Stomach Definition

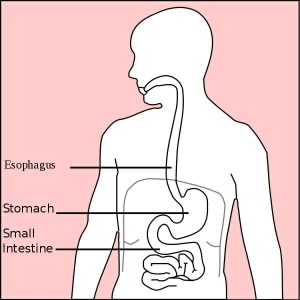

The stomach is a muscular organ that is found in our upper abdomen. If we were to locate it on our bodies, it can be found on our left side just below the ribs. In simple terms, the stomach is a kind of digestive sac. It is a continuation of the esophagus and receives our churned food from it. Therefore, the stomach serves as a kind of connection between the esophagus and the small intestine, and is a definite pit stop along our alimentary canal. Muscular sphincters, which are similar to valves, allow some separation between these organs.

The stomach’s functions benefit from several morphological attributes. The stomach is able to secrete enzymes and acid from its cells, which enables it to perform its digestive functions. With its muscular lining, the stomach is able to engage in peristalsis (in other words, to form the ripples that propel the digested food forward) and in the general “churning” of food. Likewise, the abundant muscular tissue of the stomach has ridges in its linings called rugae. These increase the surface area of the stomach and facilitate its functions, which we will describe in more detail below.

The image illustrates the esophagus, stomach, and intestinal regions of the human body

Functions of the Stomach

As mentioned before, the stomach is first and foremost a principal site of digestion. In fact, it is the first site of actual protein digestion. While sugars can begin to be lightly digested by salivary enzymes in the mouth, protein degradation will not occur until the food bolus reaches the stomach. This breakdown is carried out by the stomach’s pepsin enzyme. The stomach’s roles can essentially be distilled down to three functions.

Much like an elastic bag, the stomach will provide a place for varied amounts of swallowed food to rest and digest in. Hence, the stomach is a storage site. The stomach will also introduce our swallowed food to essential acids. The cells in the stomach’s lining will excrete a strong acidic mixture of hydrochloric acid, sodium chloride, and potassium chloride. This gastric acid, or colloquially known as gastric “juice,” will work to break down the bonds within the food particles at the molecular level. Pepsin enzyme will have the unique role of breaking the strong peptide bonds that hold the proteins in our food together, further preparing the food for the nutrient absorption that takes place in the small (mainly) and large intestines. This brings us to the third task the stomach has, which is to send off the churned watery mixture to the small intestine for further digestion and absorption. It takes about three hours for this to occur once the food is a liquid mix.

The stomach’s main roles:

- Food storage

- Acidic breakdown of swallowed food

- Sends mixture on to the next phase in the small intestine

Structure of the Stomach

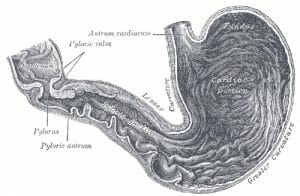

The archaic illustration depicts the different regions of the stomach

Although we have briefly discussed the location and physical traits of the stomach, it is important to detail the structure of the stomach, as well. The stomach begins at the lower esophageal sphincter that discerns the cut-off point of the esophagus. The stomach itself is very muscular. When the muscularis externa layers are dissected, one can visualize three distinct layers coined the longitudinal, circular, and oblique layers. The first region of the stomach is called the cardia. It is the layer closest to the esophagus and it contains cardiac glands that secrete mucus. Mucus protects the delicate epithelial lining of many tissues in the human body. This region is followed by the fundus, which is the superior arch of the stomach. Importantly, the fundus has the special function of containing gastric glands that release a cocktail of gastric juices. This region is followed by the body of the stomach, which is coated with rugae and is the largest region. Rugae, in turn, help facilitate digestion by increasing the site’s surface area. Finally, this section is followed by the pylorus region, which is closest to the exit into the duodenum of the small intestine and is pinched off by the pyloric sphincter.

Four regions of the stomach:

- Cardiac

- Fundus

- Body

- Pylorus

Common Stomach Issues

Almost every person has experienced a stomach related issue at one point in their lives. Perhaps the most common ones are indigestion and heartburn. These issues can be resolved quite easily with over-the-counter tablets (i.e. tums), but there is no denying that they are unpleasant experiences. However, there are more chronic illnesses that afflict many people. One of these is the gastroesophageal reflux disease, commonly known as GERD or Acid Reflux. GERD afflicts up to 3 million Americans each year, and is a physiological result of when the lower esophageal sphincter will not close properly. The principal function of this sphincter is to prevent food and stomach acids from regurgitating up the esophageal canal. While a healthy stomach has tons of mucus and barriers strong enough to prevent stomach acids from wreaking havoc on the epithelium, the esophagus is not quite so lucky. This, of course, has the long-term implications of damaging those delicate epithelial cells. When a patient does not have the sufficient barriers to prevent damage within the stomach, a medical issue that arises are peptic ulcers. Ulceration refers to the sores that pierce through an organ. When the stomach is not sufficiently protected from contact with these highly acidic acids, we do run into the issue of perforating the tissue and potentially having the stomach juices leak – which by all means requires urgent medical attention. These sores are very painful and recurrent in patients with peptic ulcer disease.

There are other red flag symptoms that present in the urgent or emergency care setting that indicate a stomach issue. These include a burning sensation in the chest (heartburn), piercing or diffuse abdominal pain, blood in the stool, and vomiting or diarrhea.

Quiz

1. How many hours does it take for the stomach to release the food to the small intestine?

A. 1

B. 2

C. 3

D. 4

2. Which of the following is the largest region of the stomach?

A. Cardia

B. Fundus

C. Body

D. Pylorus

3. Which region of the stomach releases gastric juice?

A. Cardia

B. Fundus

C. Body

D. Pylorus

References

- Hoffman, Matthew MD (2017). “Picture of the Stomach: Human Anatomy.” Web MD. Retrieved on 2017-08-26 from http://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/picture-of-the-stomach#1

- MedicineNet (2017). “Medical Definiton of Stomach.” MedicineNet. Retrieved on 2017-08-27 from http://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=5560

- Medline Plus (2017). “Stomach Disorders.” Medline Plus. Retrieved on 2017-08-28 from https://medlineplus.gov/stomachdisorders.html