Definition

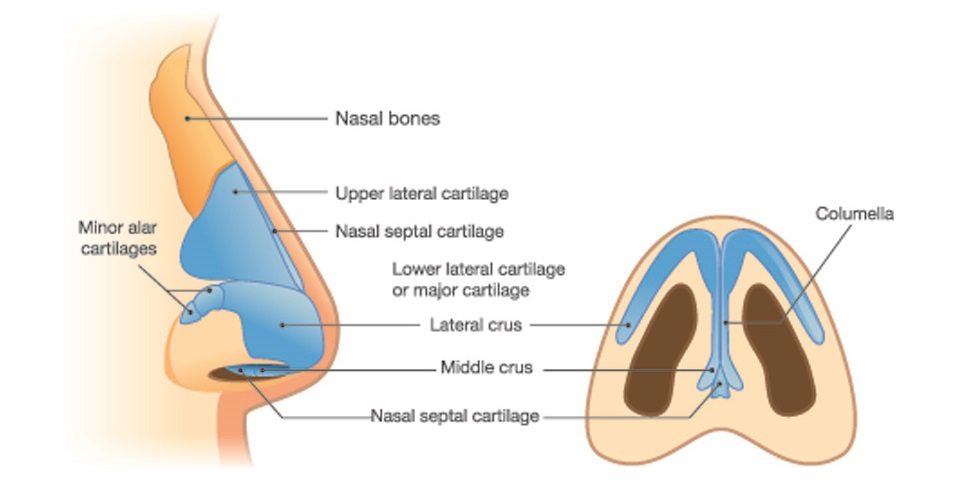

The nasal bone is a paired flat bone located at the upper third of the nose bridge. Each rectangular bone has an internal and external surface and four borders. These bones also feature holes (foramina) that allow veins to pass through from the skin. The thinner inferior ends of the nasal bones attach to cartilage that gives the lower two-thirds of the nose its shape.

Nasal Bone Anatomy

The topic of nasal bone anatomy is incredibly simple – these two, near-symmetrical bones are easy to locate – the top of the nose – and their external surfaces can be felt through the skin.

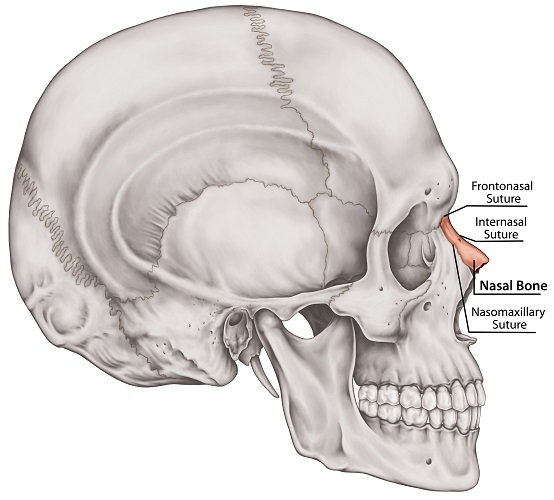

The top, narrow border (superior border) of either bone articulates with the frontal bone at the glabella (between the eyebrows). Where they meet is known as the frontonasal suture.

The outer, long border (lateral border) of the nasal bone meets the frontal process of the maxilla bone at the nasomaxillary suture.

The medial border articulates with the same border of its opposite nasal bone partner that sits on the other side of the nasal septum. This joining of twin bones is called the internasal suture.

Finally, the inferior border – the lower border – joins with the upper lateral nasal cartilage.

A distinction should be made between the nasal bone and inferior nasal concha bone, medial nasal concha, and superior nasal concha. These are very different structures. The nasal bone is the outer casing that lies just under the skin at the top of the nasal cavity. Nasal conchae are internal structures that increase the intranasal air volume so that air can be slightly warmed and humidified before reaching the lungs.

Unlike many other facial bones, nasal bones do not have a broad range of functions or anatomical structures. They are primarily structural.

A nasal bone x-ray shows this bone form but is not a good indicator of bone density or internal surface (posterior) shape. The uppermost part is thicker than the bottom; the inner wall is concave. How broad or high this tiny part of the facial skeleton is can make significant changes to one’s appearance.

Many people who are unhappy with how their nose looks pay for a surgical procedure called a rhinoplasty, where the entire form of the nose can be changed to provide a more (subjectively) pleasing silhouette. Even relatively novice surgeons can produce predictable results, although noses that do not have visible ‘humps’ are considered extremely hard to correct.

The nasal bones are covered by the proceris and nasalis muscles. The proceris muscle allows us to pull the middle of the forehead – the area between the eyebrows – downwards.

If you can flare your nostrils, you are using your nasalis muscles. Nostril dilation is enabled by the alar (outer nostril) part of the nasalis muscle or the dilator naris posterior. Closing the nostrils (such as when swimming underwater) uses the transverse part of the nasalis muscle (the compressor naris).

Both of these muscles are also important for a wide range of facial expressions – often negative ones – such as wrinkling the nose in disgust and frowning in anger. Botox injections administered by inadequately trained cosmetic surgeons can completely paralyse these muscles, leading to a lack of facial expression.

The inner groove of each nasal bone provides a space for the anterior ethmoidal nerve – a branch of the nasociliary nerve. Branches of the sensory anterior ethmoidal nerve innervate the skin of the sides of the nose, the septum, and the inner surfaces of the nasal cavity.

Nasal Bone Fracture

A nasal bone fracture is often the result of contact sports, motor vehicle accidents, and physical assault. Such fractures are common – up to 50% of facial bone fractures affect one – usually both – of these quite delicate bones. Nasal fractures are so common, the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems gives them their own category – ICD-10 Nasal Bone Fractures Diagnosis Code S02.2.

These fractures are common because the bones project outwards and are relatively thin. A closed nasal bone fracture will usually heal – without treatment – within three weeks; however, if the bones are misaligned, corrective surgery may be required.

In some cases, a little local anesthesia is enough to reset the bones using careful manipulation through the skin. This procedure is called manual realignment.

Fracture surgery – reduction surgery – is only required if there is a degree of nasal deformity. Any swelling must go down to observe the extent of nonalignment. If immediate breathing problems, nerve damage, or continuous bleeding are not a problem, an ENT surgeon or otorhinolaryngologist will usually wait for the swelling to recede before undertaking surgery.

If a nasal fracture is not fixed within seven to ten days, the healing process will begin and one or both nasal bones will need to be broken again during surgery.

Nasal Bone Spur

A nasal bone spur is a small projection of bone into the nasal cavity. This may or may not cause breathing problems, depending on its size and position. Nasal bone spurs can grow quite big over time or move towards structures like the septum and slowly push it out of place. This pressure can cause a lot of pain as the inner surface of the nasal cavity is very well innervated,. You only need to pull out a nose hair to know exactly how well!

It is more common for the cartilaginous nasal septum to develop spurs. Even so, these can affect nasal bone growth and cause malformation. Correction of a malformed nose is now performed endoscopically – via the nostril. This means any scars are hidden from view.

As a cosmetic operation, this can be an expensive procedure. However, if a spur causes continuous pain, an obstruction that affects breathing, abnormal nasal growth, or repositioning of other nasal structures, reparative surgery is usually covered by medical insurance.

Hypoplastic Nasal Bone

A hypoplastic nasal bone describes overly small bones that are usually detected long before birth. Measuring nasal bone size during ultrasound imaging can give clues about certain genetic disorders before undertaking a more invasive amniocentesis.

While very few fetuses (perhaps 1%) present with hypoplastic nasal bones in the second trimester, Down syndrome fetuses make up around 50% of this small group. Nasal bone hypoplasia is, therefore, a very strong morphological marker for trisomy 21.

Absent Nasal Bone

The absent nasal bone – always both bones – is a subcategory of the hypoplastic form. If absent at twelve weeks gestation, the fetus may have one of various genetic disorders.

As with hypoplasia, the most common of these is trisomy 21; however, there are also high-risk factors for trisomy 18 (Edward syndrome) and trisomy 13 (Patau syndrome). In rare cases, X-linked Turner syndrome may be indicated by absent nasal bones.

Quiz