Definition

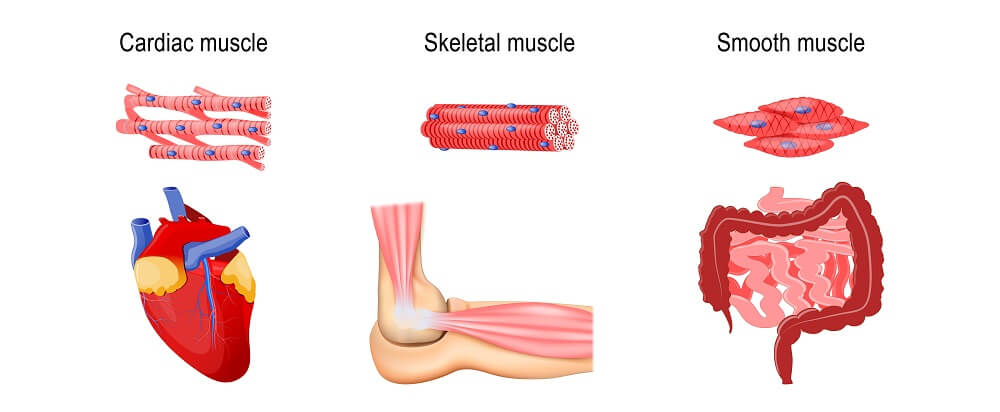

The word muscle atrophy comes from the Greek a (without) and trophe (nourishment). It refers to the breaking down of muscle fibers and is usually described as occurring in skeletal muscle; however, cardiac and smooth muscle also atrophy. Muscle atrophy mechanisms are divided into three groups – physiologic, pathologic, and neurogenic. While some forms can be reversed, others cannot.

What is Muscle Atrophy?

Muscular atrophy affects skeletal, smooth, and heart muscle; the term describes a loss of tissue mass. Atrophy occurs in all tissues and specifically refers to a reduction of tissue caused by smaller or fewer cells.

There are three ways in which muscle can atrophy (the verb form of atrophy is no different from the noun):

- Physiologic atrophy

- Pathologic atrophy

- Neurogenic atrophy

Different muscle atrophy causes apply according to these three types. Some can be reversed, some can perhaps be stabilized. The main causes will be discussed in more detail under the muscle atrophy mechanisms heading.

The opposite form of atrophy is hypertrophy where excess muscle tissue is produced.

All muscle types can lose mass. Loss of skeletal muscle density is a natural biological process because it is a storage area for amino acids. This means that during starvation scenarios we can still access protein sources from our muscles.

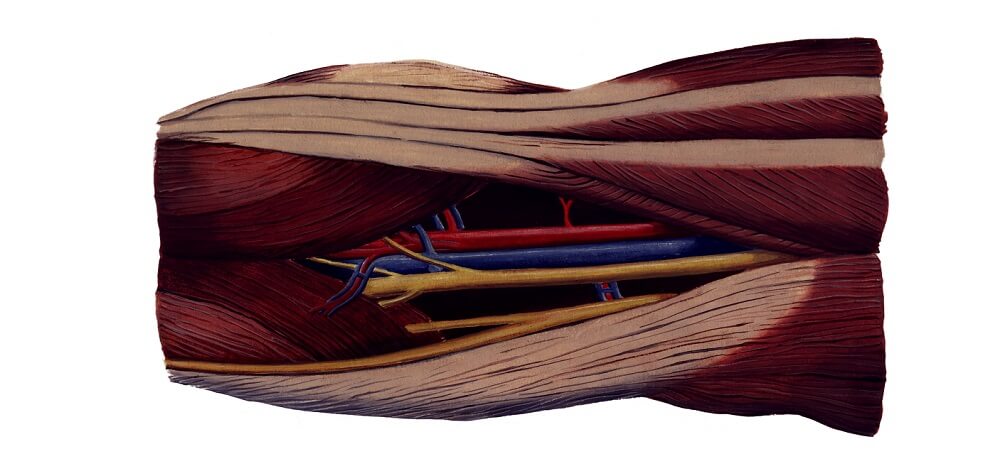

Skeletal Muscle

Atrophy of skeletal muscle leads to weakness in the muscles that allow non-automated movement. A whole range of diseases and disorders cause this form, as well as a sedentary lifestyle. Even short-term inactivity can cause atrophy such as when wearing a cast.

Smooth Muscle

Atrophy of smooth muscle commonly affects the digestive tract but also the urinary tract and the respiratory, vascular, and reproductive systems. Disorders linked to smooth muscle atrophy range from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) to fertility problems.

Cardiac Muscle

Atrophy of cardiac muscle is associated with aging; however, cancer, recreational drug use, and early heart disease can also be responsible.

Heart and skeletal muscle atrophy go hand-in-hand. This might be because heart muscle cells (cardiomyocytes) secrete a chemical called myostatin. Myostatin seems to control the rate of skeletal muscle wasting. When heart muscle atrophies it produces more myostatin and this speeds up the atrophy mechanism.

Muscle Atrophy Causes

The three muscular atrophy causes listed earlier use different ways to negatively affect muscle mass. They affect the regeneration rates and lifespans of muscle cells.

The average skeletal muscle cell lives for around fifteen years. These cells do not multiply by mitosis. Instead, specialized cells called mononucleated quiescent cells repair damaged cells.

When we gain muscle mass through exercise we do not increase the number of muscle cells in our body. Instead, existing cells increase in size much like fat cells. The muscles of bodybuilders are examples of skeletal myocyte hypertrophy.

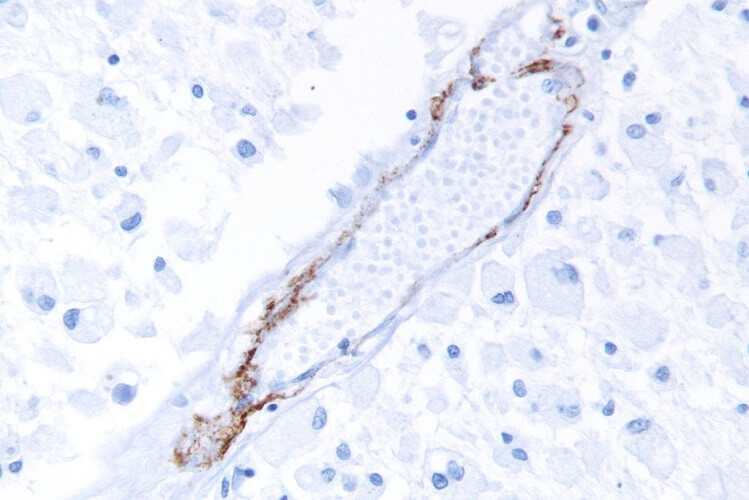

Smooth muscle is the quickest to regenerate; smooth muscle cells are the only type of muscle cell that can divide and multiply. Special cells called pericytes also have the ability to produce new smooth muscle cells.

Cardiac muscle cells are the slowest to regenerate. It used to be thought this was not possible; however, tests on people born during nuclear bomb testing in the 1950s and early 1960s have shown that cardiomyocytes can regenerate.

The higher levels of radiation during these two decades meant that all developing embryos absorbed more carbon-14 into their DNA than during other decades. Later tests have now shown that although half of their cardiomyocytes still contain more carbon-14 than usual, half does not. The original heart muscle cells had been replaced.

Up to the mid-twenties about 1% of cardiomyoctyes are replaced every year. This percentage gradually decreases by half by the time we reach our fiftieth year.

Physiologic Atrophy

Physiologic atrophy is normal atrophy. For example, after a woman gives birth the muscle of her uterus will decrease in mass. Physiologic atrophy also occurs during fetal development.

Pathologic Atrophy

There are many causes of pathologic atrophy.

Low muscle mass means that the muscle cells have become smaller. This is done to conserve energy. Muscle atrophy after surgery is the result of low activity levels due to pain. After-cast muscle atrophy is very visible once a cast is taken off.

As muscle cells use a lot of energy, making them smaller reduces energy use. Someone who regularly jogs may have very visible muscle atrophy in the legs and arms after recovery from surgery. This type of atrophy is reversible when the person makes use of the affected muscle or muscle group again.

A low blood supply causes atrophy in all types of tissue, not just muscle. When a muscle cell is completely starved of oxygen it dies. While smooth muscle cells can regenerate if the oxygen supply is restored, this is not the case for other myocytes.

Low blood supply can cause muscular atrophy all over the body or be localized. When a person is bed- or wheelchair-bound, pressure on a single muscle group can reduce the blood supply at a localized point. Without a good blood supply, muscle cells are unable to get sufficient access to oxygen or nutrients.

Atrophy means without nourishment so starvation and malnutrition also cause atrophy of the muscles. Very low levels of protein in the diet mean that muscle cells cannot expand. Without a regular source of protein a child is very likely to suffer from kwashiorkor – long-term protein deficiency. Muscle is then absorbed to provide protein for the rest of the body.

Our hormone levels are also responsible for muscular atrophy. One example is women going through the menopause. During menopause females produce less estrogen. When estrogen levels are low, fat tissue increases and bone and muscle mass decrease.

Neurogenic Atrophy

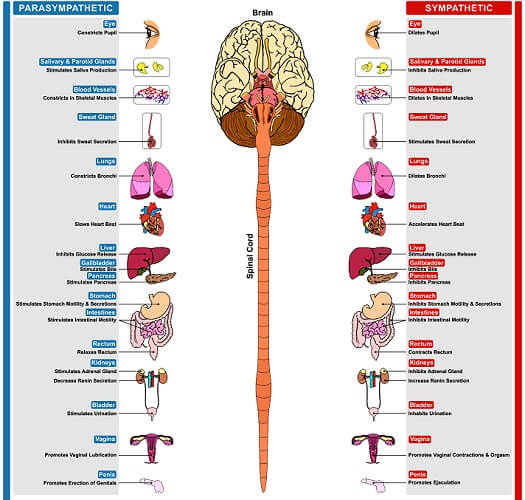

If nerves are damaged the muscles to which they connect do not respond efficiently or at all. The effect is the same as plaster cast muscle atrophy – localized skeletal atrophy of the muscles connected to that nerve. But unless the nerve is repaired this type of atrophy is irreversible. After a damaged nerve heals, physiotherapy can help to increase muscle mass and function.

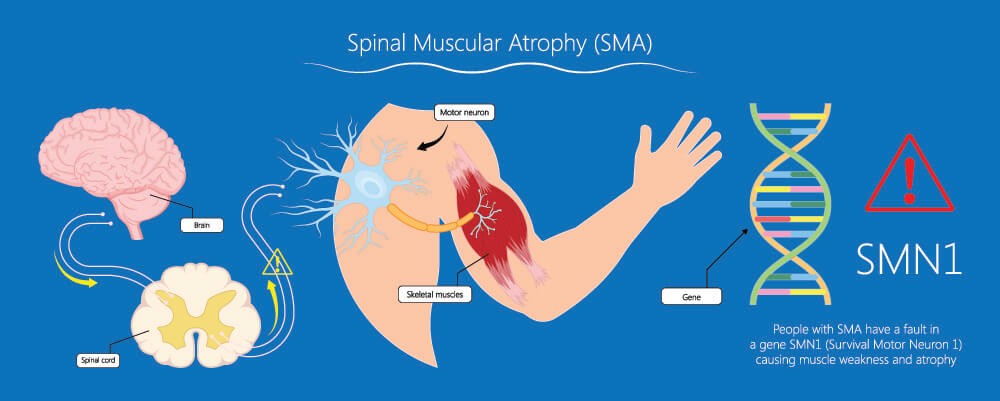

When motor nerves in the central nervous system are damaged or if the genes that control them are faulty such as with spinal muscular atrophy, muscle wastage occurs all over the body. Autonomic nerve damage reduces mass and function in the smooth muscle of the digestive tract, urinary tract, reproductive system, respiratory system, and blood vessels.

Neurological disorders have a huge effect on muscle mass. The causes range from trauma, surgical complications, and even deep burns. Infections like polio can damage the nerves. Other common causes of neurogenic atrophy are genetic disorders.

Neurological disorders have a huge effect on muscle mass. The causes range from trauma, surgical complications, and even deep burns. Infections like polio can damage the nerves. Other common causes of neurogenic atrophy are genetic disorders.

The neurogenic type is sometimes included within the pathogenic category; however, its broad scope puts neurogenic muscle atrophy in a classification all of its own.

Muscle Atrophy Mechanisms

Muscular atrophy mechanisms are the same. It is the cause that differs.

Low levels of cell nutrition happen because the blood supply is affected or there is a lack of nutrition or oxygen in the blood.

In the case of damaged blood vessels, no nutrients or oxygen can reach the affected area even if they are in good supply. Serious illness makes the body send blood to the vital organs rather than the muscles as this is more effective for survival.

Vascular disease and inflammation make oxygen and nutrient transport to the muscles difficult.

All of these causes have a common result. The red thread that passes through every type and cause of muscle atrophy is reduced metabolic activity.

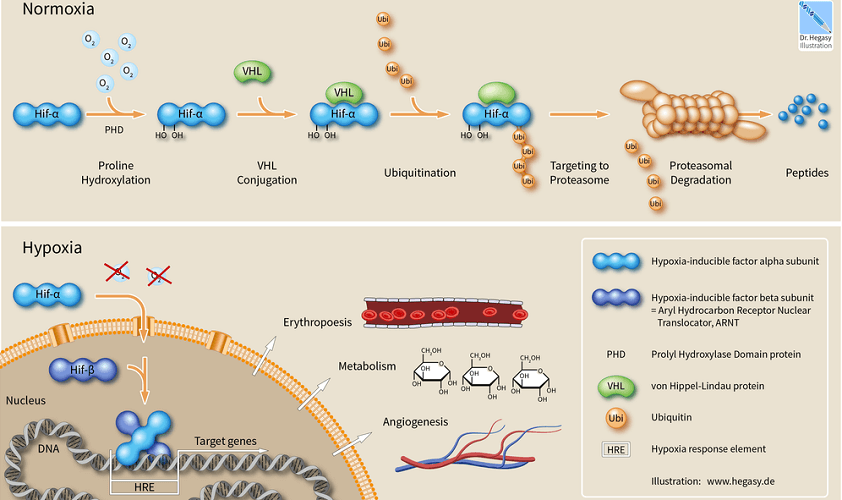

When a muscle cell does not receive enough nourishment or stimulation it stops producing proteins. Existing protein molecules degrade via a cell signaling pathway called the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway.

The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (UPP) is essential as it breaks down proteins for use all over the body. Proteins are the building blocks of life; the food we eat and the non-essential amino acids our bodies produce are usually sufficient for our metabolic needs. Without available protein, the body breaks down less-vital tissues and protein storage areas (the muscles). It can then use the released amino acids to feed more important structures. When we are starving, muscles are of less importance to our survival than the brain, heart, kidneys, liver, and lungs.

Ubiquitin is itself a protein. When it binds to another protein it becomes a signaling molecule. Proteasomes enable protein breakdown so that smaller peptide chains and amino acids can be used in the body. When ubiquitin binds to a protein this tells a proteasome that the attached protein needs to be broken down. The UPP occurs inside the cell.

A starved cell can also consume its organelles to get the nutrients it needs. This process is called autophagy and is a survival mechanism. If the blood supply to a muscle is restored or a disease process is managed an autophagic muscle cell might recover. If nothing is done the cell will continue to digest its organs until it dies.

Muscle Atrophy Symptoms

Muscle atrophy symptoms depend on the affected muscle. Cardiomyocyte atrophy causes a whole range of circulatory symptoms. Smooth muscle atrophy in the intestine may become so severe that a colostomy bag must be fitted. Skeletal muscle atrophy symptoms range from muscle (group) weakness to immobility.

Weight loss is a symptom found in non-localized skeletal muscle forms. Muscle is denser than fat tissue. Although five pounds of each weigh the same, the volume of five pounds of muscle will be much smaller. Of course, inactivity and a low protein but high-calorie diet will cause weight gain in combination with muscle atrophy.

Even so, the muscle atrophy definition gives us its primary symptom – loss of muscle mass. All other symptoms – weakness, immobility, gastrointestinal problems, and muscular atrophy pain – are secondary to this.

Can Muscle Atrophy be Reversed?

If the nutrient and oxygen supply can be restored to a starved muscle cell in good time it might recover. This is not guaranteed.

Where skeletal muscle disuse is the cause of non-neurogenic atrophy, muscle atrophy recovery is possible. As long as an innervated muscle cell is not severely damaged and the supply of nutrients and oxygen can be restored, atrophy can be a reversible disorder.

Unfortunately, many of the causes of muscle atrophy are chronic. A severed major nerve cannot be fixed. Vascular and neurological degeneration are natural signs of aging. Such cases lead to continuous atrophy of muscle tissue that cannot be reversed.