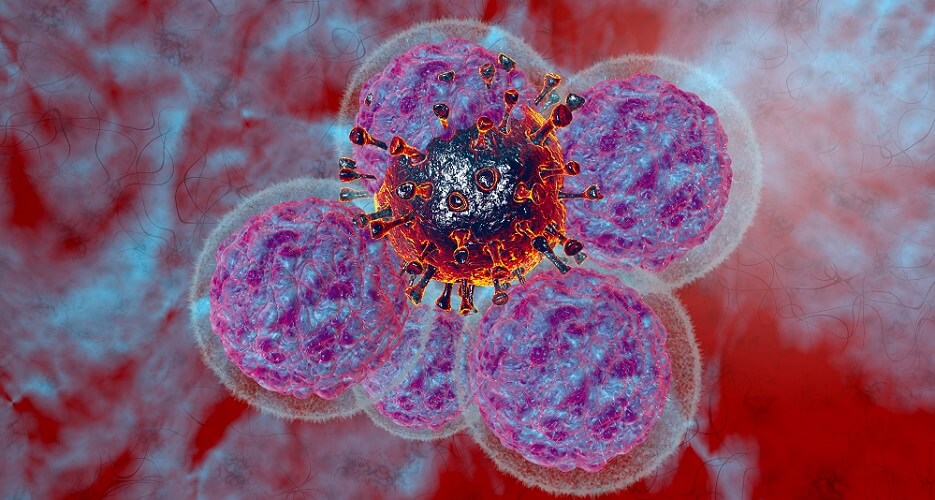

Definition

The white blood cell or leukocyte is an immune cell that protects the body from endotoxins, invading pollutants, bacteria, and viruses; this broad group of cells also removes dead or damaged cells. White blood cells are split into two main groups – granular and non-granular. Granular white blood cells are basophils, eosinophils, and neutrophils. Non-granular leukocytes are lymphocytes and monocytes.

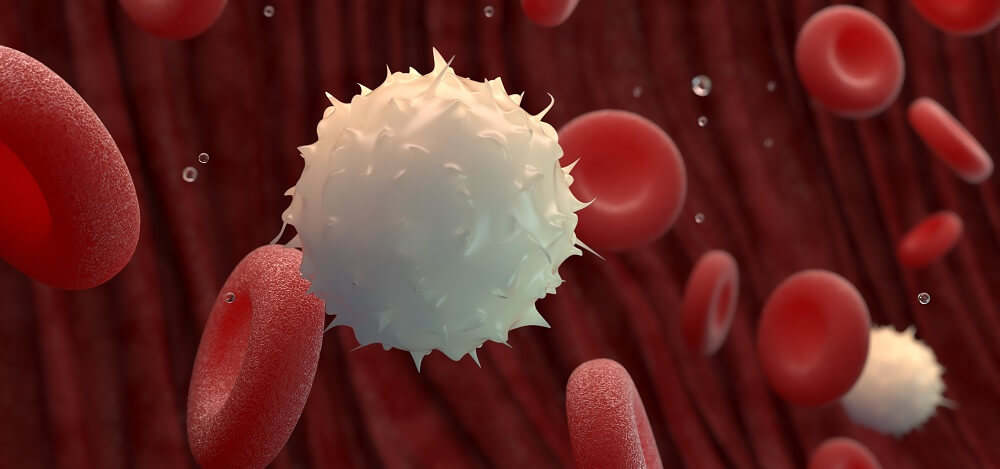

White Blood Cell Structure

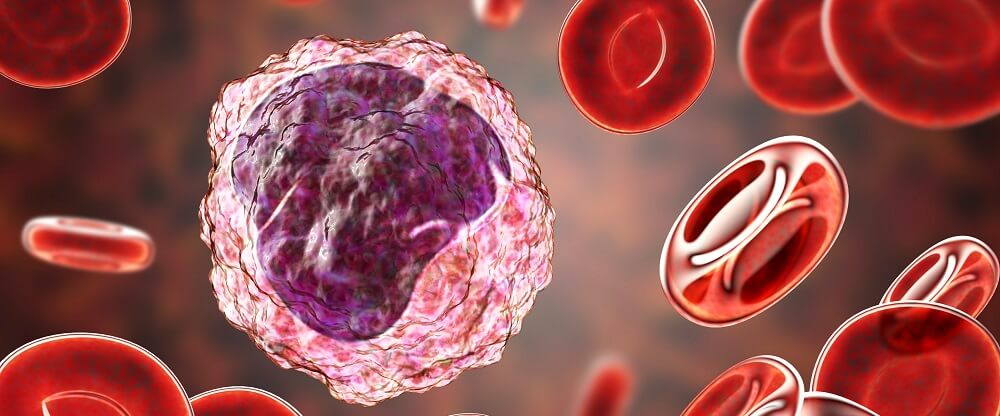

White blood cell structure depends on the type of cell. While all contain a nucleolus contained within a nucleus, mitochondria, Golgi apparatus, phospholipid membrane, centrioles, rough and smooth endoplasmic reticulum, ribosomes, lysosomes (aspecific granules), and peroxisomes, white blood cell function, shape, size, and signaling capacities differ.

White blood cells (WBCs) have an incredible communication capacity. They signal to and receive signals from other cells, locate abnormal proteins in all types of tissue, and bind to cell and pathogen membranes. This requires a complex range of receptors and channels on and in the white blood cell membrane.

Granulocytes

The body contains five types of granulocytes – these are white blood cells that contain cell-specific granules.

Neutrophils are between twelve to fifteen micrometers in diameter and have multi-lobed nuclei. Neutrophils move via diapedesis and only live for a few days.

Eosinophils have two nucleus lobes and large granules. These are rounded cells of around fifteen micrometers in diameter.

Basophils are the same size as neutrophils and have either double-lobed or S-shaped nuclei.

Mast cells are oval or round and only found in blood in their immature form. They mature in other tissues.

Natural killer (NK) cells are large, granular lymphocytes that mature in the lymphoid organs. These can self-renew.

Agranulocytes

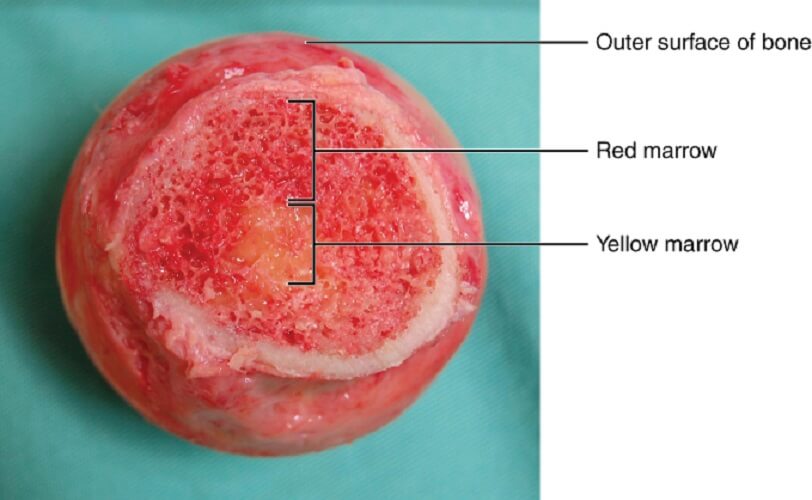

Agranulocyte white blood cells do not contain cell-specific granules and are categorized into two main groups – lymphocytes (T cells and B cells) and monocytes. Unlike the other white blood cell types, lymphocytes are not produced in the bone marrow but in the lymphatic tissues; however, their precursor cells are manufactured in red bone marrow.

Monocytes are grouped into three main types named according to their vital cell membrane protein markers: classical, intermediate, and non-classical monocytes. Monocytes can differentiate into macrophages or dendritic cells.

Hematopoieitic Precursor Cells – An Outdated View

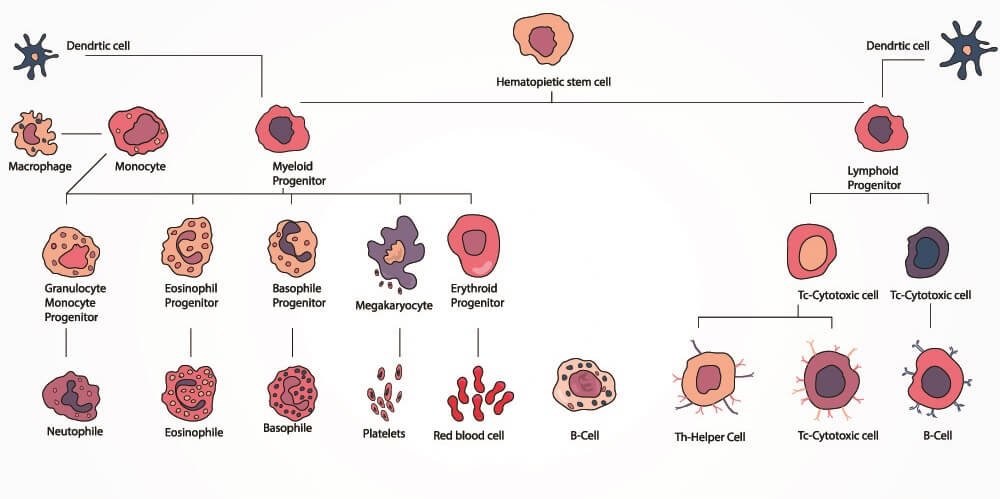

Every cell in the blood – red blood cell, thrombocyte, and white blood cell – is the result of various stages of differentiation from a single multipotent hematopoietic stem cell or hemocytoblast.

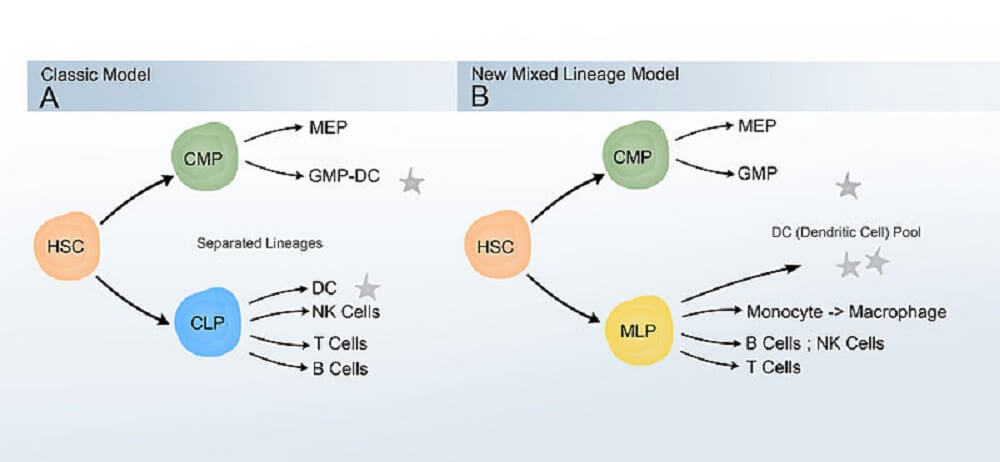

Classical White Blood Cell Lineage

Hematopoietic stem cells differentiate into one of two progenitor cell groups – the common myeloid progenitor that produces granulocytes and monocytes, and the common lymphoid progenitor that differentiates into lymphocytes.

The common lymphoid progenitor produces either natural killer cells (granular lymphocytes) or small lymphocytes. These are lymphoid leukocytes, so called because they differentiate and mature in the lymph organs. Small lymphocytes become T or B cells. B cells can further differentiate into plasma cells.

The common myeloid progenitor is responsible for the production of all other blood cell types – erythrocytes, thrombocytes, and myeloid leukocytes. The first round of progenitor white blood cell differentiation leads to mast cells and myeloblasts. A myeloblast can further differentiate into one of four white blood cell types – basophils, neutrophils, eosinophils, and monocytes. Monocytes differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells.

Recent Research into Leukocyte Differentiation

This classical view, however, is rapidly becoming outdated. The differentiation roadmap described above is still taught in schools but this is bound to change in coming years.

Previous studies into where blood cells come from based results on what is now an overly simple technology. Mice would be irradiated to halt the blood cell producing capacity of the bone marrow and new bone marrow was transplanted.

This transplantation and colonization method gave rise to the idea that hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) can both self-renew and differentiate into other blood cells, and progenitor cells cannot self-renew and only differentiate into very limited cell types. This no longer seems to be the case.

In particular, research into the dendritic cell has complicated matters. We now know that lymphoid and myeloid progenitors cross over. Rather than producing either myeloid or lymphoid cells, they are more likely to be biased to one form but play roles in blood cell formation in the other group.

White Blood Cell Types and Functions

We have already looked at white blood cell morphology and been introduced to the basic types. This section looks at their functions.

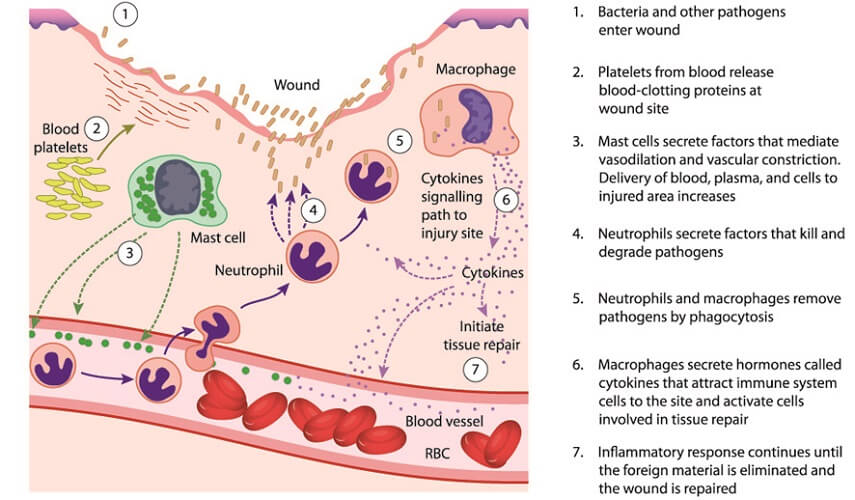

How these cells locate pathogens and damaged cells depends on the interaction of cell membrane proteins and chemical signaling molecules called cytokines.

Gene expression of membrane proteins and cytokine production differs between white blood cell types and gives them their more specific functions within the immune system.

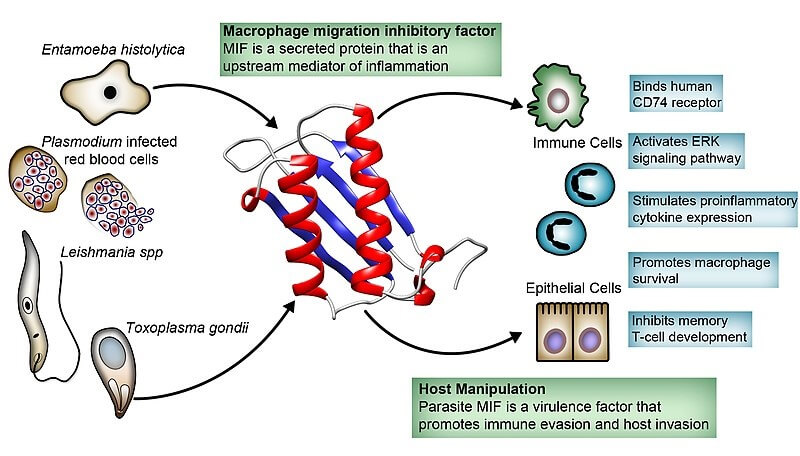

Leukocytes migrate to areas of infection and injury when circulating antigen-presenting cells (APCs) – some types of white blood cells – recognize abnormal surface membrane molecular patterns. Damage-associated molecular patterns, microbe-associated molecular patterns, and lifestyle-associated molecular patterns are called DAMPs, MAMPs, and LAMPs respectively.

Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) are white blood cells. Professional APCs like dendritic cells, macrophages, and B cells recognize a foreign antigen (cell membrane protein), internalize that cell, and construct protein markers on their own membranes called MHCs.

APCs use these MHCs to activate other WBCs to attack any membrane that contains that specific foreign antigen.

Non-professional APCs produce a different form of MHC upon contact with an antigen. This group is not restricted to white blood cells. Any cell with a nucleus can be a non-professional antigen-presenting cell.

Another functional group of WBCs is the phagocyte. Professional phagocytes are monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and eosinophils. Nonprofessional phagocytes are not white blood cells and do not ingest microorganisms. Instead, they perform phagocytosis on dead cells.

Again, membrane surface proteins are essential for the recognition of undesired molecular patterns; APC and phagocytic groups overlap.

Neutrophil Function

Neutrophils carry out the body’s initial immune response to bacteria. They are both antigen-presenting cells and phagocytes. The blood and other tissues contain high numbers of neutrophils and these relocate to areas of infection.

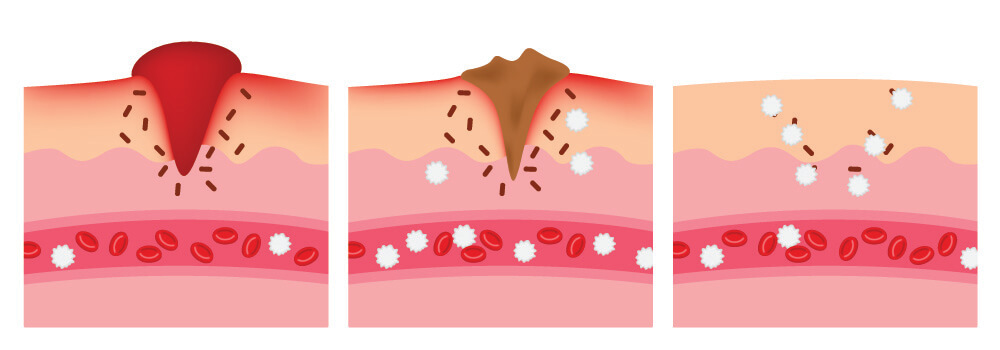

A chain of blood cell-associated events causes the symptoms of infection – rubor (redness through vasodilation), calor (heat through increased energy expenditure), dolor (pain through pressure on sensory nerves), and tumor (swelling through increased living and dead cell mass and fluids like blood and pus).

Once threatening antigens are recognized by neutrophil membrane receptors, the cell engulfs, internalizes, and digests the undesired particle.

Neutrophil aging occurs over 24 hours and is a type of differentiation that gives these cells more specific functions. For example, in the presence of cancer, neutrophils may change which genes they express and eventually stop responding to mutated cells.

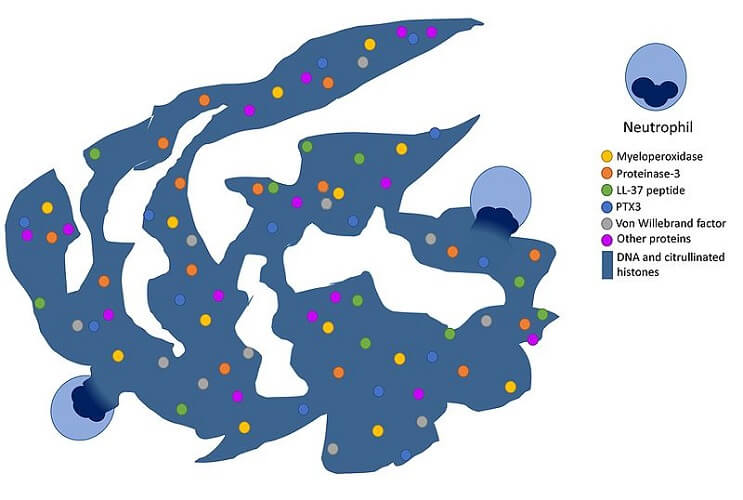

One specific function is the ability of a neutrophil white blood cell to form neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). They produce specific proteins that help them break down chromatin to construct sticky external webs that contain bacteriocidal chemicals. Suicidal NETosis and vital (or classical) NETosis are forms of programmed cell death. Inflammatory illnesses like diabetes increase the number of neutrophils that carry out NETosis.

The more we learn about neutrophils, the wider their range of functions. This seems to be the case with all white blood cells.

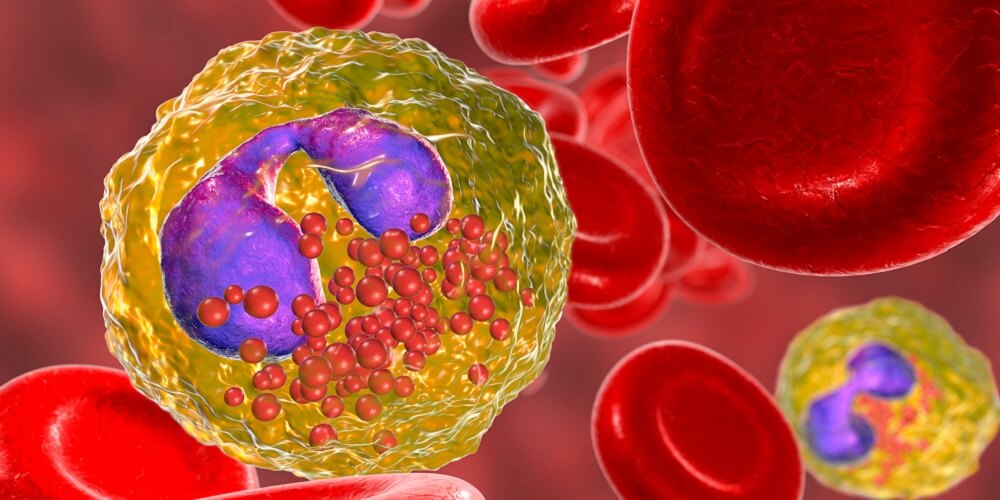

Basophil Function

Basophils have similar functions to mast cells. These two cell types work together, even though basophils only make up around one percent of all white blood cells in the blood and tissues. They have always been associated with parasitic, inflammatory, and allergic immune responses.

Basophils are not APCs as they do not express the genes for MHC construction, but they can take up these molecules from dendritic cells during a process called trogocytosis.

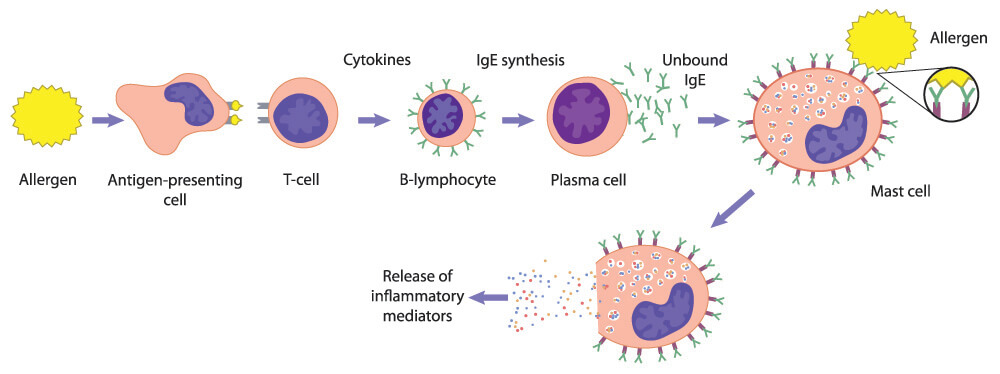

Basophils are also not phagocytes. Their main role is to produce chemicals that help the immune response. When their immunoglobulin E (IgE) proteins bind to antigens, the cell releases the contents of its granules into the extracellular space. These consist of substances such as histamines that play important roles in the leukocyte adhesion cascade.

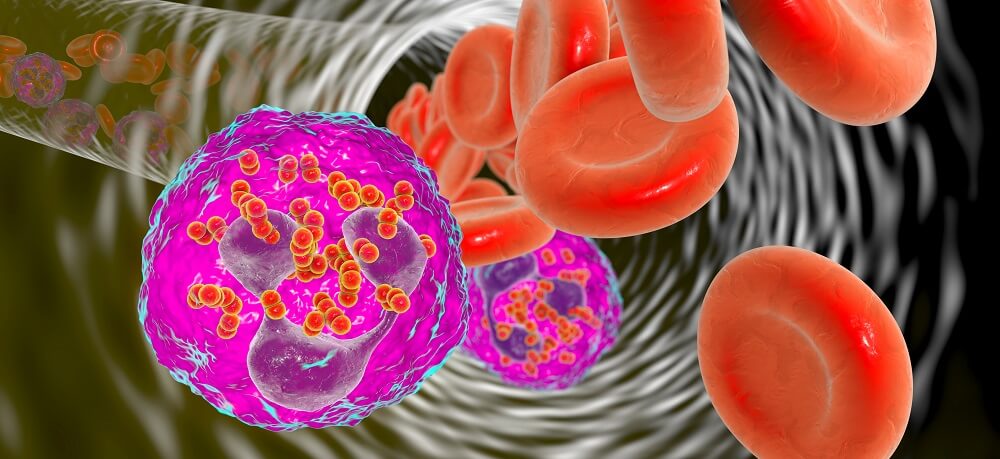

Eosinophil Function

Eosinophils are granulocytic white blood cells that make up 1 to 4% of leukocyte populations at normal levels. They are mainly involved in chronic inflammation, allergic reactions, and parasitic infections – similar to the function of basophils.

Eosinophils release granules that destroy parasites, can decompose histamines and so regulate an allergic response, increase of decrease B cell and plasma cell production, and also act as APCs in the presence of dendritic cells.

It used to be thought that eosinophils were phagocytes but it now seems they release mitochondrial DNA to form traps as well as produce cytotoxic proteins and cytokines.

Some recognize viral PAMPs; others contribute to mucus production in the gut and airway. They are a key factor in asthma pathology. Another important eosinophil function is the repair of damaged tissue through the release of growth factors, even in the brain. This effect must be carefully regulated by as yet unknown factors because high levels of eosinophils can slow down the healing process.

It now seems that eosinophils might even play a role in glucose homeostasis. Without the presence of eosinophils in adipose fat, mice become obese and develop insulin resistance and glucose intolerance.

Mast Cell Function

Mast cells are located primarily in connective tissue. These granulocytes store cytokines, inflammatory response modulating chemicals such as histamine and heparin, prostaglandins that reduce an allergic response, and enzymes. Different enzymes cause different effects, from increased gut peristalsis to blood vessel relaxation.

Natural Killer Cell Function

The fact that natural killer cell deficiency leads to high susceptibility to viral infections shows how important these first-line white blood cells are. Furthermore, the lower the levels of NK cells the higher the risk of developing cancer.

Known to target cancer cell antigens and cells infected with viruses, these lymphoid white blood cells are being used to treat both.

A natural killer (NK) cell uses receptors to detect the absence of self-antigens. Self antigens are marking proteins of the membranes of the body’s own cells that can initiate an immune response.

While foreign cells show molecular patterns of a particular class (class II), own cells have patterns that tell the body they are natural (class I).

Natural killer cells have receptors for MHCI expressing cells; when these patterns are absent – such as with virally-infected or cancer cells – the NK cell will destroy it via the release of cytotoxic granules. Natural killer cells do not need to be activated by an APC to work.

Dendritic Cell Function

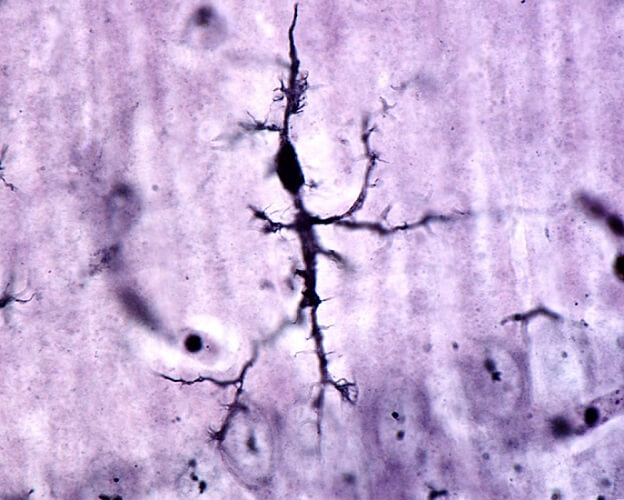

Dendritic cells are important antigen-presenting cells that communicate with a broad range of cell types. They can cross the blood-brain barrier and enter every tissue where they recognize MHCI and MHCII proteins, internalize the carrying cell or particle, and bring it to a T cell or B cell.

Cytokine release to bring other white blood cells into an area of infected or damaged cells is also a dendritic cell function.

While dendritic cells are not phagocytes, they are known to ‘nibble’ cells, removing and digesting part of the membrane and so killing the cell.

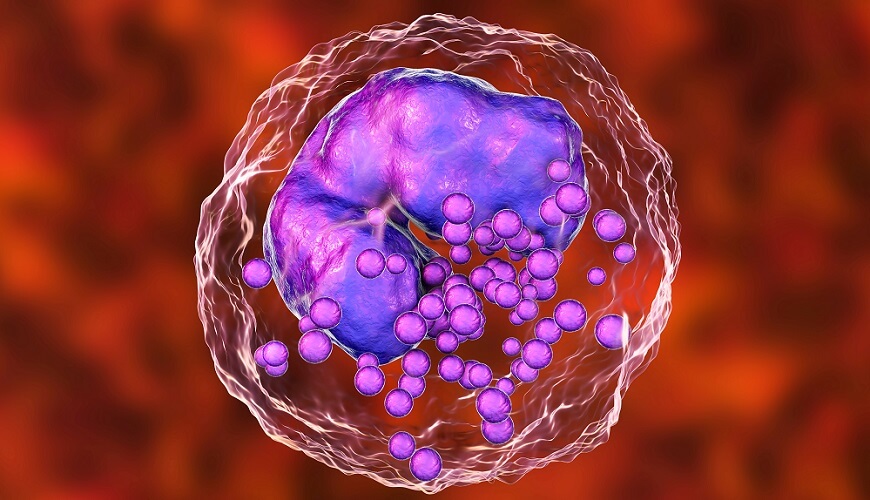

Monocyte Function

Monocytes are phagocytes and antigen-presenting cells that constitute around five percent of white blood cells in the bloodstream. They can differentiate into dendritic cells, macrophages, histiocytes, microglia cells, osteoclasts, and mesangial cells, but as monocytes have their own set of functions.

Monocytes patrol the body looking for damaged cells and pathogens. They infiltrate infected areas to secrete regenerating growth factors and cytokines to call more immune cells to the region.

Monocytes are divided into three subsets – classical, intermediate, and non-classical – depending on the receptors they express. Each type functions differently, although the great majority are classical monocytes. These operate as phagocytes.

Intermediate monocytes are antigen-presenting cells that also stimulate T cell production, help renew damaged blood vessels, and take part in the inflammatory response.

Non-classical monocytes search for signs of cellular damage and bring information to T cells as APCs. Known as pro-inflammatory cells, non-classical cells secrete inflammatory cytokines when they find infected cells.

Small Lymphocyte Function

Small lymphocytes are T and B cells. The other lymphocyte type – the natural killer cell – is much larger.

T and B cells most often require activation by APCs, although some B cells can self-activate. T cells either attack directly as cytotoxic T cells or activate B cells as helper T cells. Without contact with an antigen-presenting cell, a T cell can neither differentiate nor activate.

B cells make antibodies for the undesired antigens coupled to the MHCs that activate helper T cells. Antibodies (immunoglobulins) circulate the body and attach to any cell with membrane markers that match the antigen of the original infected cell.

White Blood Cell Count Range

A white blood cell count range looks at any of the above-described cell types to detect signs of infection or tissue damage. Newborns typically have very high WBC counts and healthy children under two present with elevated white blood cell count results.

In adults, the following applies:

- Normal white blood cell count: 4,500 – 10,500 WBC/microliter

- Elevated white blood cell count: over 11,000 WBC/microliter

- Low white blood cell count: under 4,000 WBC/microliter

High white blood cell count causes include the presence of infection, tissue necrosis, tissue inflammation (acute or chronic), stress, immune system disorders, lifestyle factors such as smoking and being sedentary, and cancer.

Low white blood cell count causes also include cancer, bone marrow deficiencies, and immune system disorders. They may also be low due to nutritional imbalances, chemotherapy and radiation treatments, autoimmune disorders, and some infections.