Definition

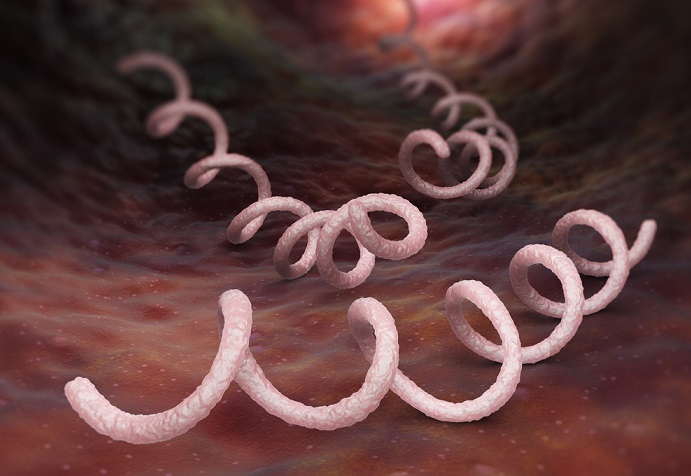

Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum is a subspecies of the Treponema genus and a microaerophilic bacterium that belongs to the spirochetal order. It is characterized by a thick phospholipid membrane and a very slow rate of metabolism, requiring approximately thirty hours to multiply; even so, T. pallidum is a difficult-to-eradicate pathogen and responsible for the sexually-transmitted disease, syphilis.

What is Syphilis?

Syphilis is a chronic human disease and the result of either sexual transmission or transmission from mother to baby during its progression along the birth canal.

Known as ‘The Great Pretender’ has a differential diagnosis is always possible, the first potentially visible sign of syphilis is the chancre, a small, round and hard ulcer or lesion found at the site of primary infection. As this site is often inside the vagina, mouth, throat or anus, a chancre is rarely detected immediately unless is it visible – on the lips or penis. Most internal primary lesions are observed at a later date during general screening activities in clinical settings. Poorer populations with low access to medical care are more likely to continue in sexual activity (and subsequent childbearing) without the benefit of diagnostics and treatment.

A chancre also heals without treatment after approximately one month. This is another reason why those without immediate access to medical care may ignore a primary syphilis lesion or discontinue antibiotic therapy. However, it is very important that treatment commences at the primary phase to prevent a syphilis infection from reaching the secondary phase.

The secondary stage of syphilis is characterized by a rough red or brownish rash usually on the soles of the feet and the palms of the hands, although the location can be elsewhere on the body. Another secondary syphilis symptom is the appearance of larger lesions in moist areas such as armpits, mouth, and groin. These lesions are known as condyloma lata. Again, if treatment is ignored, the secondary phase of syphilis will progress to a further stage. Additional worrying symptoms associated with the secondary stage include hair loss, swollen glands, headaches, and fatigue. Consultation with medical professionals is, therefore, more common during this phase.

The next stage of syphilis development is the latent stage. It presents without symptoms and its name – latent – refers to a dormant period; however, Treponema pallidum is still present within the body and the person in question remains highly infectious when taking part in sexual activities with one or more partners. This is also possible when an infected female gives birth to a baby without a caesarian section. The latent stage can last for many years but the latent stage’s symptom-free characteristics discourage carriers to seek out medical help.

Without treatment, the latent stage of syphilis eventually passes into a potentially fatal tertiary syphilis. Colonization of T. pallidum in various areas of the anatomy will cause serious damage. Diagnosis often names a tertiary stage according to the area of damage, in particular neurosyphilis, cardiovascular syphilis, and ocular syphilis. Other areas of damage are the liver, bones, and joints. Lesions and open sores progress over the body. It is because of this tertiary stage that the disease was given its name as ‘The Great Pretender’; multiple diagnoses exist for the symptoms also produced by a T. pallidum infection of the tertiary stage.

Upon initial contact with this spirochete, infected humans develop specific immune responses that do not have the capacity to wipe out large populations of treponemes from syphilis sites. Usually, T-cell-mediated delayed-type hypersensitivity responses involve the infiltration of T-cells into Treponema inoculation sites and activate macrophages to remove these treponemes via phagocytosis. However, T. pallidum bacteria can avoid this hypersensitivity response thanks to a number of factors.

Treponema Pallidum Immunity Factors

Treponema pallidum immunity factors are a complicated affair that has made it very difficult to develop a vaccine. A lack of knowledge pertaining to the occurrence of multiple reinfections in humans, even after a strong immune response during the first infection, means a cure has not yet been found. Recent research into the protective mechanisms of these so-called stealth pathogens is, however, a hot topic; new discoveries are regularly published in scientific journals.

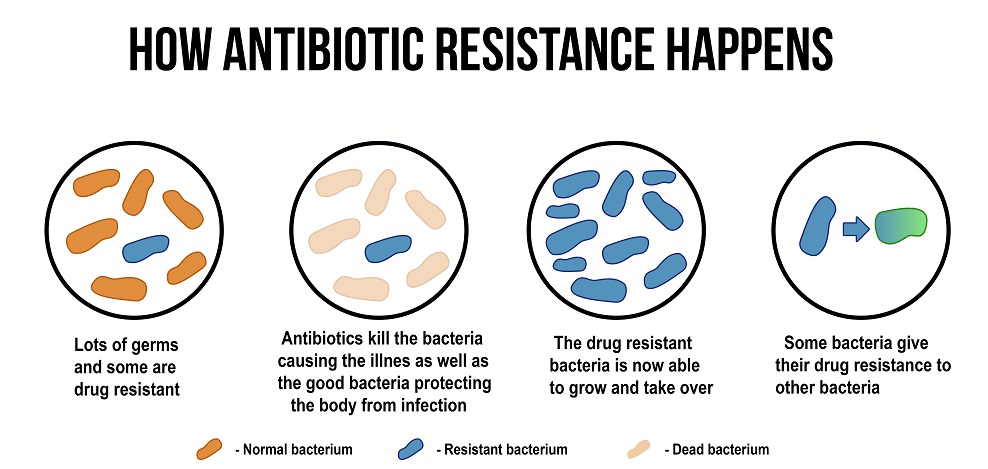

T. pallidum transmits syphilis through vaginal, anogenital, and orogenital contact. This bacterium has an extremely small genome and lacks genes that encode the classic virulence factors of more aggressive and resistant bacteria. This means that treatment with penicillin is very effective. However, current ideology regarding an antibiotic-resistance crisis, the increasing number of allergic reactions to penicillin in the human population, and the rapid reappearance of syphilis around the globe cause concern.

Studying Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum is made more difficult through the susceptibility of these bacteria to in-vitro settings; it is very hard to reproduce colonies in a laboratory. A more recent understanding of T. pallidum subsp. pallidum metabolism is now enabling some researchers to succeed where others have failed.

The combination of small genome, very slow metabolism and thick phospholipid membrane makes this spirochete a power-packed disease carrier in an extremely basic package that has been grouped into a small group of difficult to immunologically recognize and remove microorganisms known as stealth pathogens. Treponema can survive quietly in the human body for years and at the same time remain highly infectious.

Treponema Pallidum: Stealth Pathogen

IgG Treponema pallidum protection in the form of immunoglobulin G antibodies – the most common type of antibody in human blood and other extracellular fluids – is a later response to infiltration by a foreign organism or material than IgM (immunoglobulin M antibodies). In the case of T. pallidum subsp. pallidum, primary infection of a previously non-infected human occurs during sexual activity or natural birth. T. pallidum bacteria pass from an infected person into a new human host and slowly multiply.

In order to understand T. pallidum’s identification as a ‘stealth pathogen’, it is first important to understand the mechanisms involved in its recognition as a hostile protein and the body’s inefficiency in removing it.

The Treponema Reduced Immune Response

A protein foreign to the body is referred to as an antigen. The majority of bacteria, viruses and other pathogens produce antigens on their surface membranes which are usually instantly recognized as foreign. In the case of T. pallidum, the thick phospholipid membrane holds the majority of these antigens hidden under its surface. Furthermore, the membrane lacks lipopolysaccharide (LPS) glycolipids. LPS’s cause inflammatory Gram-negative bacteria reactions that either alert the immune system to act or cause symptoms that bring the infected person to request medical help. This combination of features means that Treponema pallidum enters the body without attracting much attention and, even though it multiplies slowly, is given the time to disseminate (spread) with little resistance.

The chancre is, therefore, a sign that the innate mechanism of active immunity has detected a foreign presence and proceeded to attack it. Macrophages that recognize the few Treponema surface proteins as hostile begin to remove them via phagocytosis (see below). As foreign bacteria are broken down, large amounts of inflammatory cytokines are produced. The result of this initial inflammatory reaction is the chancre. This initial response is quite late and the body is by now the host of T. pallidum spirochete colonies.

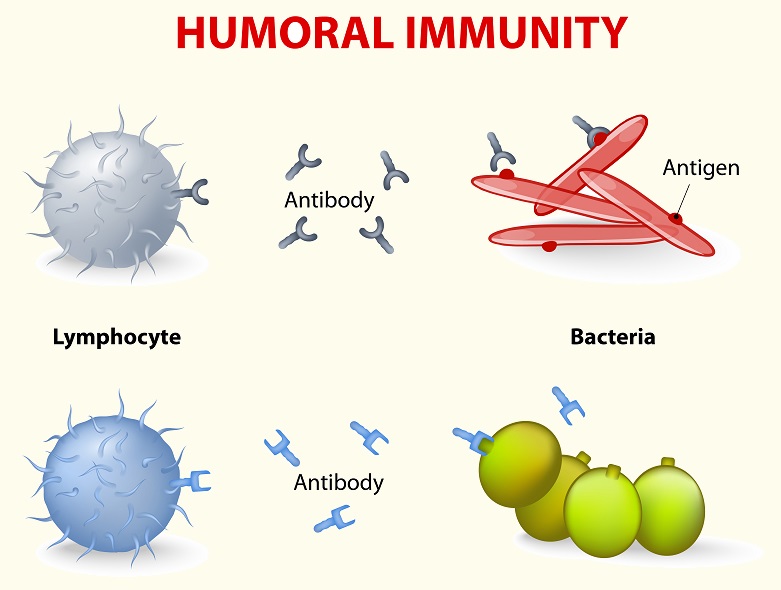

Macrophages show the results of their work to B lymphocytes or plasma B cells that begin the process of somatic hypermutation in the adaptive (or humoral) immune system – a process that allows the B cell to set up a code for a new antibody. This code is featured on the antigen as a Treponema pallidum-specific binding site (Antigen Binding Site or ABS). Immunoglobulin M is one of the first-produced antibody types; immunoglobulin G is the most commonly formed.

The new antibodies circulate and recognize the coded T. pallidum bacteria surface proteins wherever these are visible and set to work destroying the bacteria. How effective this action is may have an effect upon the length of the latent stage of syphilis and the appearance and severity of tertiary symptoms.

More recent data, however, complicates this later recognition process. Forms of T. pallidum are heterogeneous, meaning diverse types exist within a single subspecies. For bacteria with one of the smallest genomes known to man, this is no small feat. While one form of the hostile bacteria will bind with the antigens produced by the adaptive immune system, another form will not. Additionally, the antigen-to-antibody binding process is significantly slow, almost keeping the immune system distracted and leaving non-binding versions to multiply and spread. The inflammation resulting from the destruction of binding T. pallidum causes secondary symptoms such as palm and sole rash and condyloma lata. The energy required to keep populations of spirochetes under control leads to fatigue. The theory that spirochetes may colonize hair follicles may be pertinent to hair loss in secondary syphilis.

Treponema Pallidum and IgM

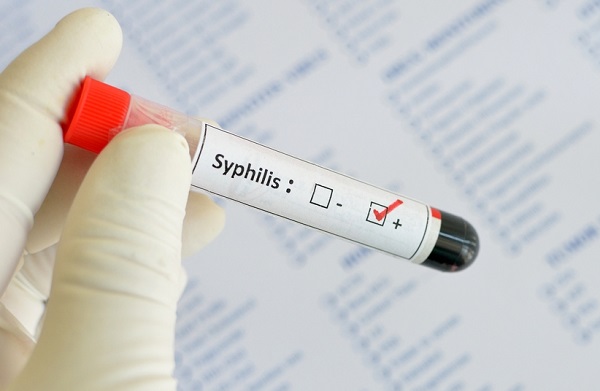

Treponema pallidum IgM response at initial infection is, as has already been described, slow and hindered through a difficult to recognize bacterial membrane. This means that IgG responses very quickly follow that of IgM; testing solely for IgM antibodies as a method of detecting early Treponema infection is of little diagnostic value. Instead, blood serum testing for syphilis by way of an antibody test is carried out with Total Antibodies (IgG and IgM) testing.

Testing Treponema Pallidum Antibodies

To test Treponema pallidum antibodies, all that is needed is a few milliliters of blood collected in a tube that separates blood serum from the cell mass. The antibody test known as Syphilis Total Antibodies has relatively recently taken over the pole position of an older test known as RPR or Rapid Plasma Reagin. Previously, RPR was advised as an initial test to determine the presence of cardiolipin, cholesterol, and lecithin in blood plasma. These are non-specific antibodies produced when a body is fighting certain sorts of bacterial or viral infection via adaptive immunity. A doctor would, therefore, have to first observe syphilis symptoms or consider a person at risk of syphilis before justifying such a generic test. Only if the result of an RPR came back positive in an at-risk patient or one showing symptoms would a Syphilis Total Antibodies (STA) test be requested.

The table has since been turned. The first test is now the Syphilis Total Antibodies (STA) test. If this comes back negative, there is little need for the RPR. If the physician is not convinced or if more results are requested, the RPR can provide further proof of antibody activity. If there is a discrepancy between STA and RPR results, a further test called T. pallidum particle agglutination (TPPA) will confirm a positive or negative result.

Quiz

1. In which order would you carry out the following tests?

A. RPR, TPPA, STA

B. IgM, IgG, RPR

C. ABS, RPR, STA

D. STA, RPR, TPPA

2. Which of the following is not a symptom of secondary syphilis?

A. Rash on palms and soles

B. Chancre

C. Condyloma lata

D. Fatigue

3. Which of the following products found on Gram-negative membranes cause inflammatory reactions?

A. T-cells

B. ABS

C. LPS

D. IgM