Definition

The mandible is the largest bone in the human skull and supports the lower teeth. It is the only mobile bone of the skull and is essential for chewing, swallowing, and speaking. Many muscles originate at or insert into the mandible bone. This bone is comprised of a body and two rami, the shape and angles of which differ slightly between males and females.

Where is the Mandible Located?

Mandible location is at the bottom of the face, forming the lower jaw. It articulates with the left and right temporal bones to provide a broad range of motion – down and up, forward and backward, and side-to-side.

Mandible Anatomy

Mandible anatomy should be looked at in terms of movement, structure, and function. Even so, it is easiest to separate the mandible bone into two main parts – the body and the left and right rami.

Anatomy of the Mandibular Body

The mandibular body or body of the mandible bone is often described as horseshoe-shaped or U-shaped. You can feel its form by following the bony ridge from your chin to the corner of your lower jaw (called the mandibular angle or angle of mandible).

If you press the bone just under your chin you will feel an indentation. This is where both sides of the mandible body have fused (mandibular symphysis). To either side of this symphysis the bone is slightly raised to form two mental tubercles.

The two protruding tubercles travel diagonally toward the upper teeth, meeting higher up the mandibular symphysis to create a triangular shape.

This triangle is called the mental protuberance or mental trigone and gives the chin its shape.

To either side of the mental tubercles are the mental foramina – holes to the left and right of the mandibular body. These allow blood vessels and nerve branches to pass through. Both holes are situated about two centimeters below the corners of the lips.

Each foramen is edged by the lingula of the mandible or Spix spine on the inner surface of the mandible. Lingulae are bony outcrops onto which the jaw-supporting sphenomandibular ligaments attach.

The mandibular body also supports the lower teeth in an area of bone called the alveolar process of the mandible. Alveolar bone is comprised of two types – proper and supporting bone.

Alveolar bone proper forms the sockets of the teeth (alveoli) and is hard, cortical bone.

Supporting alveolar bone is primarily composed of cancellous or spongy bone.

At the back of the mandibular body (the interior surface) are several ridges and grooves. These provide attachment points for the paired mylohyoid muscle that runs from the mandible to the tongue bone (hyoid bone). This muscle is essential for the act of swallowing.

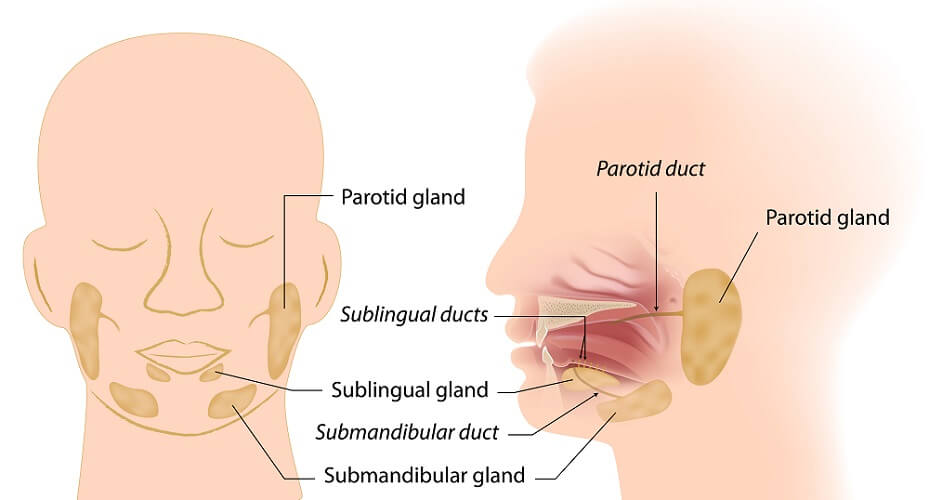

The submandibular fossa is an indentation just before the mandibular angle (corner of the jaw). It provides space for the left and right submandibular glands (see below). Indentations closer to the teeth partly surround the sublingual glands.

Under the chin, two side-by-side indentations form the digastric fossa. The anterior part of the digastric muscle helps us to open our mouths.

If you press under the middle of your chin and swallow, you will feel the deep-laying anterior belly of the digastric muscle tighten as it pulls the tongue bone up.

Ramus of the Mandible

The mandibular body ends at the mandibular angle (sometimes called the gonial angle) at the corner of the lower jaw. The rest of the mandible is called the ramus. We have one mandibular body and two rami.

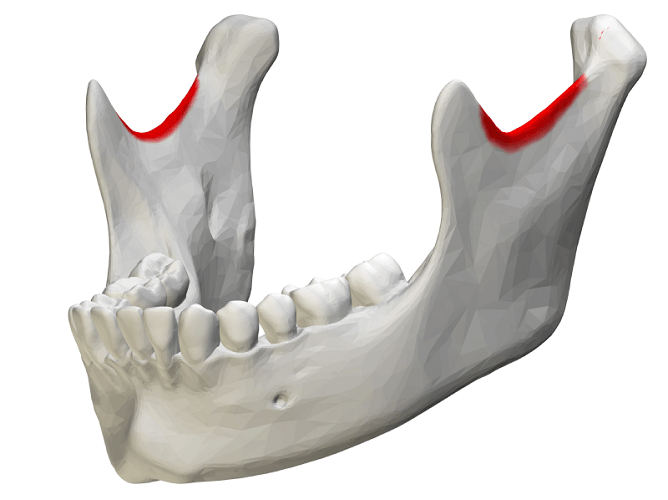

The rami provide articulation points by way of two processes – the coronoid and condyloid (or condylar) processes. More will be said about these later on.

The ramus of the mandible has two surfaces – lateral and medial. The lateral (external) surface is smooth and flat with a long ridge along the bottom. This ridge is an attachment point for the masseter muscle, important for chewing or mastication.

The medial (internal) surface of the ramus – like the body – also has a groove for the mylohyoid blood vessels and nerve, as well as an insertion point for the pterygoideus internus muscle. A list of mandibular muscles is given under a later heading.

Each ramus has four borders. The lower border of the ramus is thickest and follows the angle of the mandible.

The anterior (front) border runs up almost to where the coronoid process begins, and the posterior (back) border, covered by the parotid gland, nearly reaches the condyloid process.

The upper border is the place where the two mandibular processes project. This bone is thin. Between the two processes is a dip called the mandibular notch.

Processes of the Mandible

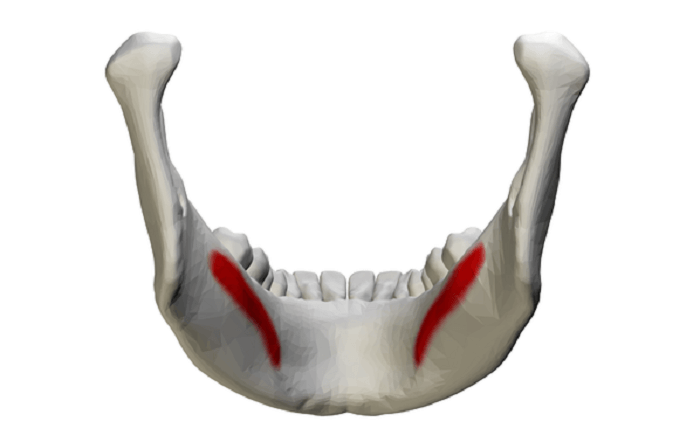

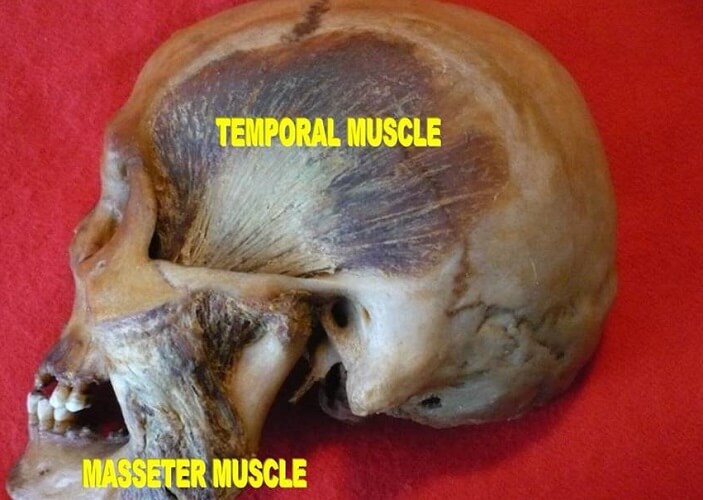

The coronoid process of the mandible (processus coronoideus) is a thin, flat piece of bone. This is where the temporalis and masseter muscles insert, as well as fibers from the buccinator muscle. These muscles play important roles in chewing, swallowing, and speech.

This process does not form a joint with another bone. The below computer-generated image shows a coronoid process fracture.

The condylar process of the mandible (processus condyloideus) is thicker than the coronoid process and split into two parts. At the top is the condyle; this is supported by the second structure, the neck. The condyle articulates within an indentation – the mandibular fossa of the temporal bone.

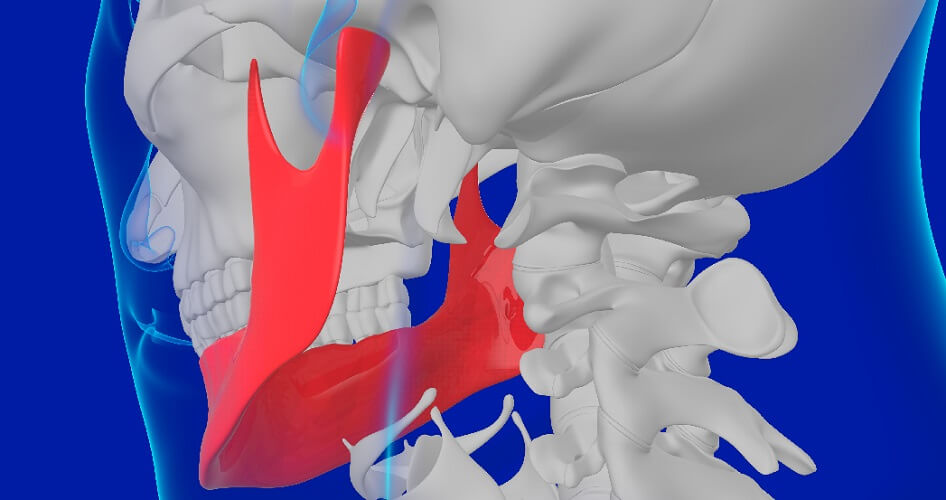

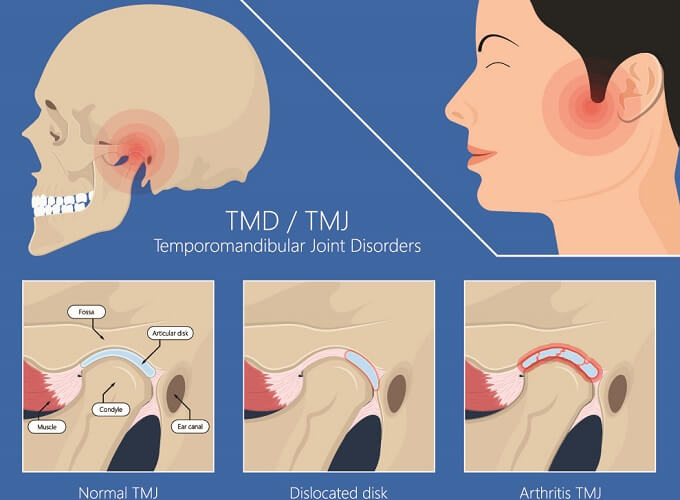

The mandibular fossa lies just under the zygomatic process of the temporal bone. The point of articulation is called the temporomandibular joint, often shortened to TMJ.

The temporomandibular joint is a bi-arthrodial hinge synovial joint. A hinged joint refers to a sliding joint, allowing the lower jaw to move forward and backward. If you jut out your chin, you are making good use of your TMJ.

The TMJ is composed of the convex head of the condyle and the concave indentation of the mandibular fossa of the temporal bone. A capsule or membrane surrounds the articular disc that separates both bones; each bone has its own synovial membrane.

Temporomandibular joint syndrome causes pain when chewing and often a clicking or popping sound when moving the lower jaw. Low range of movement and stiff muscles are also common symptoms.

Behind the articular disc, vascular and innervated tissue provides sensory and motor nerve messaging, nutrients, and oxygen. It is usually inflammation of this tissue that causes TMJ syndrome. Other causes are dislocated discs or arthritis.

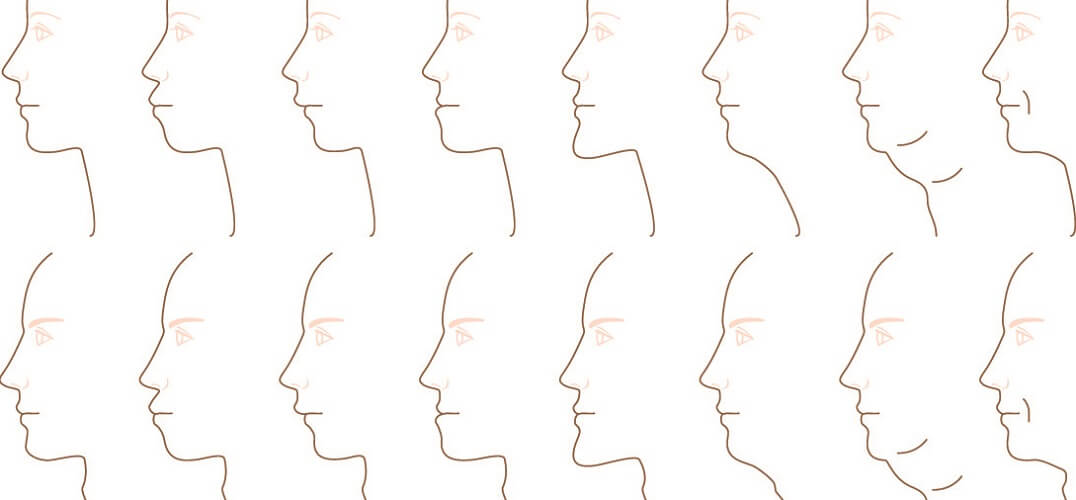

Mandible and Maxilla

The mandible and maxilla bone form the jaw but do not articulate with each other. Instead, they are connected by muscles and ligaments. Articulations between the mandible and maxilla bone are dental – in other words, only the teeth of the lower and upper jaw meet when the mouth is closed.

The painful trend of mandible piercing has led to countless infections and permanent damage to the salivary glands or branches of the facial nerve. Although piercings do not go through the mandible bone, their proximity to the mouth means a high risk of infection.

Without significant knowledge of anatomy, and with nerve pathways and anatomical landmarks differing from person to person, people performing mandible piercing procedures often damage important structures when they pass the curved needle up through the skin of the underside of the chin and into the oral cavity.

An untreated infection can spread to the bone of the mandible, causing mandibular necrosis.

Mandible Muscle Attachments

Both the mandibular body and the rami serve as attachment points for facial and cranial muscles. Most of these are masticatory muscles.

The outer (lateral) surface of the mandibular body hosts the following muscles:

- Buccinator – holds the cheek to the teeth, pushing food toward the teeth

- Mentalis – primary muscle of the lower lip (the ‘pouting’ muscle)

- Platysma – a large, thin sheet that runs from the lower jaw to below the collar bone. When you open your mouth in shock or surprise, the platysma pulls the lower jaw down

- Depressor anguli oris – pulls down the corners of the mouth

- Depressor labii inferioris – pulls down the bottom lip

The inner (medial) surface of the mandibular body provides attachment points for the:

- Mylohyoid – lifts the tongue bone, at the same time depressing (lowering) the mandible when we swallow

- Digastric (anterior belly) – like the mylohyoid, this muscle elevates the hyoid bone

- Genioglossus – one of a group of extrinsic tongue muscles that allows you to stick out your tongue and move it from side to side. It also pushes down the middle of the tongue when swallowing

- Geniohyoid – integral to swallowing, bringing the hyoid up and depressing the mandible

At the rami, the lateral pterygoid muscle inserts just below the condyle of the condyloid process; the temporalis muscle attaches to the coronoid process. The lateral pterygoid provides the force that pushes the mandible from side-to-side, down, and forward. The paired temporalis muscles control the temporomandibular joint.

All along the outside of the smooth outer surface of the rami runs the masseter muscle. This is one of the most important muscles of mastication and communication. It closes the jaw.

On the inner surfaces of the rami, close to the angle of the mandible, is an attachment point for the medial pterygoid muscle. This also lifts the mandible, closing the mouth.

Other functions of the medial pterygoid muscle are lower jaw rotation and protrusion (underbite).