Definition

The Yersinia pestis bacterium is associated with the disease known as plague. The genus Yersinia is a member of the enterobacteria family and includes three human pathogens. One of these – Yersinia pestis – is a gram-negative, non-motile, non-spore-forming coccobacillus. It can grow in a wide range of temperatures and depends on other animals in order to pass on to humans – it is a zoonotic bacteria and an obligate parasite.

What is Yersinia Pestis?

Yersinia pestis is a facultative anaerobic coccobacillus. This means it can grow in the presence or absence of oxygen and has a shape that bridges the round forms of cocci and the rod-like features of bacilli. They look like short ovals under a microscope.

A Yersinia pestis bacterium is non-motile and cannot move through its environment. To multiply, it requires a host animal. Yersinia pestis is, therefore, an obligate parasite. These bacteria were first discovered as the cause of plague in 1894 by Alexandre Yersin of the Pasteur Institute in Paris.

Yersinia Pestis Transmission

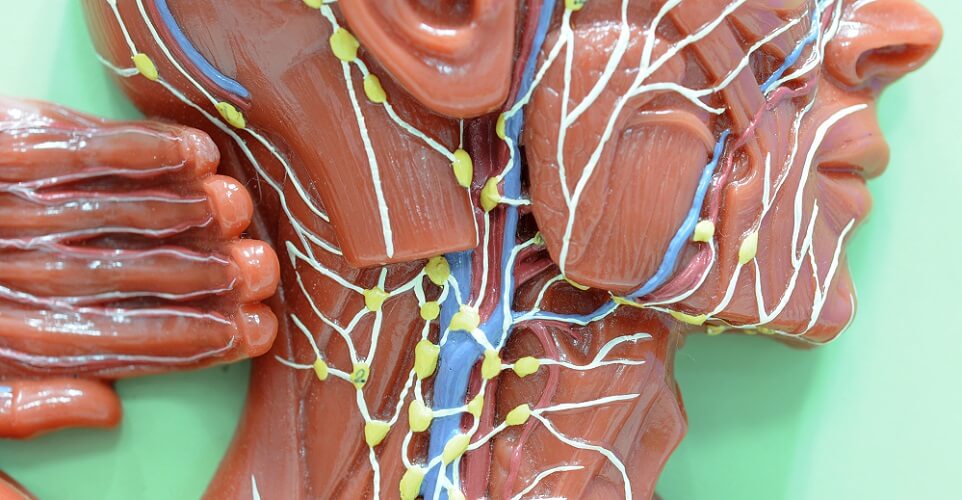

Y pestis is the only member of the enterobacteria family which transmits through flea vectors. It grows throughout the reticuloendothelial system (RES). The RES covers a wide range of tissues – blood, lymph nodes, general connective tissue, liver, lungs, spleen, and bone marrow.

Yersinia pestis bacteria can infect all mammals, the most common being rodents. When humans come into contact with infected rodents, fleas carried by the rodents can jump to the new host. The digestive tract of these fleas may contain infected rodent blood. When a flea feeds on human blood, many different types of bacteria can be transmitted into the bloodstream, including Y. pestis.

Yersinia pestis causes an infection called plague. Plague is relatively common in rodents, even today. In North America it primarily affects prairie dog colonies, killing anywhere up to 100% of infected populations. However, most rodents become partially resistant and populations are usually controlled rather than wiped out. As humans continue to encroach upon animal habits, they come into contact with infectious diseases normally limited to enclosed habitats. This scenario also seems to be the cause of the COVID-19 pandemic.

When an animal is not particularly affected by a Yersinia pestis infection, it is called an enzootic host. Y. pestis depends on the enzootic cycle where it is transmitted between partially-resistant mammals and flea vectors. When fleas come into contact with more susceptible mammals – epizootic hosts – large populations of epizootic organisms can die.

Most of us have heard of the Yersinia pestis bubonic plague epidemics of medieval times. Between 1347 and 1351, 30 to 50% of the European population died of the plague, most commonly the elderly and frail. The cause was the enzootic urban brown rat that carried flea vectors. These fleas jumped onto epizootic humans living in close proximity to the rats and passed on Y. pestis from their gastrointestinal tract to human blood upon biting and feeding. Fleas defecate as they feed, so it is also possible to become infected in this way.

While the most common form of Yersinia pestis transmission is the flea, it is possible to become infected if you eat an infected mammal or come into contact with the body fluids of dead plague victims or partially resistant infected animals. It is also possible to be infected through the respiratory droplets of infected hosts.

When untreated, mortality rates in enzootic mammals are very high (66% to 93%). If treated with antibiotics, this rate can drop to approximately 16%; the earlier an infection is treated, the greater the chance of survival.

Most modern plague cases occur in Africa, particularly Madagascar and the central African states.

Yersinia Pestis Symptoms

Yersinia pestis symptoms depend on the type of infection – bubonic, septicemic, or pneumonic. For all types, incubation times between exposure to Yersinia pestis and symptoms are between one to six days.

Yersinia Pestis: Bubonic Plague

The most common form of plague is bubonic plague. Once an infected flea vector has bitten a human or mammal, Y. pestis bacteria enter the bloodstream and make their way to the lymph nodes. Here, conditions are perfect for replication.

An infection causes swelling and pain in the lymph node(s) positioned closest to the bite. A swollen and painful lymph node is called a bubo – hence the name bubonic plague. Eventually, the lymph nodes fill with pus as the immune system sends in white blood cells and produces antibodies to kill the foreign bacteria. The rate of Y. pestis growth often makes this a losing battle – antibiotic therapy is required. If the infection takes over, it can move to the lungs and also cause pneumonic plague.

Bubonic plague symptoms begin with sudden-onset fever, headache, and chills. One or more lymph nodes become swollen and painful (buboes).

Yersinia Pestis: Septicemic Plague

When Y. pestis enters the bloodstream and multiplies, the result is septicemic plague. This infection spreads throughout the body at a rapid rate. Buboes are not always present, but infection of this type can also cause both bubonic and pneumonic plague types. This is because blood flow brings the bacteria to the lymph nodes and lungs. Signs of necrosis are often present in the skin, toes, nose, and fingers.

In 2008, an elderly woman living in a rural region of California died of septicemic plague after being infected at home. Living in a neglected home with evidence of rodent droppings, she was already extremely ill upon hospital admission. As this bacterial infection type is quite rare, Yersinia pestis Gram-stain results arrived too late for antibiotic therapy to be of use.

Yersinia Pestis: Pneumonic Plague

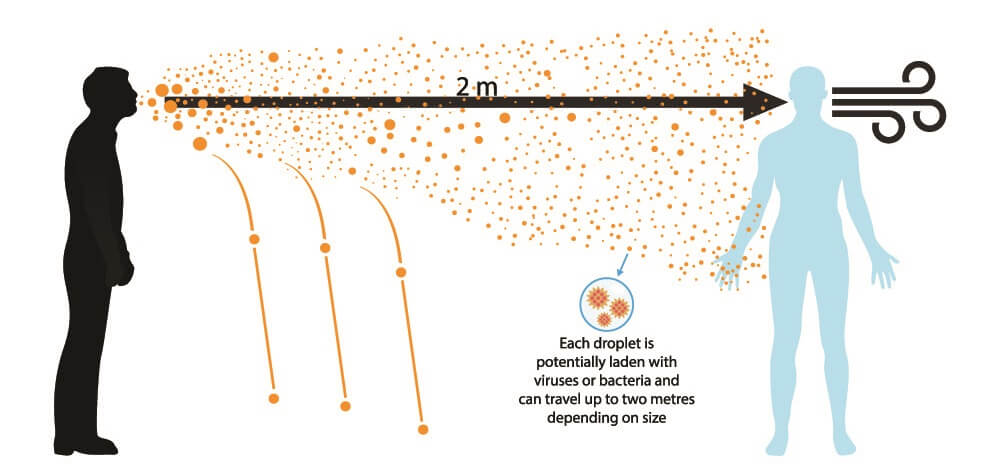

The most virulent form of plague is pneumonic plague. Here, infected droplets that travel via the coughs and sneezes of infected hosts enter the lungs of healthy victims. In the lungs, bacteria growth conditions are perfect; the incubation time is much less than that of bubonic plague and symptoms can begin as early as 24 hours after contact. Pneumonic plague is the only type of plague that can be transmitted from person to person.

Symptoms are almost similar to that of bubonic plague with fever, headache, and chills. This is accompanied by respiratory symptoms such as chest pain, cough, and shortness of breath.

Yersinia Pestis Treatment

Today, Yersinia pestis treatment is straightforward – antibiotics. People suffering from the pneumonic form need to be kept in isolation to prevent spread. They must remain so until at least four days after the initiation of antibiotic treatment.

The most effective antibiotic for pneumonic Y. pestis infection is streptomycin. This is administered as an intramuscular injection or intravenously until three days after the body temperature has returned to normal.

Bubonic and septicemic forms of plague respond to intravenous chloramphenicol administered for ten days. For less severe cases, tetracycline antibiotics are the drug of choice and can be given as an oral medication.

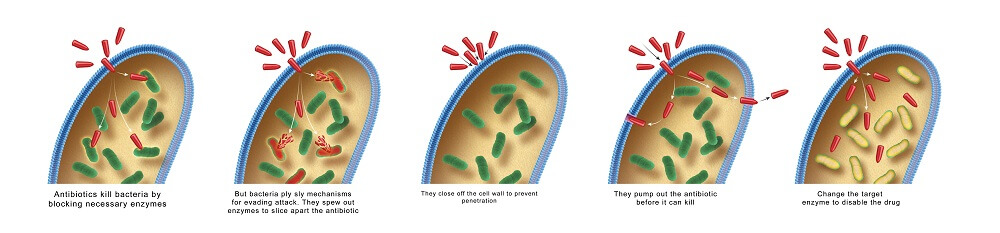

It is now becoming apparent that some Yersinia pestis strains have become resistant to antimicrobial agents (antibiotics). This has especially been seen in the recent Madagascar infections. Resistant Y. pestis genes carried in the bacterial plasmid (non-chromosomal DNA) mean that alternative treatments will be necessary in the future.

As plasmids can transfer between different bacteria or develop their own genes that differ from the genetic sequences of the bacterial chromosome, Y. pestis may eventually become multidrug-resistant. Due to its fatal course without modern treatment and the fact that the World Health Organization sees plague as a re-emerging disease, researchers are looking at antibiotic alternatives.

Furthermore, plague is listed as a Category A agent by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a potential source of biological weapons. Aerosol forms of pneumonic plague could cause international pandemics with high mortality rates should antibiotic production fail to cover the global population.

The use of plague as a bioweapon is nothing new. As far back as 1347, the Tartars would catapult dead plague victims into fortified cities. Bubonic plague was transmitted via ceramic shells containing infected fleas during the Japanese attack on China in World War II.

Yersinia pestis vaccines are currently being studied that do not require the use of a live vaccine. The use of flagellin – a structural protein that also acts as an immune response-promoting agent – in combination with Yersinia pestis antigens – is showing promising results.