Definition

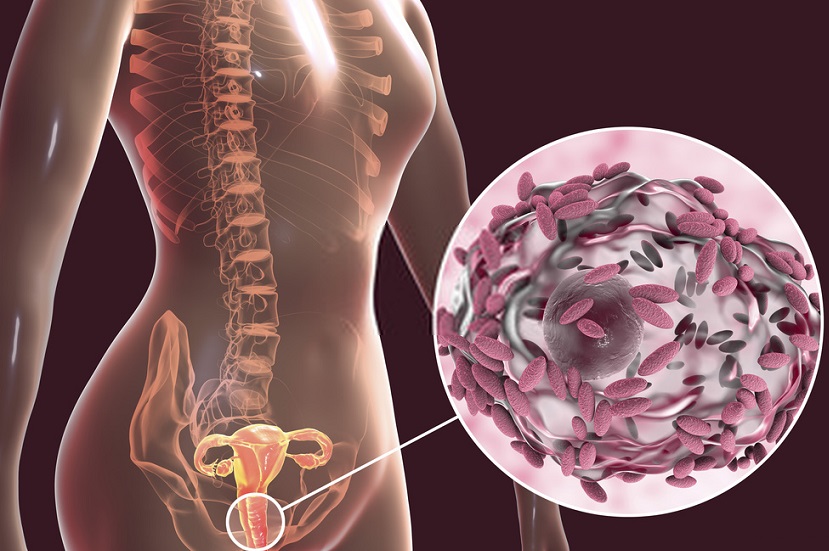

Gardnerella vaginalis is the name of a micro-aerophilic coccobacillus found in the vaginal flora. Gardnerella vaginalis does not cause bacterial vaginosis (vaginal infection) unless populations become dominant; recent findings seem to show that this bacterium may be part of the normal vaginal flora and not only the result of sexual transmission.

Gardnerella Vaginalis in Healthy Vaginal Flora

Gardnerella vaginalis can be a natural, non-pathogenic member of a healthy vaginal flora or can be contracted through sexual activity where a partner is a carrier of Gardnerella bacteria. Urethral colonization of Gardnerella occurs in males but this does not generally cause symptoms or need to be treated.

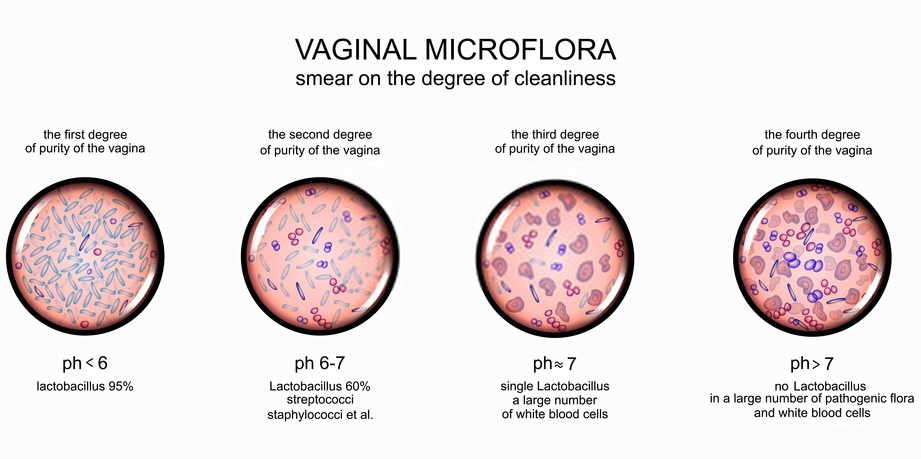

The vaginal flora or vaginal microbiota is primarily composed of the Lactobacillus species, in particular, Lactobacillus crispari, Lactobacillus gasseri and Lactobacillus jensenii. Other bacteria found in healthy females include Actinomycetes, Bifidobacterium and Gardnerella vaginalis. Pre-pubescent females may already have populations of Gardnerella in the vagina as from puberty onwards the vagina is no longer a sterile environment. Populations of this bacterium in healthy vaginal microbiota usually remain low during adult life stages unless the female in question has low immunity, is sexually active with multiple partners or if her partner has multiple partners, or if she regularly takes antibiotics; however, in and around the menopause populations of Gardnerella vaginalis often increase due to physiological and metabolic changes. While the presence of Gardnerella in children can often point to a history of sexual abuse, this is certainly not always the case and populations have been found in newborns of both genders.

High, healthy levels of protective Lactobacillus increase acidity levels in the vagina to between 3.8 and 4.5 through the secretion of hydrogen peroxide and lactic acid. An acidic environment of this level discourages the growth of potentially pathogenic bacteria. To control growth in Gardnerella vaginalis, Lactobacillus bacteria have a further function – they prevent many types of potentially harmful bacteria from attaching to the vaginal epithelium, whereby growth or colonization becomes difficult. In other words, a healthy microbiota consisting primarily of Lactobacillus protects the vagina from infection.

Yet certain circumstances can cause an imbalance in the vaginal flora. These circumstances range from hormonal changes and sexual activity to douching, diet, illness, and some medications. When Lactobacillus levels decrease, it then becomes possible for other bacteria to colonize the vagina and change its pH to suit them, eventually causing infection. The most common infection of the vagina is bacterial vaginosis; bacterial vaginosis is usually caused by Gardnerella.

How Does Gardnerella Cause Bacterial Vaginosis?

Gardnerella vaginalis is a non-motile, non-sporing, micro-aerophilic coccobacillus. This means that these bacteria are unable to move independently and require extremely low levels of oxygen. These levels are so low, G. vaginalis is often described as an anaerobic bacteria, yet in order to multiply they do need small amounts of O2. Simply put, oxygen levels in ambient air would be toxic to Gardnerella. As populations remain in one place where very little oxygen is found, imbalances in protective vaginal bacteria can allow for Gardnerella colonization. In most cases, overgrowth leads to the production of a biofilm.

What is a Biofilm?

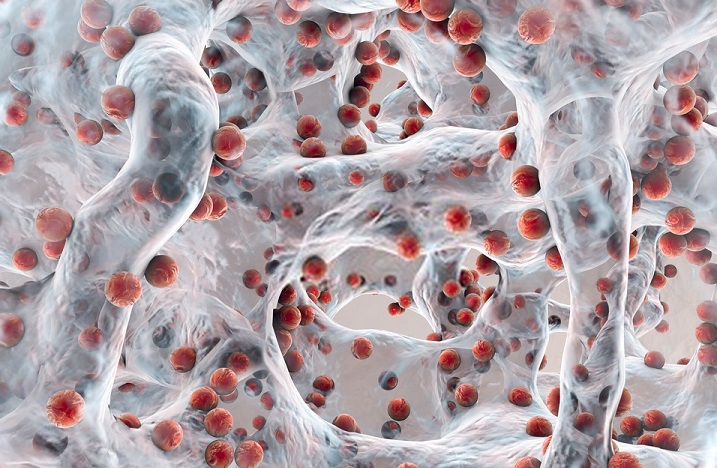

A single pathogenic bacteria cell cannot cause infection. This can only occur in environments where it can multiply with resulting populations colonizing a particular tissue or physiological system such as the vaginal epithelium and cardiovascular system, respectively.

Anywhere a microorganism accumulates, either inside the body or on kitchen worktops, in drainage and ventilation systems, and anywhere bacteria or fungi can survive, a biofilm can be formed. As a group, these microorganisms interact and communicate within the biofilm to help each other survive.

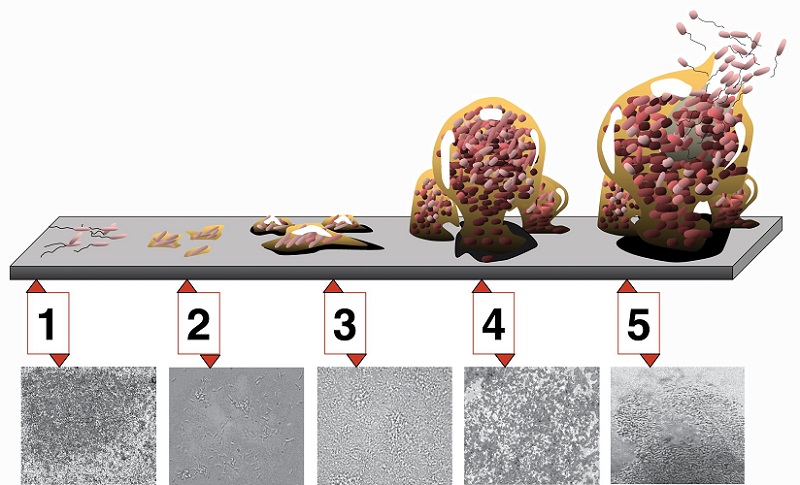

In an imbalanced vaginal microbiota, an initial layer of Gardnerella vaginalis will adhere to the vaginal wall. This first stage is known as initial reversible attachment. During this phase, any treatment to remove them will work quickly and effectively.

After initial attachment, these bacteria use surface proteins to further adhere to the epithelial cells of the vagina. This stage is known as irreversible attachment. In order to make use of the surface proteins, the environment in which Gardnerella lives must be beneficial to growth and survival. Once solidly attached to the vaginal tissue the next stage can commence. This is the creation of a microcolony, achieved through the multiplication of bacterial cells to produce a community. The moment a community is established, the bacteria produce extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) which create a slimy, protective layer. The EPS can form up to 90% of a biofilm layer and the sticky texture also traps nutrients as an additional food source for the bacteria within. Channels within the biofilm can provide a source of water and remove waste products. Furthermore, the biofilm matrix produces optimal temperatures for growth of the bacteria that have created it. The next stage, maturation, or in this case rapid multiplication of Gardnerella, is made possible through the characteristics of the biofilm.

Gardnerella Vaginalis and Bacterial Vaginosis

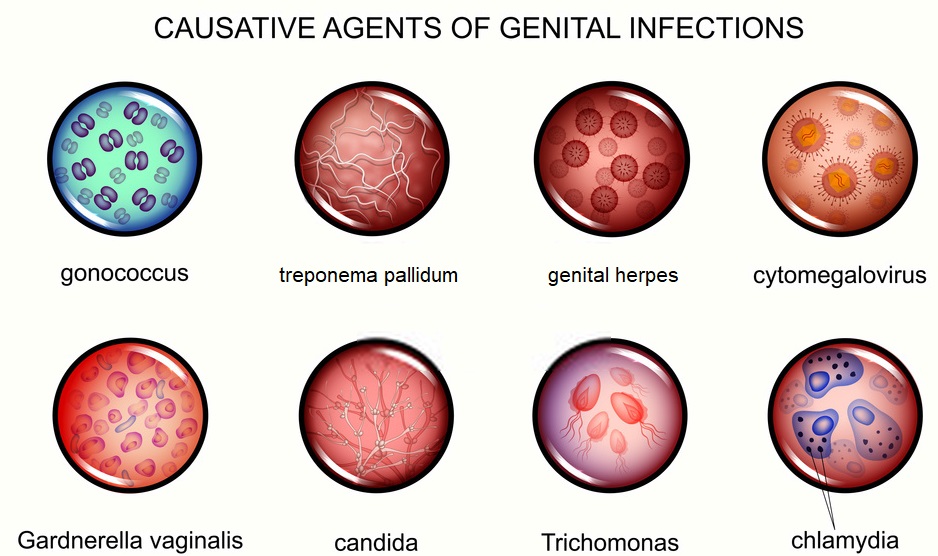

An interesting feature of G. vaginalis is its ability to engage in synergistic relationships with other pathogenic bacteria. It is often found that the initial colonization of Gardnerella will often lead to vaginal colonization of other harmful bacteria types. This is why Gardnerella vaginalis is considered the most virulent form of vaginal pathogen and is often listed as the single cause of bacterial vaginosis (BV).

While Gardnerella vaginalis is non-motile, the final stage of biofilm development – dispersal – is still possible through flows of discharge, mucus, and menstrual blood. If conditions become less advantageous, for example through a lack of nutrients or change in temperature, a proportion of cells will detach from the biofilm and travel to other areas to increase the chances of population survival. From all of the described information we can, therefore, surmise that a G. vaginalis infection is difficult to treat. Below the various biofilm stages: 1) initial attachment, 2) irreversible attachment, 3) maturation I, 4) maturation II, 5) dispersion

Gardnerella Vaginalis Symptoms

G. vaginalis symptoms in females in association with bacterial vaginosis are most commonly an odorous, ‘fishy’ smelling, thin vaginal discharge which can be white or yellow in color, fever, abdominal tenderness, and leukocytosis. Infection is not associated with significant pain or discomfort during sexual intercourse. When these bacteria enter the short female urethra a urinary tract infection (UTI) can result. However, an infection can also be asymptomatic, especially in males. Should G. vaginalis reach the urethra in either gender, the resulting UTI can lead to mild to severe pain and is difficult to treat once one or more biofilms have formed. Gardnerella colonization in pregnant women can cause premature labor and delivery, rupture and hemorrhage, and postpartum or postabortion septicemia.

Furthermore, Gardnerella infection can go on to cause other pathologies such as endometritis, chorioamnionitis, vaginal abscess, wound infections after genitourinary surgeries, pelvic inflammatory disease, and intrauterine infections which can themselves lead to spontaneous abortion or infertility.

In newborns, Gardnerella vaginalis colonization has been known to cause meningitis, urinary tract infection, conjunctivitis, pneumonia, and septicemia.

Gardnerella Vaginalis Treatment

G. vaginalis bacteria are associated with diamine production – chemicals which contribute to the characteristic fishy odor of this a vaginal infection. When the vaginal wall becomes colonized with Gardnerella vaginalis, the bacteria increase the pH to a level whereby their survival is optimized and protective Lactobacillus begins to die.

A normal vaginal pH is between 3.8 to 4.5; this is the result of hydrogen peroxide and lactic acid secretion by Lactobacillus and the results of epithelial glycogen metabolism. In the presence of estrogen, more glycogen is available and so more nutrients for the Lactobacillus. This explains why infection rates can rise in menopausal women whose estrogen levels are low. When G. vaginalis populations begin to grow, the acidifying effect of Lactobacillus is significantly reduced, creating an environment where multiple pathological bacteria can grow. This is why a Gardnerella infection also increases risk of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).

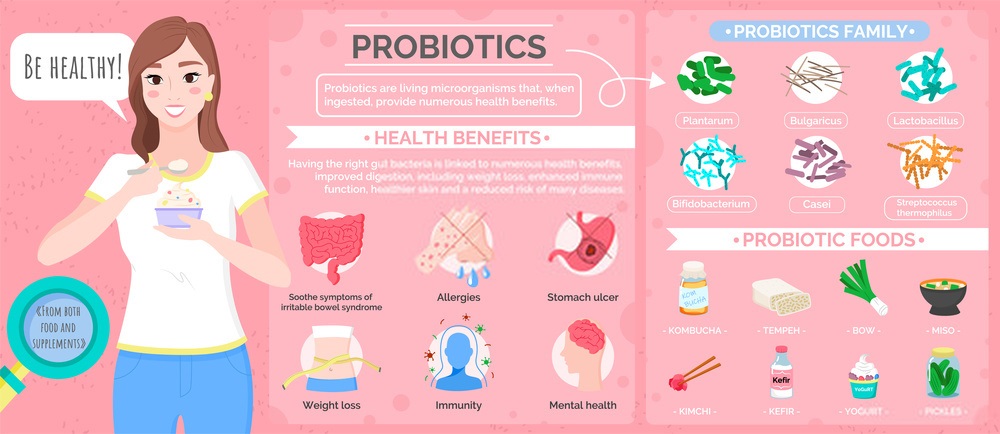

Gardnerella vaginalis treatments are currently limited to the use of antibiotics such as metronidazole and clindamycin. These can be administered as oral medications, creams or, in severe cases, intravenously. However, antibiotics also diminish populations of healthy bacteria and the increasing disadvantage of bacterial antibiotic resistance has led to a preference for new methods of BV treatment. Some studies have shown that up to 68% of bacteria in recurrent bacterial vaginosis are resistant to antibiotics. In addition, antibiotic treatments for other ailments in other physiological systems can also cause vaginal microbiota to become imbalanced. This means newer therapies are being studied for their efficacy. One of these is the use of a sucrose-based vaginal gel which feeds the healthy Lactobacillus and helps them to withstand or overthrow colonization by other pathogens. Another is the ingestion of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium in pill or drink form to replenish populations (see image below). Even vaginal douches using live yogurt containing healthy bacteria can return the vaginal microbiota to balance. Menopausal women may experience lower infection rates through hormone replacement therapy, where higher levels of estrogen increase glycogen levels in the vaginal epithelium and provide a food source for Lactobacillus.

Gardnerella vaginosis infection treatments, therefore, should encourage the growth of healthy bacteria and not wipe out entire populations of healthy and pathogenic microorganisms through antibiotics – at least not as first-line therapy. Healthy levels of estrogen, digestible sugars in the form of sucrose or honey, and reintroduction of Lactobacillus into the body either through the digestive tract or directly into the vagina seem to produce similar results as antibiotics but with less damage to healthy bacteria and fewer side effects.

Quiz