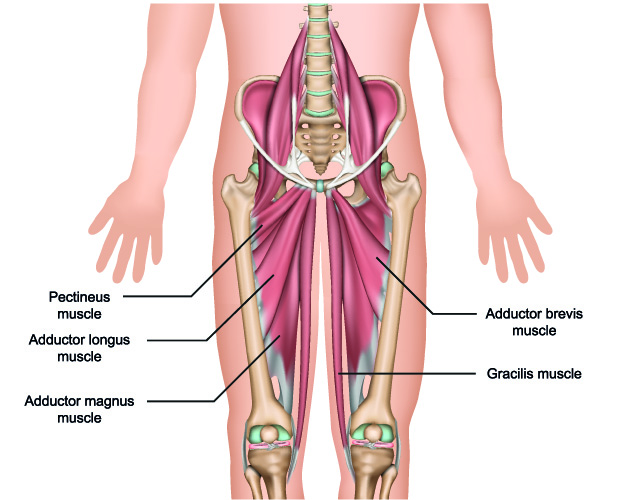

There are five primary movers for hip adduction but these are simply referred to as the adductor group. The adductor group consists of:

- Pectineus muscle

- Gracilis muscle

- Adductor magnus

- Adductor longus

- Adductor brevis

The pectineus is a flat, wide ribbon of muscle that joins the pubic bone to just under the lesser trochanter of the femur. You may remember that it is also an important agonist in hip flexion. Many muscles of the hip play roles in multiple movement patterns. The muscle fibers of the pectineus run at angles to each other, meaning that when you adduct the thigh you automatically bring it a little forward (flexion).

The long gracilis muscle crosses both the hip and knee joints from a pelvis origin. In the hip, the gracilis contracts to bring the hip (and knee) towards the pelvis.

The adductor magnus is a wide, deep, almost triangular sheet of muscle that runs almost as far along the femur as the gracilis. Magnus, longus, and brevis give us an easy reference – the main adductor muscle is the longest of the three, the longus is a little shorter than the magnus, inserting about halfway along the femur, and the brevis is the shortest and inserts just under the lesser trochanter.

Hip Abduction

To abduct is to take away. When the hip moves horizontally away from the midline, it is being abducted. The fatter the horse you sit on, the more your hip joints need to abduct.

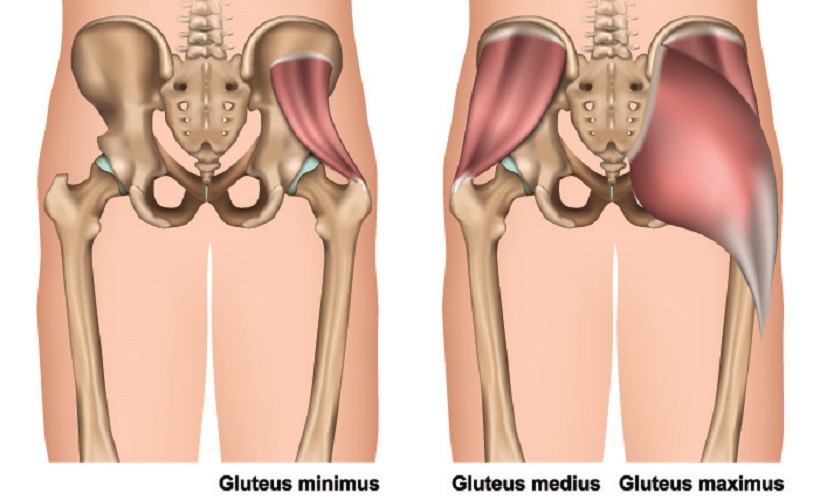

The prime mover for hip abduction is the gluteus minimus – a deep, small muscle within the buttocks that originates quite close to the crest of the ilium bone and extends to the greater trochanter (the part of the hip bone you can feel on the outer side of your hip). If you image the muscle as a half-open fan, the handle is at the trochanter and the fan spreads along the flat surface of the pelvic ilium.

The gluteus medius lies immediately above the gluteus minimus and is also fan-like in shape with similar origin and attachments. Both the medius and minimus contract to bring the greater trochanter up towards the iliac crest – abduction. Even though it is the largest of the gluteal muscles, the gluteus maximus only plays a synergist role during this movement.

Hip Internal Rotation

Internal rotation of the hip joint involves turning the hip inwards so that the greater trochanter comes towards the front of the body. The best way to do this is to twist one knee towards the other.

The gluteus minimus, as its name suggests, is the smallest of the three gluteal muscles and lies beneath the other two muscles in the buttock region. This is the prime mover of internal rotation of the hip. This joint can turn towards the pelvis at a maximum angle of approximately 45° and, as you will probably have realized, a certain degree of rotation also occurs during other hip movements. When we consider that the hip joint is a ball and socket joint, this is easy to explain – the rolling action of the joint means that a lot of rotation is involved. Many synergist muscles limit rotation during adduction, abduction, flexion, and extension.

Internal rotation has one prime mover but around nine other hip muscles assist in this movement. These include the gluteus medius, adductor muscles, and tensor fascia latae (TFL). The TFL is a fusiform (tapered) muscle of about fifteen centimeters in length that attaches the lower spine and iliac crest to the tibia (top of the lower leg bone), running over the hip and greater trochanter. This muscle acts as a synergist for multiple hip movements but is primarily a rotation muscle.

Hip impingement or femoroacetabular impingement can prevent internal rotation due to high levels of pain. When left untreated, this can lead to osteoarthritis of the joint. Hip impingement is common in all ages and especially in the athletic community. When bone at the edge of the acetabulum is misshapen, either as a congenital disorder or over time, the result may be pincer impingement. If it is the femur head that grows incorrectly, the result may be cam impingement. These bony outcrops mean smooth movement is not possible and, over time, the cartilage becomes damaged. It is no longer smooth and causes friction. Areas can become so thin that the femur head and acetabulum rub against each other.

Hip External Rotation

The primary mover for external rotation is the gluteus maximus. You can easily remember the prime rotators with “a small (minimus) internal rotation and a large (maximus) external rotation at the buttocks (gluteus)”.

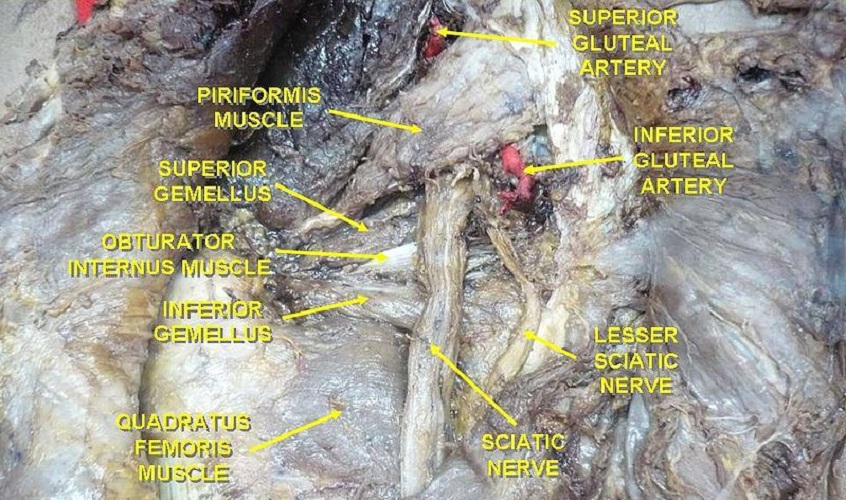

There are six outward rotator muscles – the gluteus maximus, obturator internus, superior gemellus, inferior gemellus, quadratus femoris, and obturator externus.

The gemellus superior, gemellus inferior, and obturator internus muscles form a group called the triceps coxae. The triceps coxae are hip rotators and general hip stabilizers.

Muscles that assist in rotation include the iliopsoas, sartorius, and biceps femoris of the hamstrings. Finally, the piriformis – a flat and superficial muscle under the gluteal muscles – allows rotation when standing (when the hip is in extension) as well as pelvic tilting.

Knowing the names of every hip muscle is rarely necessary, but many athletes like to know exactly how to exercise and warm-up. By understanding how each muscle contributes to hip range of motion and how these muscles cross the hip joint, unnecessary injuries can be avoided. This Michigan State University list provides a quick overview of the various muscles involved in hip range of motion.

Hip Muscle Pain

Hip pain can affect different anatomical points and affects both young and old populations. The very young usually suffer from congenital disorders due to bone abnormalities – the femur head can slip out of the acetabulum. The general term used for a wide range of structural anomalies is pediatric hip dysplasia. Hip dysplasia is common in some types of dogs, and the shallow sockets of the labrador retriever are very obvious in this x-ray.

Adolescent hip pain may also be the result of congenital problems that have worsened over time. Other causes are infection of the synovial fluid, juvenile arthritis, and damage to the still-growing bones that can cause changes in their shape.

Most commonly, adolescent hip pain is the result of muscle injury that occurs during sporting activities. If you only play sport occasionally, the chance is higher that you will tear or strain a muscle. Professional athletes always include a warm-up and for good reason; if you are suddenly invited to join a basketball game, the lack of a warm-up could put you at high risk of injury.

Labral tears – tears in the cartilage of the ball and socket joint – are common in ballerinas. Rotation of the hip can make an audible clicking sound. In labral tears, possible undetected bone abnormalities or exaggerated hip movement cause splitting in the cartilage and the joint no longer moves smoothly, ‘catching’ on the tears that run across the normally smooth articular cartilage. Most labral tears require surgery.

Adult hip pain can be the result of injury (hip muscle strain during a workout or long walk) and the degeneration of bone and cartilage. The longer we use our hips, the more likely that the cartilage becomes pitted and the bones less dense. When hip pain becomes continuous and is not just the result of a pulled hip muscle, the best solution is hip replacement surgery.

Generalized causes of hip pain that affect all ages include bursitis and tendonitis. A bursa is a fluid-filled compartment that protects surrounding muscles from tearing on the bone. Hip bursae cover the greater trochanter (trochanteric bursa), the lesser trochanter (iliopsoas bursa), and the insertion point of the gluteus medius (gluteus medius bursa). Bursitis is usually a continuous pain that is treated with anti-inflammatory drugs, ice compresses, and rest.

Tendonitis is usually most painful when flexing the hip. Muscle tendons attach muscle to bone and can also stretch or tear, often only to a very small degree. If at the first signs you rest the joint, damaged tendons have time to repair. If you continue to actively use the hip joint during a sporting activity or regularly climbing stairs, damage will not only requires a much longer time to heal, the weak spots are likely to tear even more. Tendonitis can be extremely painful. When the hip muscle tendons are inflamed, even gentle walking can be excruciating. Again, anti-inflammatory drugs, ice compresses, support, and rest are advised.

Sore hip muscles – not sore hip joints – can be treated through rest and then gentle exercises. The last section of this article covers several hip muscle stretches that nearly anyone can do. Tight hip muscles are caused by shortening, usually through long periods of inactivity, sitting-down jobs, and bad posture.

Hip pain can affect other areas of the body. This is then called referred pain. Damage to the lower spine can cause referred pain in the hip, even if the hip is in top condition. Alternatively, a damaged hip can cause pain in the knee of that leg.

Treatment for Hip Muscle Pain

Hip muscle pain treatment depends on the cause of the pain. Due to the numerous muscles of this extremely mobile joint, diagnosis is not always simple.

If your hip pain begins the day of or day after mountain-climbing, skiing, horseback riding, or any other activity that actively requires lower body muscles, you can usually come to the correct conclusion. RICE therapy – rest, ice, compression, elevation – is the best treatment. If this does not improve your condition after two to three days and the pain prevents some movements, a visit to your local doctor is advised. To prevent further injury, hip muscle exercises should be part of your daily to weekly routine. Some extremely worthwhile exercises are described later on.

Infections such as bursitis usually go away thanks to the body’s natural immunity. Making sure your body gets the nutrients it needs to fight infection through a healthy diet could speed up the process. Anti-inflammatories and cortisone can reduce swelling but will not fight infection. If the number of pathogenic bacteria continues to multiply despite the action of natural immunity, antibiotics may be required. Bursitis may require a specialist to drain and disinfect the fluid sac under ultrasound guidance.

Chronic, low to high-grade pain could be a sign of bone or cartilage degeneration. Pain may be felt in the thigh, groin, at the hip joint, or in the buttocks. The affected person may tend to avoid certain movements, although this will lead to muscle atrophy and make the condition worse. A lower range of motion may be a conscious choice to avoid discomfort or a result of hip degeneration. Most people will opt for over-the-counter medication. These products alleviate the pain but rarely treat the cause.

Blood tests to rule out rheumatoid arthritis, bone scans to check bone density, and medical imaging to look at the condition of the hip joint can point the way to the most effective treatment. This may be RICE therapy, specialized drugs, mineral therapy (calcium supplements), cortisone injections, low-impact exercise regimes to strengthen the hip muscles, or surgery (hip replacement). In obese populations, losing weight may help to significantly reduce chronic pain. Many morbidly obese people who opted for gastric bypass surgery have reported that they no longer suffer from hip, knee, and ankle pain after losing large amounts of weight.

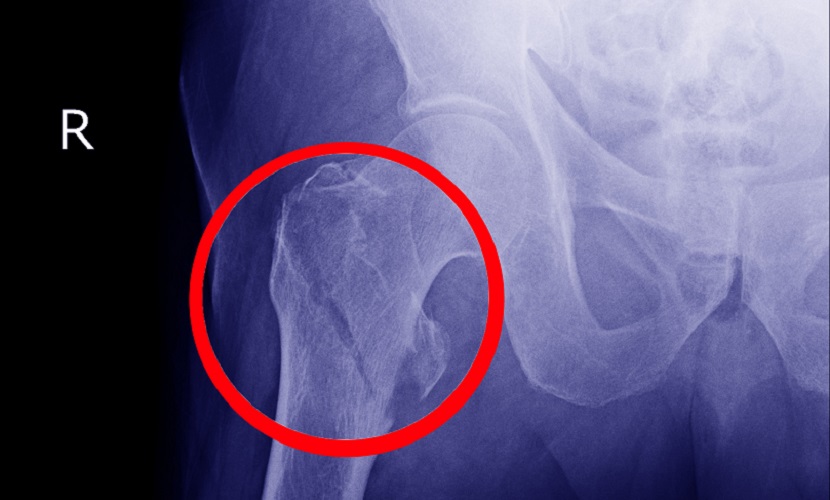

Sudden (acute) hip pain that prevents movement is probably due to dislocation or fracture. The latter particularly affects the elderly. The most common hip fracture type is the femoral neck fracture. The x-ray below shows a fracture through the greater trochanter, quite far below below the femoral neck. An overview of the different hip fracture types can be found on this University of Rochester Medical Center page. Often, a hip fracture will make the affected leg shorter than the other. Postoperative revalidation to strengthen the hip muscles is essential and can take weeks.

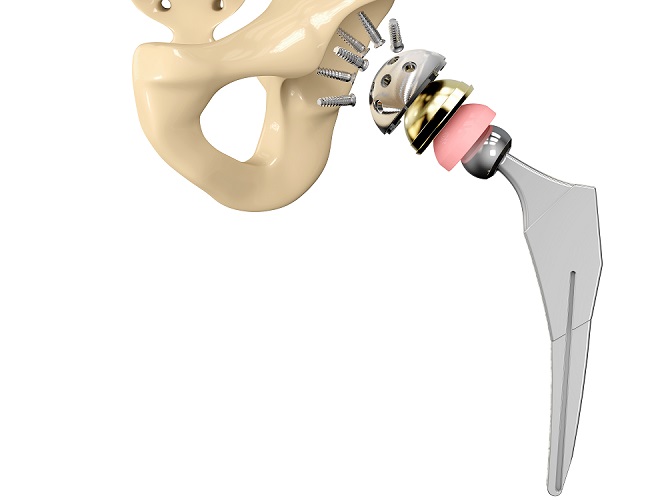

A hip fracture nearly always requires surgery. As most hip fractures occur in the elderly due to a lack of bone density, simply fixing the fracture is not enough. The area of the fracture will remain weak and will certainly not support continuous compression forces. This means that the damaged area must be replaced with a synthetic version – a hip prosthesis.

During hip replacement surgery, an orthopedic surgeon first removes damaged cartilage and thin layers of cartilage-producing bone from the acetabulum and femur head. Careful measurements must be made so the correct implant sizes can be selected. Metal or ceramic implants are shaped to mimic the natural, healthy cartilage of the hip joint. The femur head prosthesis includes an angled stem that is inserted through the middle of the long femur bone and a screw-on ball that replaces the damaged femur head. This ball fits perfectly into the acetabulum prosthesis. Both prostheses are temporarily fitted into place and tested for mobility before being permanently fixed into place. Finally, a plastic, ceramic, or metal spacer is fitted between both sections of the prosthesis. The spacer creates a very smooth, gliding surface between the acetabulum and femoral head and restores painless mobility of the joint.

New surgical techniques no longer require long cuts through the hip muscles. When the hip muscles are left more or less intact, they are able to support the new hip and shorten recovery times. If hip replacement surgery is planned, the patient will be advised to follow a light hip exercise regime well beforehand.

While many chronic hip pain patients try to put off hip replacement surgery for as long as possible, due to fears about how long the prosthesis is good for, many report wishing they had had the surgery at a much earlier point and saved themselves months or years of discomfort. This is not an ailment caused by the hip muscles but by bone and cartilage; however, the condition of the hip muscles can make the difference between success and failure of a replaced joint.

Electrical Hip Muscle Stimulation

Electrical muscle stimulation is not yet an accepted treatment for muscle pain but stimulation devices have been popular since the late 1970s.

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) is used to slow muscle atrophy and is still implemented by physiotherapists to help patients get out and about after surgery or long periods in a hospital bed.

Later on, electrical muscle stimulation was tested on Russian athletes. It was found that even in such healthy, active individuals, muscle strength was significantly improved. For a time, NMES for athletes was known as ‘Russian Stimulation’.

We have all seen various machines and devices on the market that allow everyone to train muscles while sitting down or even sleeping. By attaching electrodes to a single muscle or muscle group, electric pulses causes these muscles to contract and relax. Knowledge of hip muscle anatomy is essential when using such devices on this part of the body. How frequently and with what power these electric stimuli are given can be adjusted according to requirements. However, ‘over-the-counter’ devices do not have the same effects as professional (expensive) models and many suppliers of low-quality stimulators have been forced to take their devices from store shelves.

The FDA has received so many questions about electrical muscle stimulation that they have published an online FAQ. One question they do not answer is whether higher quantities of subcutaneous fat prevents electrical muscle stimulation from working – fat tissue absorbs some of the current and increases the distance between electrode and muscle; this means that the charge that reaches the target muscles may be reduced. It has been found that by using larger electrodes NMES can remain an efficient method of muscle contraction stimulation.

It seems that vibration rather than electrical hip muscle stimulation could help alleviate hip pain when this is not due to degenerative or infectious causes – for hip strain and muscle tears, for example. Massage guns use percussion (percussive vibratory massage) to reduce muscle soreness and stiffness, especially after a workout. It has been shown in limited studies that a five minute 50Hz massage-gun session has the same effect as a fifteen-minute traditional hands-on massage but is better at reducing lactate dehydrogenase levels for up to 48 hours after exercise. Both types of massage outperform no massage for pain reduction and increased range of motion.

Hip Muscle Exercises

Hip muscle exercises maintain or improve range of movement, protect against hip strain and hip muscle tears, strengthen the entire joint, and improve joint stabilization. Any workout should include a warm-up composed of hip muscle stretches. If you suffer from tight hip muscles, gentle stretches at regular intervals can loosen them. If you have had hip replacement surgery you should not attempt to flex the hip past 90° or lift your knee high, cross your legs, squat, or practice the internal and external rotation exercises. It is always best to ask your physiotherapist or surgeon for a list of gentle hip stretches that will not damage the repaired joint.

Whenever you take the time for a hip muscle stretch routine always make sure each movement remains comfortable and that your posture is correct. Incorrectly done, hip muscle stretches are renowned for causing muscle and tendon tears, especially in the groin region, hamstrings, and deep in the buttocks.

Hip Flexor Exercises

You can exercise the hip flexor muscles sitting down. Sit straight and ensure your posture is good by imagining a string attached to the top of your skull that pulls your back upright. Both feet should face forward. Lift one knee so that the angle of the hip is above 90°. As the flexor muscles become stronger, you will be able to lift the knee higher and keep it there for longer. Keep the leg pointing forward to avoid rotating the hip. Hold the position until this is no longer comfortable – by holding you are strengthening the associated synergist muscles. Lower the knee very slowly to the ground. Repeat at least ten times per side. Now do the same with the other leg. If you prefer, do this exercise while standing up.

If you want to add a little resistance, use an elastic workout band attached to a wall at ankle height. Place the other end of the band around one ankle Standing straight so that the band remains in place but offers no resistance, and facing away from the band, flex the hip forward to bring the foot forward and up. Keep the leg straight and keep rotation to a minimum. Hold this position and slowly return to the standing position. Repeat at least ten times, and then do the same with the other leg.

Hip Extensor Exercises

The gluteus maximus and hamstrings are important during hip flexion, so hip extensor exercises can be felt in the back of the thigh and buttocks.

The quadruped hip extension involves placing the flats of the hands and the knees on a mat with the tummy pulled in and the back in a neutral position. Lift one knee so that it follows the line of your body with the foot sole pointing to the ceiling. Hold this position for at least five seconds (to warm-up the synergist muscles), and then extend the leg at the knee so that the entire leg follows the line of the back and the sole points behind you. Hold for at least five seconds, flex the knee again, hold, and bring the leg back to the original position. Repeat at least ten times and then do the same with the other leg.

Hip Adduction and Abduction Exercises

Exercising both the adductor and abductor muscles is best done through squats. The Cossack squat requires you to place both feet wide apart and lunge using one leg at a time to the left and then to the right. Make sure you don’t lunge too far as the muscles of the groin could tear. The lunging knee should be at an angle of around 45° from the midline, while the opposite leg remains extended. Between ten to twenty repetitions is enough to get this double set of muscles warmed up.

Hip Rotation Exercises

The adduction and abduction Cossack squat also tones the rotator muscles of the hip, but to specifically work on your internal rotators, take a seat with both feet flat on the ground and both knees straight in front of you, about fifteen centimeters apart, and bent at 90° angles. Keep the back straight. Now rotate the hip so that the same knee comes towards the midline and the foot lifts slightly from the floor and moves away from the body. After at least ten repetitions, repeat with the other hip and leg. To make this exercise harder, place a workout band around the ankles or thighs. Remember to move from the hip and not from the knee or ankle.

To warm up the external rotators, stand straight with both feet facing forward and about fifteen centimeters apart. Lift the hip very slightly so that the foot is slightly above the floor. Turn your torso and head to the side opposite from the working leg and, using the hip, bring this leg around and back so that the foot points away from the hip. Do not bend the knee, just let it turn outwards. Hold this position for a few seconds. Return to the original position and repeat.

When doing hip rotation exercises, or any hip exercise type, it is important not to overdo it. The groin muscles are easily damaged, and many muscles that produce hip movements are thin and ribbon-like meaning they can overstretch and tear. A pulled hip muscle could mean a few days of RICE therapy and a lot of discomfort.

Quiz