Cloaca Definition

A cloaca is an orifice through which urine and feces are eliminated in birds, reptiles, amphibians, and a few branches of the mammal family tree. It also serves a reproductive function like the vagina in females of these species, and also performs the function of sperm ejaculation in males of some species.

The term cloaca comes from the Latin verb “cluo,” for “to cleanse.” Cloaca is a noun form which could be translated to mean “cleansing place,” “drain,” or “sewer.” That is fitting for its role as the exit point for urine and feces.

For females of species who have cloaca, it is where males deposit sperm. In some species – most birds, for example – both males and females use their cloacas to mate. Most birds mate by having their cloacas “kiss,” during which time sperm is transferred from the male’s cloaca into the female’s. Only a few birds – mostly ducks and swans – have penises instead of cloacas.

The use of three separate orifices for these purposes (the urethra, anus, and vagina) is a fairly new evolutionary adaptation. Only placental mammals have these three orifices. Older mammal lineages like monotremes, tenrecs, golden moles, and marsupial moles have cloacas like their reptile ancestors have cloacas like amphibians, reptiles, and birds.

Interestingly, most fish do not have cloacas: sharks, rays, and lobe-finned fishes do, but most fish have a separate anus. That suggests that the anus evolved at least twice independently: once in fish, and once in mammals.

Cloaca Function

The cloaca serves as a waste-elimination point for both urine and feces. In animals with cloacas, both the intestinal and urinary tracts end at the cloaca. This makes it the animal’s all-purpose waste-elimination site.

The cloaca also serves the function of the vagina in females, and in some species serves a function similar to that of the penis in males. Female animals with cloacas receive sperm, lay eggs, and give birth through their cloacas.

In some species, males secrete sperm through their cloacas, and mate by having the male and female cloacas “kiss” so that sperm transfer can occur. However, this is not universal: some cloaca-possessing species also have penises.

Some species also have truly unique uses for their cloacas.

Some species of amphibians, reptiles, and mammals are thought to have glands in or near their cloacas which produce their distinctive, personal scent. These scent glands can be used to mark their territory and leave personal chemical messages, such as those used to advertise availability during mating season.

This is similar to the function performed by glands near the anus in some mammals such as dogs.

Some animals can actually breathe through their cloaca! This is an extension of an ability called “cutaneous respiration,” in which the skin can be used to absorb oxygen and release carbon dioxide just like the surface of the lungs. Lungs are more efficient, as they are designed to maximize air flow and blood/oxygen transfer. But for some species, other body surfaces can be important sources of respiration.

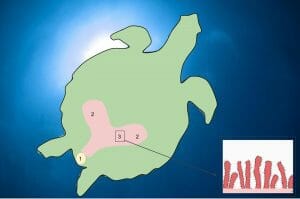

Some turtles, for example, have specialized “air bladders” connected to their cloacas. This allows them to take in air through the cloaca, store it in these air bladders, and use it as a source of oxygen while they are diving under water.

A diagram of a turtle’s cloacal air bladders can be found below:

Gila monsters, doves, and possibly other animals can use their cloacas to cool their bodies in hot environments. Scientists first noticed this because the gila monster – a desert lizard – can actually inflate its cloaca and cool its body through cloacal evaporation. This species, which does not have sweat glands in its skin, can essentially “sweat” through evaporation of moisture from its cloaca.

Scientists wondered if birds could do the same thing, so they decided to test for it by measuring heat loss and cloacal moisture in birds kept at high temperatures.

Sure enough, one test found that the doves studied appeared to secrete more moisture through their cloacas under very high-temperature conditions, and were able to achieve heat loss this way. However, it appears that not all birds can do this; the Eurasian quail, when tested, did not see the same effect.

Scientists are now studying to learn whether other animals might do the same thing!

The most important roles of the cloacas are as the site of waste elimination, and the site of reproductive activity. Without those functions, any species would be in very big trouble!

But the more scientists study the animal kingdom, the more they learn that our cousins can have some truly surprising biological innovations, such as taking advantage of the cloaca in surprising ways!

Quiz

1. Which of the following animals would you NOT expect to have a cloaca?

A. A lizard

B. A parakeet

C. A dog

D. A shark

2. Which of the following is NOT a use for the cloaca?

A. Exit point for urine and feces

B. Site of sexual reproduction

C. Site of temperature regulation for some lizards and birds

D. None of the above

3. What can we tell from the fact that most fish have separate anuses, but amphibians, reptiles, birds, and some mammals do not?

A. Since more animals have cloacas than separate anuses, cloacas must be the superior system.

B. Placental mammals must be directly descended from fish.

C. Separate anuses must have evolved at least twice: once in fish, and once in placental mammals.

D. None of the above.

References

- Romer, A. S., & Parsons, T. S. (1990). The vertebrate body. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publ.

- XHager, Y. (2007). Cloacal Cooling. Journal of Experimental Biology, 210(5), I-I. doi:10.1242/jeb.02737