Definition

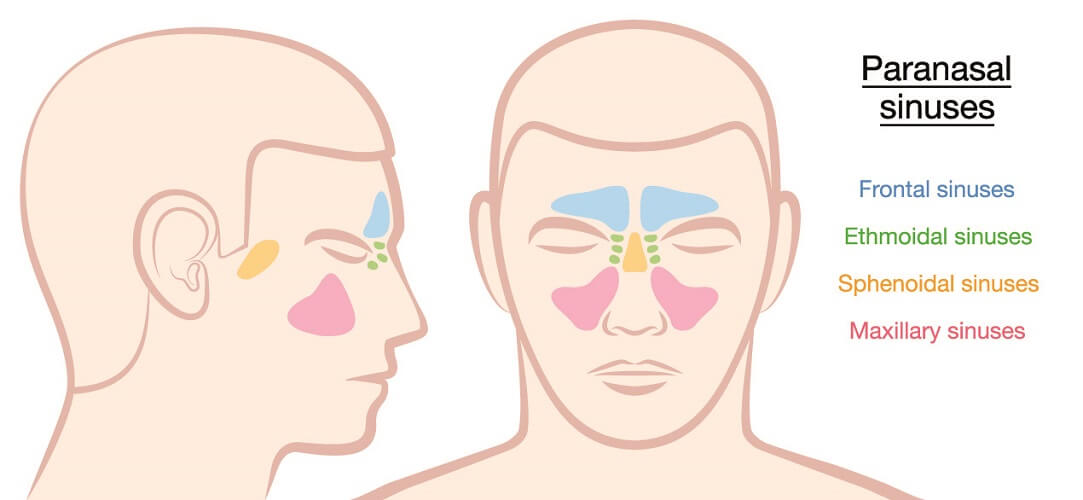

The paranasal sinuses are four pairs of hollow cavities in the facial and cranial bones. They are located at the center of the face, surrounding the nose (paranasal). Paranasal sinuses function as air-warming cells and help to defend the airway against pathogens. Theories also list other functions such as reducing total skull weight and changing vocal tone, although these are not primary roles.

What are the Paranasal Sinuses?

The paranasal sinuses are four paired, hollow areas within the frontal bone, maxillary bones, ethmoid bone, and sphenoid bone. Sinuses are sometimes referred to as air cavities. The four paranasal sinuses surround the nasal cavity and are lined with epithelium and mucus-producing cells. All paranasal sinuses open into the nasal cavity.

Every time we breathe through our noses, air is pulled into the nasal cavity; a proportion of this air enters the paranasal sinus cavities.

Humans have four paired paranasal sinuses:

- Frontal sinus – fans out from the bridge of the nose to the lower forehead

- Maxillary sinus – fans out from the inner corners of the eyes to the cheek

- Ethmoidal sinus – behind the lower eye socket and above the nasal cavity

- Sphenoidal sinus – at the back of the nasal cavity, close to the pituitary gland

Paranasal Sinuses: Anatomy

Paranasal sinus anatomy is simple – they are hollowed-out areas of bone lined with a layer of cells.

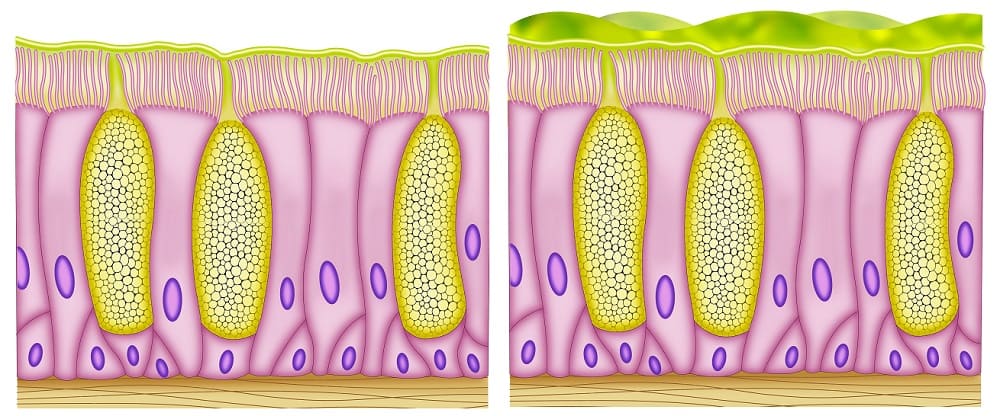

The surrounding bone is covered with a layer of pseudostratified (columnar) ciliated epithelium; this sheet of cells also contains goblet cells (mucus-producing cells). The cilia help to move mucus into the nasal cavity.

The paranasal sinuses develop at different times. At birth, human babies already have paired maxillary and ethmoid sinuses. The frontal sinus is usually present by the age of five but does not fully develop until the teenage years; up to 10% of people do not have a frontal sinus. The sphenoid sinus does not develop until adolescence.

All paranasal sinuses drain into the nasal cavity. This can be via ostia (small holes), gaps between bony compartments, or clefts. The maxillary and sphenoid sinuses exit into the nasal cavity by way of ostia; the ethmoid sinuses contain multiple tiny air pockets (air cells) and drain via the gaps between these cells. The frontal sinus drains through the frontal recess, an inverted funnel-shaped channel.

All mammals have paranasal sinuses, although not all mammals have four. Paranasal sinuses in dogs number just three – the frontal and sphenoidal sinus, and the maxillary recess. Rabbits do not have frontal or ethmoidal sinuses but a dorsal conchal sinus, maxillary sinus, and sphenoidal sinus.

What Are the Functions of Paranasal Sinuses?

Paranasal sinus function is still a matter of debate. Their proximity to the brain, eye, nose, and mouth has produced countless theories. These range from making the skull lighter, providing a means of filtering, humidifying, and warming inspired air, structures that contribute to our immunity, and even a way of making our voices louder.

Not all paranasal functions are positive. They are linked to the transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, providing the ideal environment for virus proliferation. While the sticky mucous membranes of the paranasal sinuses have been designed to capture pathogens and bring in white blood cells to destroy them, new viruses have more time to multiply. This seems to be the case with COVID-19.

One way to know what the functions of paranasal sinuses are is to observe people who don’t have them. Total paranasal sinus aplasia, an uncommon occurrence where all four paired sinuses are absent, gives us an idea of the main purpose of healthy sinuses.

In this rare report, the two patients with total paranasal sinus aplasia being discussed by specialists seemed to have very few physical complaints – one only reported a feeling of fullness in the face; the other suffered from regular headaches and pain when chewing. Neither suffered from recurrent sinus infections.

Paranasal Sinuses: Immunity

The paranasal sinuses are heavily associated with both the innate and adaptive immune systems. However, as we have just seen, the few adults with total paranasal sinus aplasia that have been studied did not complain of recurrent infections. The nasal cavity might be able to cope with this task alone; the paranasal sinuses serve as a backup.

Innate immunity is the type of immunity we are born with. Our skin, stomach acid, tears, the blood-brain barrier, and mucus are all examples of the innate immune system. Processes such as inflammation caused by damaged cells and the body’s tiny army of waste disposal units (phagocytes, natural killer cells, mast cells, innate lymphoid cells, eosinophils, and basophils) are all part of this initial response to an attack.

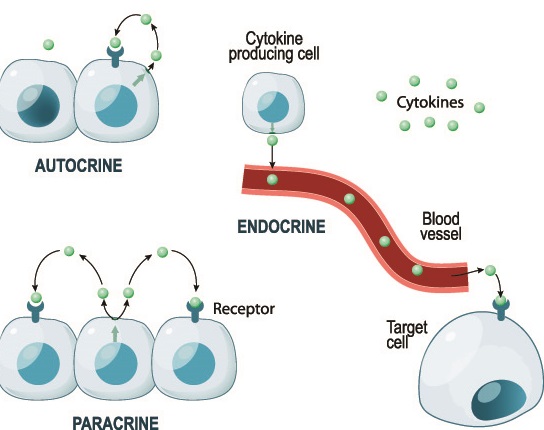

Usually, the paranasal epithelium cells are packed in rows with no gap between them. This creates a barrier. In people with chronic rhinosinusitis (continuous infection of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses), the junctions between these cells are not as tight. If pathogens get through the protective epithelium they trigger responses from certain types of white blood cells. These cells release inflammatory cytokines.

Not only the epithelium but also the watery mucus produced by goblet cells are part of our innate immunity. Mucus traps antigens (foreign particles). A sneeze or blowing your nose removes them.

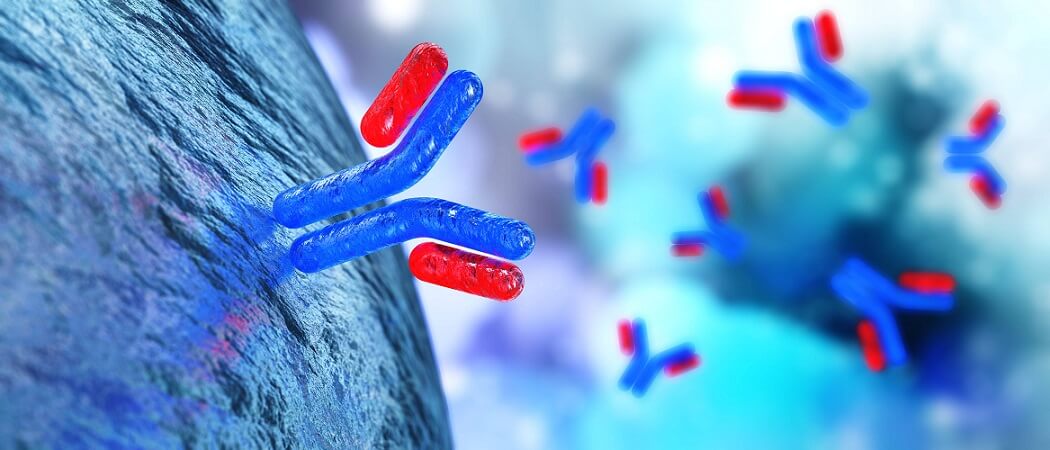

The adaptive immune system or acquired immune system refers to another role of the paranasal sinus epithelium. Acquired immunity involves the production of antibodies. Adaptive immune cells such a T cells and B cells learn to recognize specific foreign particles and produce or help to produce antibodies. Antibodies stick to pathogens and mark them for destruction.

The paranasal sinuses, together with the nasal cavity, play a role in protecting the airway from viral, bacterial, and fungal infection. The epithelium hosts nasal dendritic cells that absorb foreign microbes and present them to T cells, initiating an immune response.

Air Warmth and Humidity

It is estimated that the average human (carrying out normal daily activities) breathes in around seventeen kilograms (14,000 liters) of air per 24 hours. The body uses energy to warm and humidify this air; air reaching the lungs should be approximately the same as body temperature and contain around forty grams of water per kilogram. If too cold or hot, the lungs can become damaged.

On a warm (but not hot) day, a human will use around 250 calories to heat and humidify dry air over the period of twelve hours. In very low temperatures of -22°F (-30°C), the body uses up to ten times this amount. This means that the paranasal sinuses save us a lot of energy.

The total volume of all four paired paranasal sinuses is around 90 cm3 in adult males and 70 cm3 in adult females. The average volume of air we breathe in (tidal volume) is about 500 cm3. So healthy paranasal sinuses warm and humidify about 15% of the air we breathe, saving calories that would be otherwise be used to bring the respiratory system back to body temperature whenever we breathe in cold, dry air.

Skull Weight

Many sources say that the paranasal sinuses of the skull reduce bone weight. However, studies show that the weight of bone replaced by these hollow spaces is not significant at all – between two to three ounces or 55 to 85 grams.

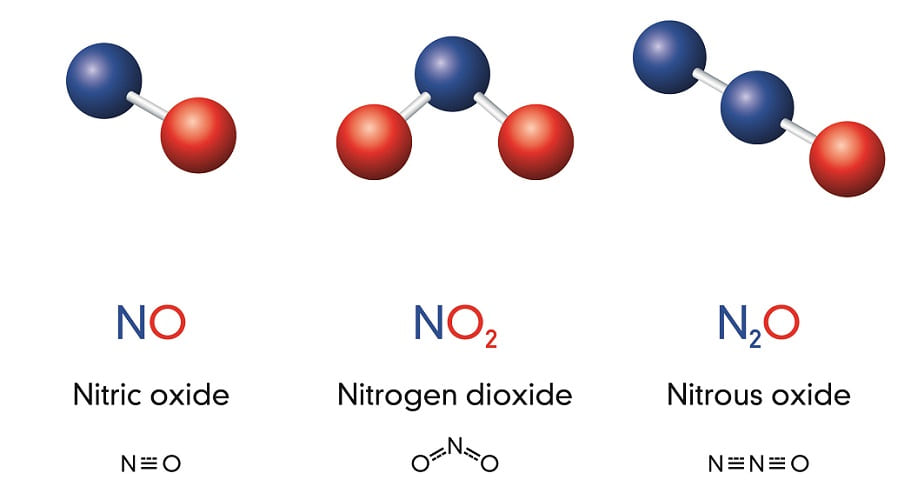

Nitric Oxide Production

In the past decade, researchers have discovered that the epithelium of the paranasal sinuses can produce nitric oxide gas. Nitric oxide not only kills microbes but also dilates the blood vessels. Low levels of paranasal sinus nitric oxide have been found in people suffering from chronic rhinosinusitis.

When this nitric oxide travels to the lungs, it widens the local blood vessels and improves oxygen uptake.

Vocal Resonance

Much research has been done on the effect of the paranasal sinuses on vocal resonance. Resonance refers to the intensity of the voice. Tests on cadavers (that neither speak nor sing) do not support this theory. Other studies report that the maxillary sinuses have a limited effect upon vocal tone.

Paranasal Sinuses: Disease

There are two types of paranasal sinus disease: sinusitis and mucoceles.

Sinusitis (rhinosinusitis or sinus infection) is most commonly the result of a cold. Viruses entering the nasal cavity produce tissue swelling (inflammatory response). Inflammation can block one or more sinuses from draining into the nasal cavity. The affected cavities fill with mucus and produce pressure headaches.

Paranasal sinus mucosal thickening could be an indication of mucoceles. Mucoceles are mucus-filled cysts caused by sinus blockages. Also called sinus cysts, mucoceles grow slowly and can also affect the surrounding bone. Because a mucocele will continue to grow in size, it should be endoscopically removed.

Paranasal Sinuses: Cancer

The most probable site of paranasal sinus cancer is the maxillary sinus.

The bone, the cells that line the sinus, and the cells that defend the body at the paranasal sinuses have the potential to become malignant tumors.

Most paranasal sinus cancer cases are squamous cell carcinomas (of squamous epithelial cells). When mucus-producing cells of the epithelium (goblet cells) mutate, they may form adenocarcinomas. The white blood cells that defend our bodies against pathogens have the potential to form paranasal sinus lymphomas. Should the bone cells surrounding the sinus cavity mutate, the resulting tumor is a sarcoma.

Fortunately, paranasal sinus cancer is rare. Approximately 2,000 people in the US will develop this disease per year, most of them males over the age of 55.