Definition

The largest foramen (hole in bone tissue) in the body is the foramen magnum. It is part of the occipital bone at the skull base and surrounds several important central nervous system structures. It functions as an open gateway between the spinal cord and brainstem and is also the location of the joint between the skull base and the first cervical vertebra.

What is the Foramen Magnum?

In biology, a foramen is a hole or gap in a bone through which soft tissues can pass. While smaller foramina allow nerves and veins to cross through bone tissue, the foramen magnum is large enough to convey larger structures such as the medulla oblongata, brain membranes (meninges), blood vessels, nerves, and ligaments.

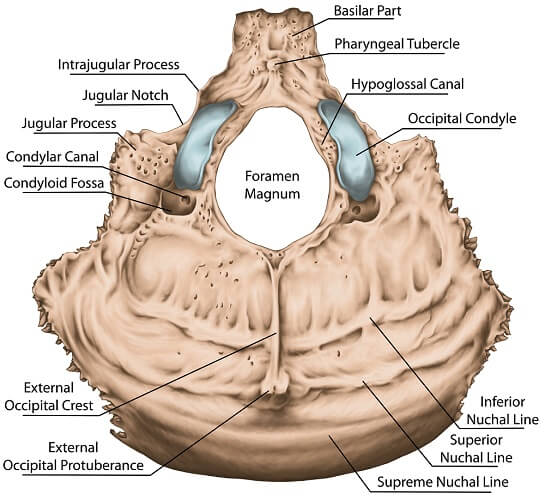

When we look at the inner and outer surfaces of the occipital bone, it is easy to see the largest foramen in the body. Smaller foramina of the skull base do not need to connect the brainstem to the spinal cord. To either side of the foramen magnum are the much smaller jugular foramina.

The foramen magnum basion is the inner edge of the outer rim that points toward the face. This basion is attached to the clivus, a bony incline that ends at the dorsum sellae of the sphenoid bone. The foramen magnum opisthion is at the opposite edge, facing the back of the head.

Looking at the outer surface of the foramen magnum (below), we immediately notice the gray ridges that form the left and right occipital condyles. These are rounded structures that form an articulation point with the first vertebra (C1), also called the atlas. The joint is, therefore, called the atlanto-occipital joint. Unlike other vertebrae, this joint does not feature an intervertebral disc; instead, it is lined with cartilage to allow smooth motion. Together with the ligaments of the neck, this joint allows us to flex the neck (nod).

Where is the Foramen Magnum Located?

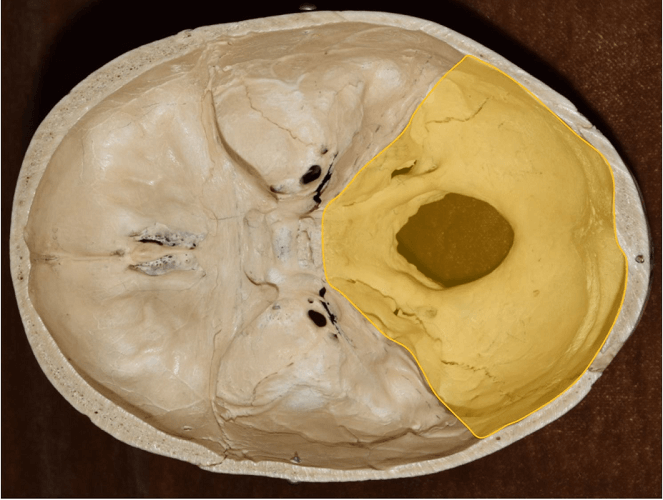

The foramen magnum is located between the basilar part (base) of the occipital bone, the occipital condyles, and the squamous part of the occipital bone. At the squamous part, the occipital crest forms a ridge that runs from the inner surface of the back of the skull and widens into a raised posterior edge that circles part of the foramen magnum.

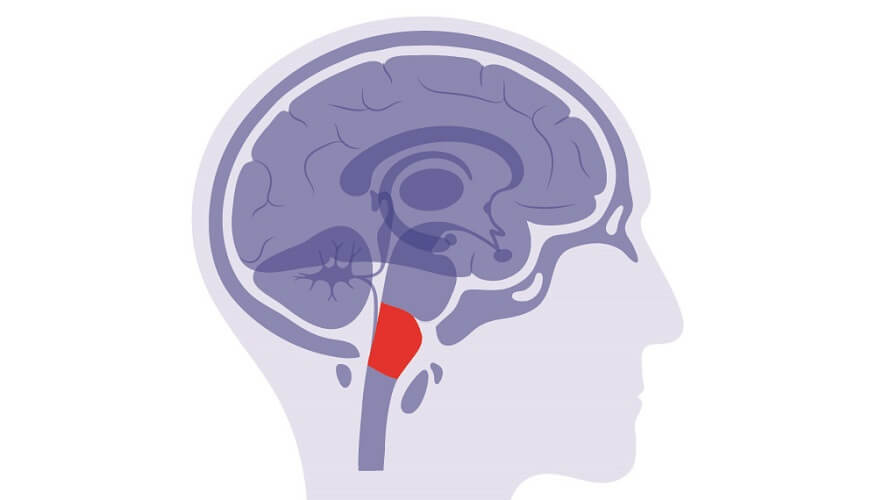

This location is also described as the inferior part of the posterior cranial fossa – a dip in the internal surface of the skull that provides space for the brainstem and cerebellum.

It is not possible to feel the position of the foramen magnum as it is protected by the muscles of the upper neck. This is for a very good reason – the important structures it protects are extremely fragile. A foramen magnum fracture can cause paralysis or death and is most commonly associated with motorcycle accidents.

What Passes Through the Foramen Magnum?

Many essential and delicate structures pass through the foramen magnum:

- Medulla oblongata: central to autonomic central nervous system functions such as the heart rate and breathing, as well as connecting nerve pathways between the spinal cord and brain. The place where the medulla oblongata is contained within the foramen magnum is called the cervicomedullary junction.

- Meninges: three connected membranes that protect the brain, brainstem, and spinal cord, produce and allow the flow of cerebrospinal fluid, and provide a source of oxygen and nutrients thanks to an extensive network of blood vessels.

- Spinal root of the accessory nerve: this nerve is responsible for neck movement via innervation of the trapezius and sternomastoid muscles. A nerve root is the first, thicker part of a nerve. The accessory nerve is the eleventh cranial nerve (CN XI).

- Cranial nerves: cranial nerves IX and X also pass through the foramen magnum. The ninth cranial nerve is the glossopharyngeal nerve that begins at the medulla oblongata; the tenth cranial nerve is the vagus nerve – probably the most broadly functioning cranial nerve.

- Cerebellar tonsils: protuberances of the underside of the cerebellum that are part of the structure that coordinates muscle movement and tone. With tonsil malformation, these can elongate and push through the foramen magnum, blocking cerebrospinal fluid flow. A sudden build-up of pressure in the brain due to such a blockage can be fatal unless quickly treated.

- Inferior vermis: another part of the cerebellum that partially enters the foramen magnum is the bottom portion of the cerebellar vermis; vermis is ‘worm’ in Latin. This part of the brain is essential for eye movement and limb coordination.

- Fourth ventricle: the fourth ventricle is part of the ventricular system of the brain – a cerebrospinal fluid production and drainage system that adds a shock-absorbing protective wall around the delicate central nervous system.

- Vertebral arteries: the vertebral arteries (two vertebral arteries and one basilar artery) branch upwards from the subclavian artery and enter the neck, protected by the transverse canal of the vertebrae. They supply approximately 20% of the brain’s blood supply. The vertebral arteries are most likely to undergo compression close to where they pass through the foramen magnum.

- Anterior and posterior spinal arteries: spinal arteries are further branches of the vertebral arteries and supply blood to the spinal cord. The anterior spinal artery feeds the anterior portion; the posterior spinal artery, the posterior portion. Both join at the foramen magnum.

- Tectorial membrane: the tectorial membrane is the continuation of a ligament called the posterior longitudinal ligament. This membrane connects the axis (the second cervical joint) to the clivus, meaning it must pass through the foramen magnum. Although damage to the tectorial membrane is rare, it is sometimes seen in pediatric head and neck injuries, usually as a result of motor vehicle accidents. These can cause the tectorial membrane to stretch or tear making the joints between the occipital bone and first cervical vertebra and first and second cervical vertebrae less stable.

- Alar ligaments: the alar ligaments connect the occipital condyles on the outer edge of the foramen magnum to the second cervical vertebra. They stabilize the neck at the first and second cervical vertebra when rotating the head and stop us from flexing and rotating the head too far. Once again, the primary cause of alar ligament injury is a motor vehicle accident.

Foramen Magnum Syndrome

Foramen magnum syndrome describes a range of symptoms that coincide with pressure within the foramen magnum, most commonly due to a tumor. Early symptoms include a headache situated at the back of the head that becomes worse when moving the neck, sneezing, or coughing. As pressure increases, the connection between the brain and spinal cord is disrupted. This leads to sensory deficits in the form of pins and needles, pain, weakness, and paralysis, and motor deficits where the connection between brain and muscle is affected.

As increased pressure is most commonly at one side of the foramen magnum, these deficits are often unilateral (on one side of the body). Autonomic functions also need to pass through from brain to body, so breathing difficulties and heart-rate abnormalities are also known to occur. These are relatively late symptoms.

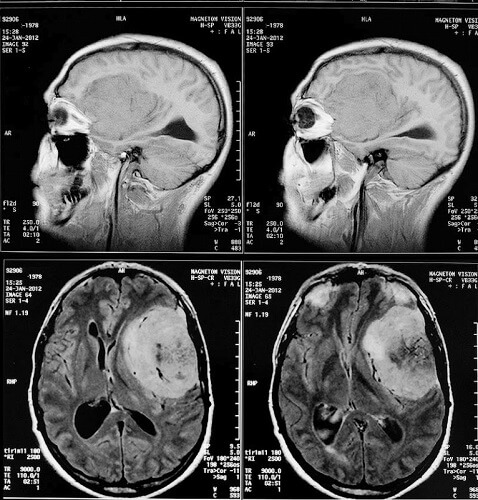

One cause of this syndrome is a foramen magnum meningioma that can develop above, below, or on either side of the vertebral arteries. As the name suggests, this is a tumor of the meninges – the membranes that feed and protect the brain. In the below computer tomography (CT) image, you can see how the darker mass in the top two pictures is pushing on the underlying structures. The actual form of the meningioma is easier to see in the lower two images.

It is possible to remove these tumors and neurosurgeons use various routes to reach them:

- Transsphenoidal: through the nose and sphenoid bone

- Transoral: through the mouth and up into the palate (palatine bones)

- Transcochlear: through the ear and down

- Suboccipital: through the basilar part of the occipital bone

- Transcranial: through and along the frontal bone

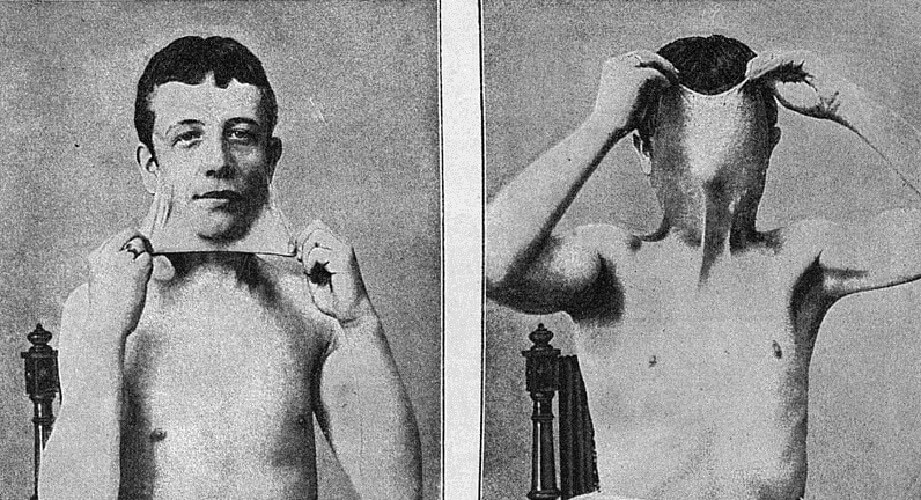

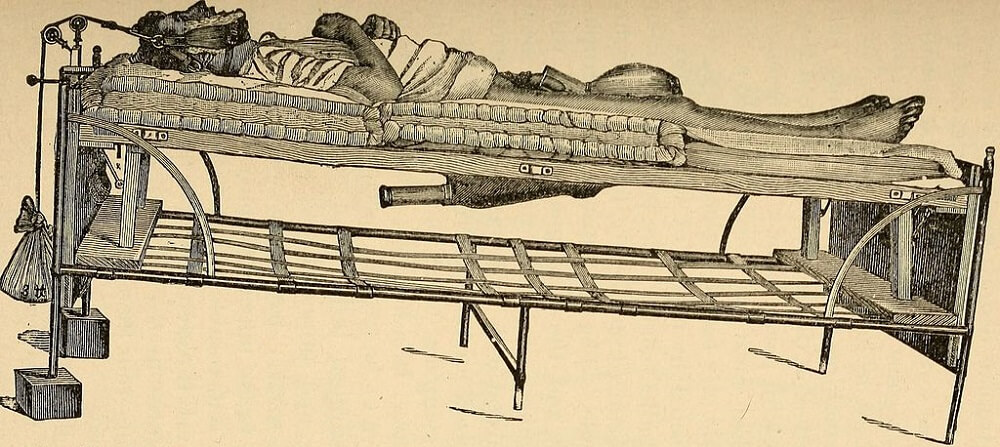

Another cause of foramen magnum syndrome is neck vertebrae dislocation involving the upper two cervical vertebrae. Symptoms tend to be acute and the later signs described earlier in this section can appear immediately. Treatment is usually fixation, although surgery is possible with modern techniques. This was not the case in the earlier part of this century and treatment was basic, as we can see in the below image.

Acquired or congenital non-genetic causes of foramen magnum syndrome are often due to malformations in one of the structures that pass through it, such as a type I Chiari malformation (CMI) where, as previously mentioned, the cerebellar tonsils become elongated. This report describes many of the early symptoms. Surgical treatment for a Chiari malformation or any causes of increased pressure in this gateway between the brain and spinal cord is called foramen magnum decompression.

Finally, foramen magnum hypoplasia or ‘little foramen magnum’ involves an abnormal narrowing of this gap and subsequent pressure on the structures that pass through it. Genetic disorders such as achondroplasia (dwarfism) and cutis laxa (see below image) are associated with congenital foramen magnum stenosis.