Definition

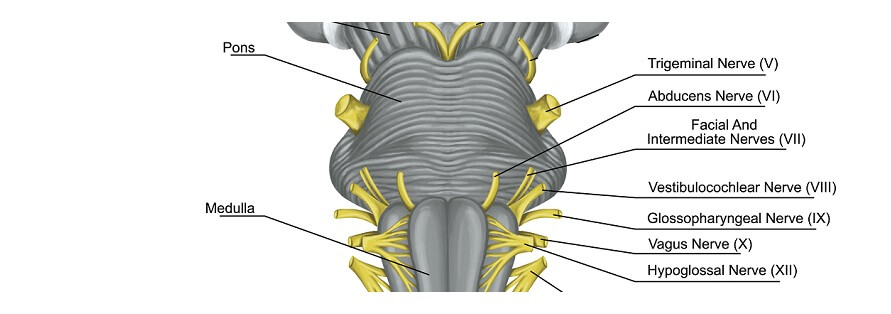

The facial nerve (CN VII) is one of the most complex of the cranial nerves. It is a paired (left and right) mixed nerve, divided into parts according to its location (intracranial, intratemporal, and extratemporal). CN VII splits into branches that control multiple facial muscles, salivary and tear glands, and some sensory surfaces of the tongue.

Facial Nerve Anatomy

Facial nerve anatomy is complicated; it is a mixed cranial nerve (CN VII) with multiple functions. Most textbooks look at this cranial nerve in sections – intracranial, intratemporal (within the temporal bone), and extracranial.

Intracranial

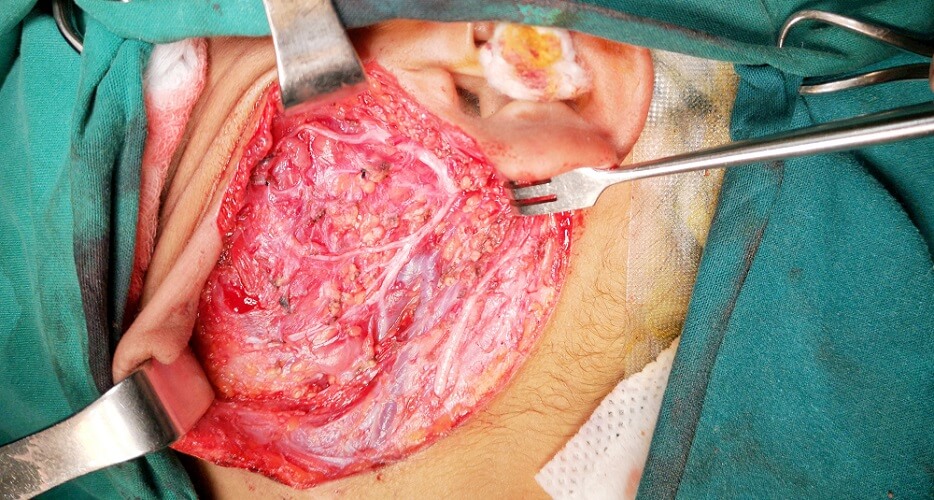

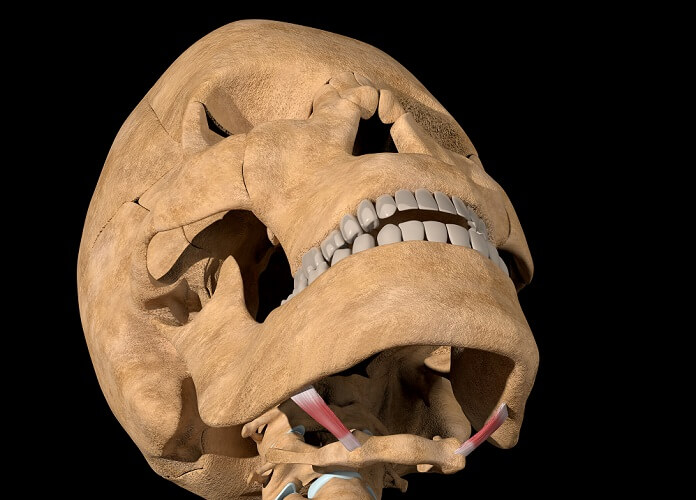

The intracranial facial nerve begins at the brainstem. It is a combination of neurons that derive from two roots – a motor root and a sensory (and parasympathetic) root. The fibers in these roots fuse to form the paired CN VII nerve. We have two – right and left. In the image you can see how this nerve is split into two separate roots.

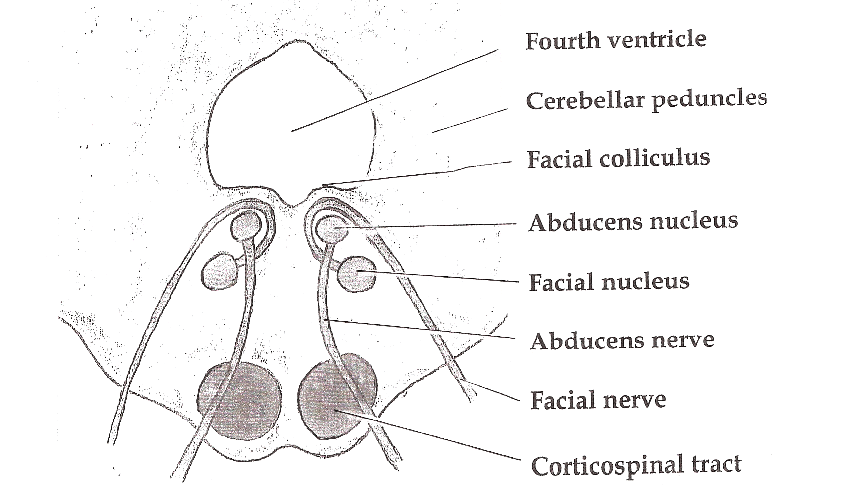

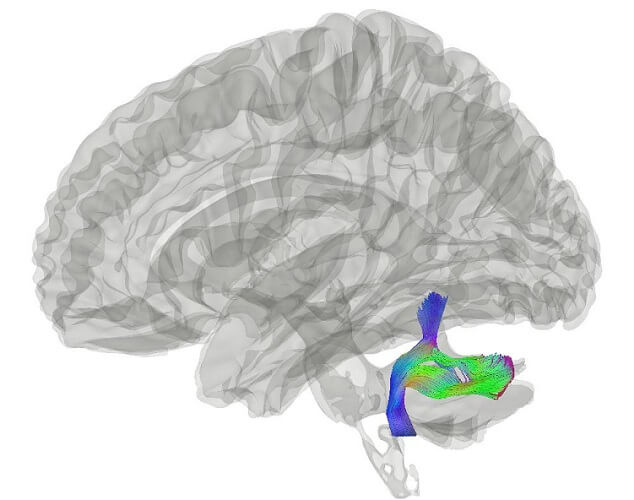

The motor root (or motor part) is thicker than the intermediate (or sensory) root. It is directly connected to upper motor neurons that runs from the primary motor cortex of the frontal lobe of the brain. The upper motor neurons arrive at a collection of neurons called the facial nucleus.

The facial nucleus has a dorsal (back) and a ventral (front) part. This is important for when we look at facial nerve damage later on.

The dorsal side of the facial nucleus receives information from both brain hemispheres. The dorsal side is connected to the top of the face – so both hemispheres control facial expression in the upper face.

The ventral sides control the bottom half of the face; the left ventral part of the facial nucleus receives information from the right hemisphere and vice versa.

It is from the facial nucleus that the motor root emerges. Motor fibers travel through the pons and emerge at a point between the olive and the inferior peduncle.

The sensory root culminates at the medulla oblongata. It is important not to forget that efferent motor pathways travel from the central nervous system to muscle fibers; afferent sensory pathways travel from the sensory organs to the central nervous system.

Do you have trouble remembering which is efferent and which is afferent? They are the SAME (or rather, Sensory Afferent, Motor Efferent).

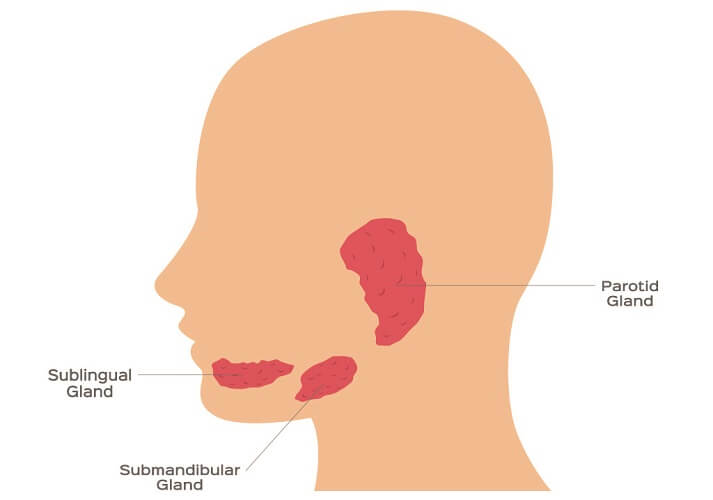

The sensory root of the facial nerve brings descending parasympathetic fibers from a salivary gland control center in the brainstem (the salivatory nuclei) to the salivary glands. This root is also composed of ascending sensory fibers that bring information back to the brainstem. Although CN VII runs through the parotid gland, it does not innervate it.

The motor and sensory sections that lie inside this part of the skull are referred to as the intracranial part of the facial nerve.

Intratemporal

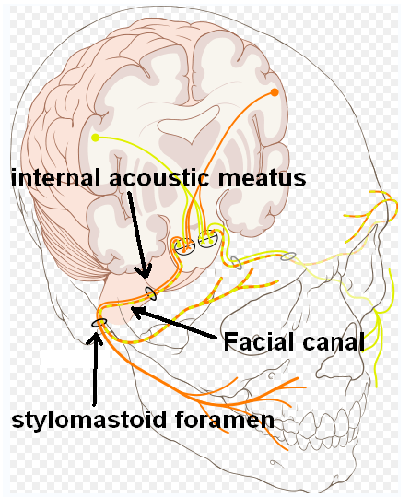

The facial nerve exits the intracranial segment through the internal auditory meatus of the temporal bone. It runs along a groove along the inside of the temporal bone called the facial canal.

Until this mixed nerve passes through the stylomastoid foramen, it is referred to as the infratemporal part of the facial nerve.

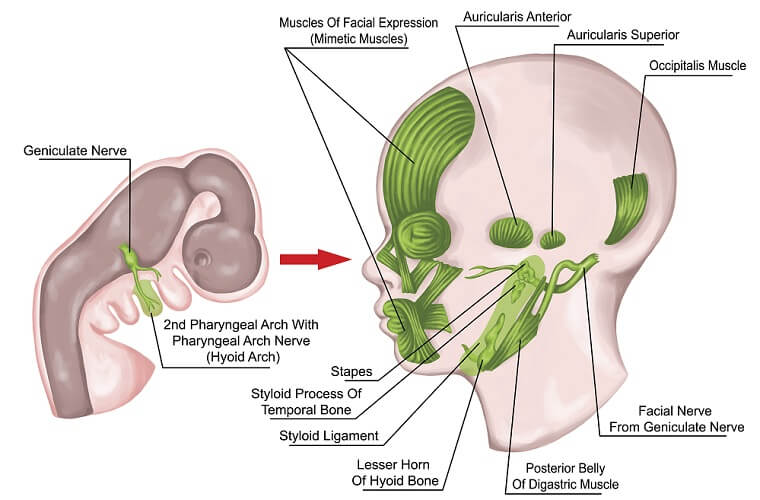

Once through the internal auditory meatus, the bodies (somas) of the sensory neurons of the facial nerve group to form the geniculate ganglion. A ganglion is a group of cell bodies that have their axons in peripheral tissues and detect special sensory signals such as taste, touch, smell, and sound.

Past the geniculate ganglion, parasympathetic fibers of the facial nerve split to produce the first facial nerve branch – the greater petrosal nerve. A list of facial nerve branches and their functions will be found further on.

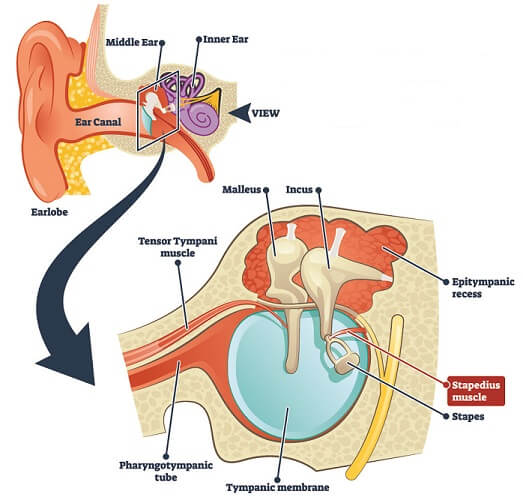

The second branch is a group of motor fibers that innervate the stapedius muscle.

The third and final branch at the intratemporal part is the chorda tympani. This is the last time that sensory nerves in the facial nerve come to play. After the chorda tympani, all branches have motor effects.

The facial nerve now exits the cranium at the stylomastoid foramen.

Extracranial

The extracranial facial nerve lies outside of the skull. As all extracranial branches are motor nerves, this part is often (confusingly) referred to as the motor root. The below image shows where these CN VII branches run.

The extracranial facial nerve branches after the stylomastoid foramen are:

- Posterior auricular nerve

- Nerve to the digastric muscle

- Nerve to the stylohyoid muscle

After this point, the motor root of the facial nerve enters the parotid gland but does not innervate it. Within the gland, the final five branches spread through the face:

- Temporal branch

- Zygomatic branch

- Buccal branch

- Marginal mandibular branch

- Cervical branch

Facial Nerve Function

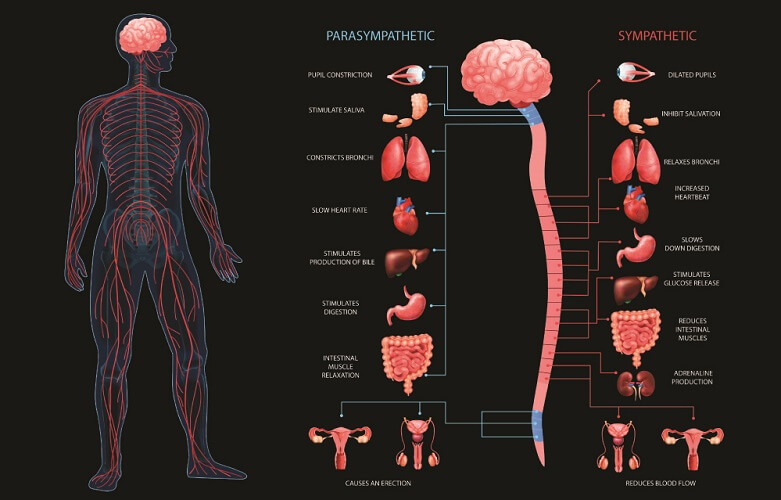

Facial nerve function requires an understanding of which nerves provide which effects. It is important to differentiate between the parasympathetic, sensory, and motor functions of the facial nerve.

The parasympathetic nervous system is part of the autonomic nervous system. Facial nerve parasympathetic fibers innervate the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands and encourage them to secrete saliva. The third and final parasympathetic function is control of the lacrimal glands for tear production.

The sensory functions of CN VII innervate the tongue to provide a sense of taste. Skin sensations of the face are not the responsibility of the facial nerve but of the trigeminal nerve.

Facial nerve motor functions are by far the most widespread. These nerve branches are essential for facial expression, communication, and the swallowing reflex.

Facial Nerve Branches

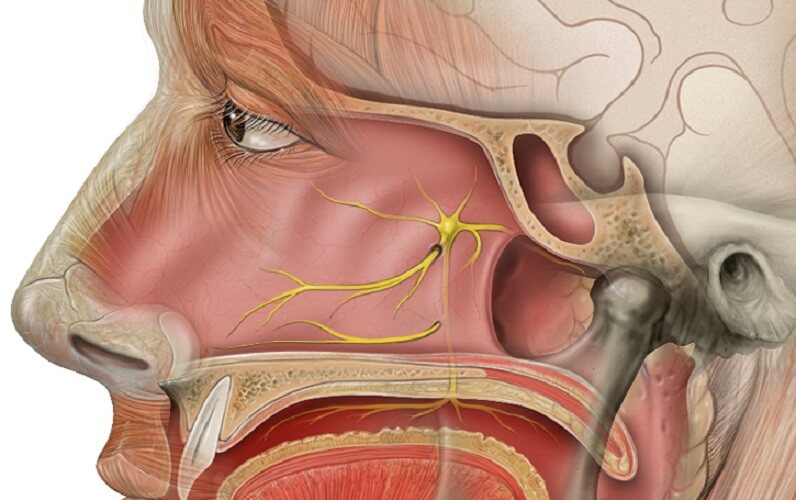

- Greater Petrosal Nerve

Also called the greater superficial petrosal nerve. Parasympathetic nerve fibers from the intermediate (sensory) root. In combination with other (non-facial) nerves, the greater petrosal nerve regulates blood flow to the nasal mucosa and allows taste perception in the front two-thirds of the tongue. Another shared task is the innervation of the lacrimal glands that produce tears.

- Nerve to Stapedius

The stapedius muscle is part of the inner ear and the smallest muscle of the body. It keeps the stapes bone in place. If this branch is damaged, the stapes may move excessively; even gentle sounds can sound very loud (hyperacusis).

- Chorda Tympani

The chorda tympani branch is a sensory nerve; innervation begins at the tongue mucous membrane and ends at the brainstem. The fibers that innervate the taste buds of the front two-thirds of the tongue are primarily special sensory afferent in type; some parasympathetic fibers travel on toward the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands.

- Posterior Auricular Nerve

Together with non-facial nerve branches, the posterior auricular nerve innervates the occipitalis muscle, occipitofrontalis muscle, and muscles around (and of) the ear. Many of these small muscles help to produce the auricular folds that attenuate our sense of hearing.

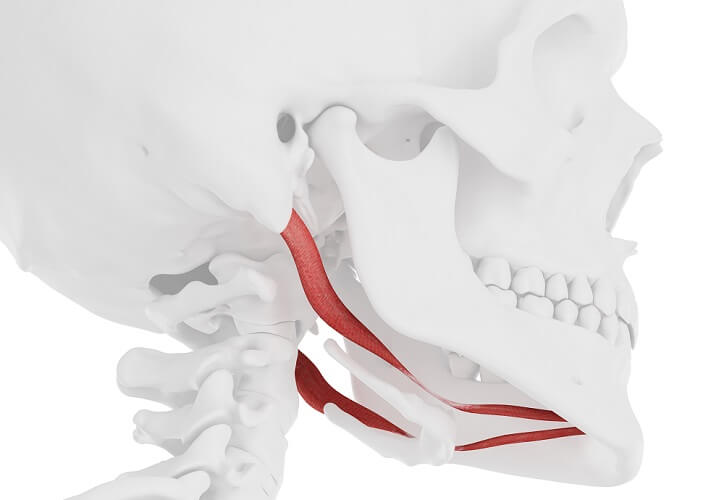

- Nerve to the Digastric Muscle

The facial nerve innervates the posterior belly of the paired digastric muscle. The digastric muscle is a loop of muscle under the jaw with two bands of muscle (bellies) connected by a tendon. Both bellies are essential for complex jaw movement and also lift the tongue bone when we swallow.

- Nerve to the Stylohyoid Muscle

The stylohyoid muscle connects the tongue bone (hyoid bone) to the base of the skull and is close to the above-mentioned posterior belly of the digastric muscle. It is one of a group of muscles that helps us to swallow.

- Temporal Branch

This branch innervates three muscles – the frontalis muscle of the forehead, the orbicularis oculi that closes the eyelid, and the corrugator supercilii muscle that, when contracted, brings the eyebrows toward the nose.

- Zygomatic Branch

This is another nerve that helps to control the orbicularis oculi of the left or right eyelid. Innervation of the eye muscles is extremely complex. When the facial nerve is damaged, a common symptom is drooping eyelids.

- Buccal Branch

The buccal branch of the facial nerve means we can move the orbicularis orbis that circles the mouth, the buccinator muscle that sits between the maxilla and mandible and keeps food close to the teeth when chewing, and the zygomaticus muscle. The zygomaticus muscle is essential if you feel like smiling.

- Marginal Mandibular Branch

The paired mentalis muscle in the centre of the chin lifts the surrounding skin and gives us the opportunity to pout.

- Cervical Branch

The cervical branch is the final branch of the motor root of the facial nerve. Cervical relates to the neck, and the broad, paired sheet of the platysma muscle runs from the corners of the mouth to just over the collar bones. It is essential for lower facial expression and brings the corners of the mouth downwards.

Facial Nerve Damage

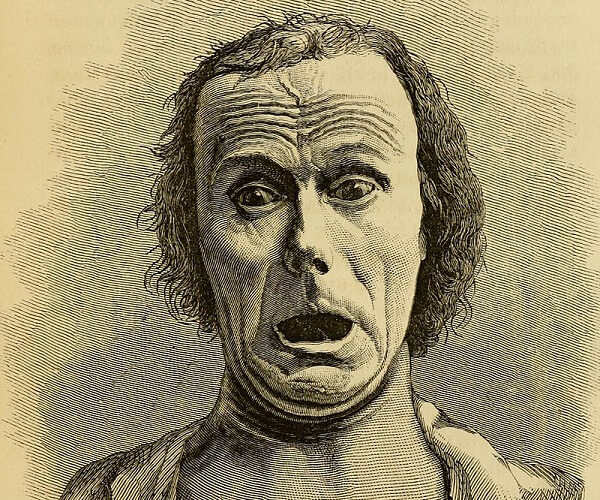

Facial nerve damage can cause paralysis, hyposensitivity, or hypersensitivity of any associated innervated structure.

Where the damage occurs is important – intracranial lesions may cause symptoms along the length of the nerve. A term often associated with facial nerve disorders is palsy. Palsy encompasses muscle weakness, loss of sensation, uncontrolled movement, and paralysis.

Facial nerve disorders can be the result of Bell’s palsy, skull base or ear tumors, infection, inflammation, stroke, and congenital anomalies. As facial nerve disorders are relatively common, most hospitals with a neurological department will provide extensive patient information about facial nerve disorder diagnosis and treatment. Treatment may require physiotherapy to regain muscle range of motion and strength.

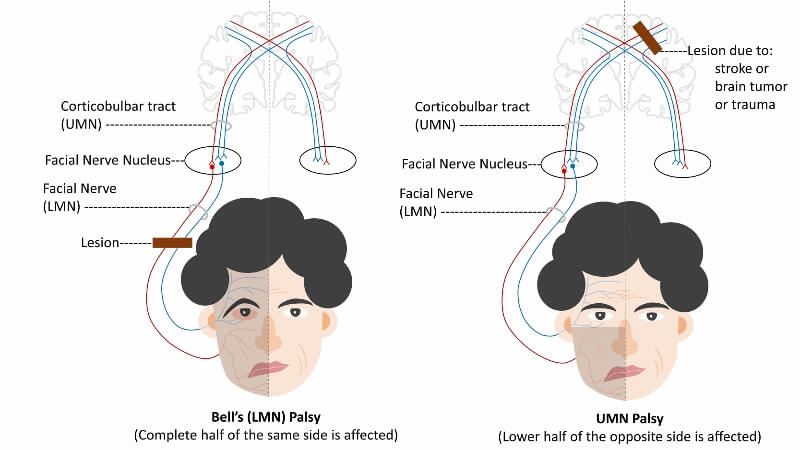

Bell’s palsy begins rapidly, starting with pain behind the ear. This evolves into paralysis on one side of the face and often a loss of taste sensation. People with diabetes are more likely to suffer from this disorder. While we do not yet know exactly what causes Bell’s palsy, Lyme disease and viral herpes are responsible for some cases. Bell’s palsy specifically refers to CN VII damage. A stroke and other causes rarely attack a single structure.

The most common cause of facial nerve damage is an ischemic stroke. This usually affects one side of the lower face. Remember that both brain hemispheres control the upper face; only the contralateral hemisphere controls the lower part.

If a blood clot in the brain stops oxygen from reaching the motor cortex of the left hemisphere, the result could be right-sided paralysis of the muscles of the right cheek, mouth, and neck. This is due to damage of the lower motor neurons. The other hemisphere will attempt to take over the role of the damaged side as regards the upper face muscles.

If the brainstem is damaged, the muscles of the upper and lower face will be affected. This is because the upper motor neurons are affected.