DNA Definition

Deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, is a biological macromolecule that carries hereditary information in many organisms. DNA is necessary for the production of proteins, the regulation, metabolism, and reproduction of the cell. Large compressed DNA molecules with associated proteins, called chromatin, are mostly present inside the nucleus. Some cytoplasmic organelles like the mitochondria also contain DNA molecules.

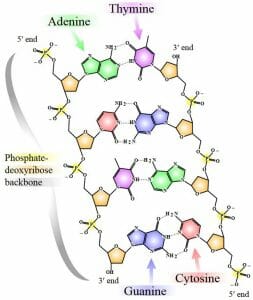

DNA is usually a double-stranded polymer of nucleotides, although single-stranded DNA is also known. Nucleotides in DNA are molecules made of deoxyribose sugar, a phosphate and a nitrogenous base. The nitrogenous bases in DNA are of four types – adenine, guanine, thymine and cytosine. The phosphate and the deoxyribose sugars form a backbone-like structure, with the nitrogenous bases extending out like rungs of a ladder. Each sugar molecule is linked through its third and fifth carbon atoms to one phosphate molecule each.

Functions of DNA

DNA was isolated and discovered chemically before its functions became clear. DNA and its related molecule, ribonucleic acid (RNA), were initially identified simply as acidic molecules that were present in the nucleus. When Mendel’s experiments on genetics were rediscovered, it became clear that heredity was probably transmitted through discrete particles, and that there was a biochemical basis for inheritance. A series of experiments demonstrated that among the four types of macromolecules within the cell (carbohydrates, lipids, proteins and nucleic acids), the only chemicals that were consistently transmitted from one generation to the next were nucleic acids.

As it became clear that DNA was the material that was transferred from one generation to the next, its functions began to be investigated.

Replication and Heredity

Every DNA molecule is distinguished by its sequence of nucleotides. That is, the order in which nitrogenous bases appear within the macromolecule identify a DNA molecule. For instance, when the human genome was sequenced, the nucleotides constituting each of the 23 pairs of chromosomes were laid out, like a string of words on a page. There are individual differences in these nucleotide sequences, but overall, for every organism, large stretches are conserved. The sugar phosphate backbone, on the other hand, is common to all DNA molecules, across species, whether in bacteria, plants, invertebrates or humans.

When a double-stranded DNA molecule needs to be replicated, the first thing that happens is that the two strands separate along a short stretch, creating a bubble-like structure. In this transient single-stranded region, a number of enzymes and other proteins, including DNA polymerase work to create the complementary strand, with the correct nucleotide being chosen through hydrogen bond formation. These enzymes continue along each strand creating a new polynucleotide molecule until the entire DNA is replicated.

Life begins from a single cell. For humans, this is the zygote formed by the fertilization of an egg by a sperm. After this, the entire dazzling array of cells and tissue types are produced by cell division. Even the maintenance of normal functions in an adult requires constant mitosis. Each time a cell divides, nuclear genetic material is duplicated. This implies that nearly 3 billion nucleotides are accurately read and copied. High-fidelity DNA polymerases and a host of error repair mechanisms ensure that there is only one incorrectly incorporated nucleotide for every 10 billion base pairs.

Transcription

The second important function of genetic material is to direct the physiological activities of the cell. Most catalytic and functional roles in the body are carried out by peptides, proteins and RNA. The structure and function of these molecules is determined by nucleotide sequences in DNA.

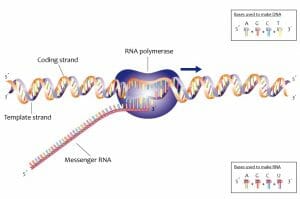

When a protein or RNA molecule needs to be produced, the first step is transcription. Like DNA replication, this begins with the transient formation of a single-stranded region. The single-stranded region then acts as the template for the polymerization of a complementary polynucleotide RNA molecule. Only one of the two strands of DNA is involved in transcription. This is called the template strand and the other strand is called the coding strand. Since transcription is also dependent on complementary base pairing, the RNA sequence is nearly the same as the coding strand.

In the image, the coding strands and the template strands are depicted in orange and purple respectively. RNA is transcribed in the 5’ to 3’ direction.

Mutation and Evolution

One of the main functions of any hereditary material is to be replicated and inherited. In order to create a new generation, genetic information needs to be accurately duplicated and then transmitted. The structure of DNA ensures that the information coded within every polynucleotide strand is replicated with astonishing accuracy.

Even though it is important for DNA to be duplicated with a very high degree of accuracy, the overall process of evolution requires the presence of genetic variability within every species. One of the ways in which this happens is through mutations in DNA molecules.

Changes to the nucleotide sequence in genetic material allows for the formation of new allele. Alleles are different, mostly functional, varieties of every gene. For instance, people who have B blood group have a certain gene resulting in a particular surface protein on red blood cells. This protein is distinct from the surface antigens in those who have blood group A. Similarly, people with sickle cell anemia have a different hemoglobin allele compared to those who do not suffer from the illness.

The presence of this variability allows at least some populations to survive when there is a sudden and drastic change to the environment. For instance, individuals carrying a mutated allele for hemoglobin are at risk for sickle cell anemia. However, they also have a higher chance of survival in regions where malaria is endemic.

These mutations and the presence of variability allow populations to evolve and adapt to changing circumstances.

Genetic Engineering

On another level, DNA’s role as genetic material and an understanding of its chemistry allows us to manipulate it and use it to enhance quality of life. For example, genetically modified crops that are pest or drought resistant have been generated from wild type varieties through genetic engineering. A lot of molecular biology is dependent on the isolation and manipulation of DNA, for the study of living processes.

Structure of DNA

When its definitive role in heredity was established, understanding DNA’s structure became important. Previous work on protein crystals guided the interpretation of crystallization and X-Ray differaction of DNA. The correct interpretation of diffraction data started a new era in understanding and manipulating genetic material. While initially, scientists like Linus Pauling suggested that DNA was perhaps made of three strands, Rosalind Franklin’s data supported the presence of a double helix.

The structure of DNA therefore, was elucidated in a step-wise manner through a series of experiments, starting from the chemical isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid by Frederich Miescher to the X-ray crystallography of this macromolecule by Rosalind Franklin.

Double Helix and Antiparallel Strands

The image is a simplified representation of a short DNA molecule, with deoxyribose sugar molecules in orange, linked to phosphate molecules through a special type of covalent linkage called the phosphodiester bond. Each nitrogenous base is represented by a different color – thymine in purple, adenine in green, cytosine in red and guanine in blue. The bases from each strand form hydrogen bonds with one another, stabilizing the double-stranded structure.

The structure of the sugar phosphate backbone in a DNA molecule results in a chemical polarity. Each deoxyribose sugar has five carbon atoms. Of these, the third and the fifth carbon atoms can form covalent bonds with phosphate moieties through phosphodiester bonds. A phosphodiester linkage essentially has a phosphate molecule forming two covalent bonds and a series of these bonds creates the two spines of a double-stranded DNA molecule.

Alternating sugar and phosphate residues results in one end of every DNA strand having a free phosphate group attached to the fifth carbon of a deoxyribose sugar. This is called the 5’ end. The other end has a reactive hydroxyl group attached to the third carbon atom of the sugar molecule and makes the 3’ end.

The two strands of every DNA molecule have opposing chemical polarities. That is, at the end of every double-stranded DNA molecule, one strand will have a reactive 3’ hydroxyl group and the other strand will have the reactive phosphate group attached to the fifth carbon of deoxyribose. This is why a DNA molecule is said to be made of antiparallel strands.

A DNA molecule can look like a ladder, with a sugar phosphate backbone and nucleotide rungs. However, a DNA molecule forms a three-dimensional helical structure, with the bases tucked inside the double helix. Hydrogen bonding between nucleotides allows the intermolecular distance between two strands to remain fairly constant, with ten base pairs in every turn of the double helix.

Complementarity and Replication

Nucleotide bases on one strand interact with those on the other strand through two or three hydrogen bonds. This pattern is predictable (though exceptions exist), with every thymine base pairing with an adenine base, and the guanine and cytosine nucleotides forming hydrogen bonds with each other. Due to this, when the sequence of a single strand is known, the nucleotides present in the complementary strand of DNA are automatically revealed. For instance, if one strand of a DNA molecule has the sequence 5’ CAGCAGCAG 3’, the bases on the other antiparallel strand that pair with this stretch will be 5’ CTGCTGCTG 3’. This property of DNA double strands is called complementarity.

Initially, there was debate about the manner in which DNA molecules are duplicated. There were three major hypotheses about the mechanism of DNA replication. The two complementary strands of DNA could unwind at short stretches and provide the template for the formation of a new DNA molecule, formed completely from free nucleotides. This method was named the conservative hypothesis.

Alternatively, each template strand could catalyze the formation of its complementary strand through nucleotide polymerization. In this semi-conservative mode of replication, all duplicated DNA molecules would carry one strand from the parent and one newly synthesized strand. In effect, all duplicated DNA molecules would be hybrids. The third hypothesis stated that every large DNA molecule was probably broken into small segments before it was replicated. This was called the dispersive hypothesis and would result in mosaic molecules.

A series of elegant experiments by Matthew Meselson, and Franklin Stahl, with help from Mason MacDonald and Amandeep Sehmbi, supported the idea that DNA replication was, in fact, semi-conservative. At the end of every duplication event, all DNA molecules carry one parental strand and one strand newly created from nucleotide polymerization.

Discovery of DNA

As microscopes started to become more sophisticated and provide greater magnification, the role of the nucleus in cell division became fairly clear. On the other hand, there was the common understanding of heredity as the ‘mixing’ of maternal and paternal characteristics, since the fusion of two nuclei during fertilization had been observed.

However, the discovery of DNA as the genetic material probably began with the work of Gregor Mendel. When his experiments were rediscovered, an important implication came to light. His results could only be explained through the inheritance of discrete particles, rather than through the diffuse mixing of traits. While Mendel called them factors, with the advent of chemistry into biological sciences, a hunt for the molecular basis of heredity began.

Chemical Isolation of DNA

DNA was first chemically isolated and purified by Johann Friedrich Miescher who was studying immunology. Specifically, he was trying to understand the biochemistry of white blood cells. After isolating the nuclei from the cytoplasm, he discovered that when acid was added to these extracts, stringy white clumps that looked like a tufts of wool, separated from the solution. Unlike proteins, these precipitates went back into solution upon the addition of an alkali. This led Miescher to conclude that the macromolecule was acidic in nature. When further experiments showed that the molecule was neither a lipid nor a protein, he realized that he had isolated a new class of molecules. Since it was derived from the nucleus, he named this substance nuclein.

The work of Albrecht Kossel shed more light on the chemical nature of this substance when he showed that nuclein (or nucleic acid as it was beginning to be called) was made of carbohydrates, phosphates, and nitrogenous bases. Kossel also made the important discovery connecting the biochemical study of nucleic acids with the microscopic analysis of dividing cells. He linked this acidic substance with chromosomes that could be observed visually and confirmed that this class of molecules was nearly completely present only in the nucleus. The other important discovery of Kossel’s was to link nucleic acids with an increase in protoplasm, and cell division, thereby strengthening its connection with heredity and reproduction.

Genes and DNA

By the turn of the twentieth century, molecular biology experienced a number of seminal discoveries that brought about an enhanced understanding of the chemical basis of life and cell division. In 1944, experiments by three scientists, (Avery, McCarty and McLeod) provided strong evidence that nucleic acids, specifically DNA, was probably the genetic material. A few years later, Chargaff’s experiments showed that the number of purine bases in every DNA molecule equaled the number of pyrimidine bases. In 1952, an elegant experiment by Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase confirmed DNA as the genetic material.

By this time, advances in X-Ray crystallography had allowed the crystallization of DNA and study of its diffraction patterns. Finally, these molecules could be visualized with greater granularity. The data generated by Rosalind Franklin allowed James Watson and Francis Crick to then propose the double-stranded helical model for DNA, with a sugar-phosphate backbone. They incorporated Chargaff’s rules for purine and pyrimidine quantities by showing that every purine base formed specific hydrogen bond linkages with another pyrimidine base. They understood even as they proposed this structure that they had provided a mechanism for DNA duplication.

In order to visualize this molecule, they built a three-dimensional model of a double helical DNA, using aluminum templates. The image above shows the template of the base Thymine, with accurate bond angles and lengths.

The final model built by Watson and Crick (as seen above) is now on display at the National Science Museum in London.

Quiz

1. Which of these statements about DNA is NOT true?

A. In eukaryotes, DNA is present exclusively in the nucleus

B. DNA is the genetic material for some viruses

C. DNA replication is semi-conservative

D. None of the above

2. Which of these scientists designed an experiment to show that DNA replication was semi-conservative?

A. Meselson

B. James Watson

C. Linus Pauling

D. All of the above

3. Why was the rediscovery of Mendel’s experiments important for the development of molecular biology?

A. Mendel’s experiments suggested that DNA was the hereditary material

B. Mendel’s laws of inheritance suggested that there were discrete biochemical particles involved in heredity

C. Mendel’s experiments with pea plants gave molecular biologists a useful model organism

D. All of the above

References

- Alberts, Bruce, et al. (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell, 4th. ed. Ch. 4. Garland Science: New York. ISBN: 978-0815316206.

- Lodish H, et al., (2000) Molecular Cell Biology. 4th ed. W. H. Freeman: New York. ISBN-10: 0-7167-3136-3.

- Nobel Media AB (2014) “The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1910” Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 10 May 2017 from http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1910/