Definition

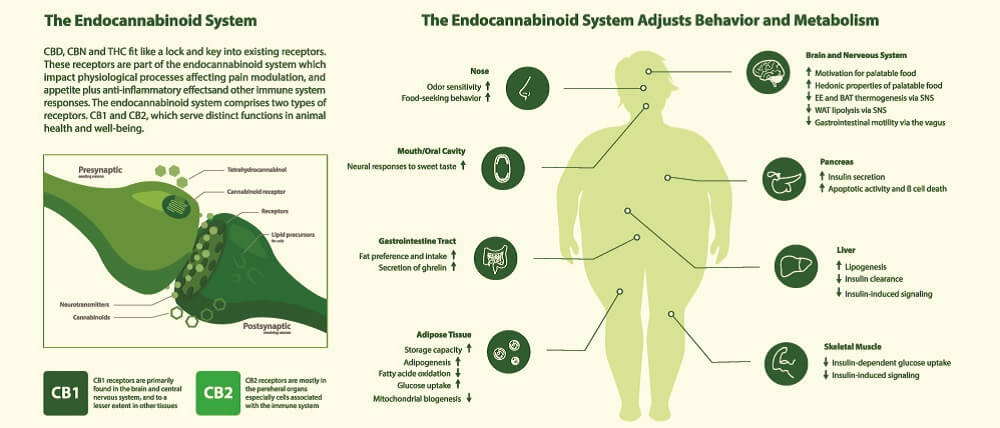

The endocannabinoid system utilizes lipids called cannabinoids and cannabinoid receptors to affect certain sensory responses and behavior. This system is commonly recognized as the pathway network that produces the effects caused by psychoactive components in cannabis. However, research in the field of CBD oil is showing a greater role in nerve transmission. This system is a central nervous system signaling network; its mechanism is linked to how our brain and body cope with physical and emotional stress. The endocannabinoids are produced by the body also act as metabolic and immune effectors.

What is the Endocannabinoid System?

The human endocannabinoid system (ECS) has come under much scrutiny in recent years due to the CBD oil business – the non- or low-psychoactive supplement said to improve a range of mental and physical disorders.

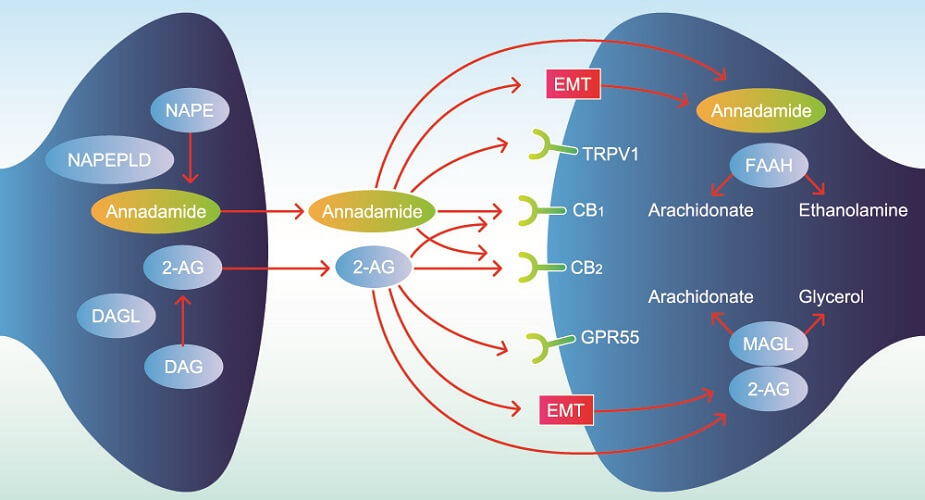

This system involves endogenous cannabinoids (endocannabinoids), their receptors, and the enzymes that break down endocannabinoids into smaller molecules. We have only begun to learn about the various pathways within this system and, since the 1990s, have been slowly unraveling how it works.

The Endocannabinoid System Explained

Endocannabinoid system 101 describes a negative feedback mechanism. This mechanism helps to regulate certain body systems and so maintain internal homeostasis or steady states, much of this in the brain. Systems affected by the ENS are associated with:

- Pain

- Sleep

- Mood

- Memory

- Learning

- Inflammation

- Immune

- Energy

- Coordination

- Hunger

- Temperature

For example, when the body experiences pain, endocannabinoid system function helps to reduce this sensation. When neurotransmitter imbalances make us feel unhappy, endogenous cannabinoids try to bring the mood back to a more neutral state. Some endocannabinoid receptors work at gut level to improve digestion, others in tissues throughout the body to mediate inflammatory reactions.

Endogenous Cannabinoids

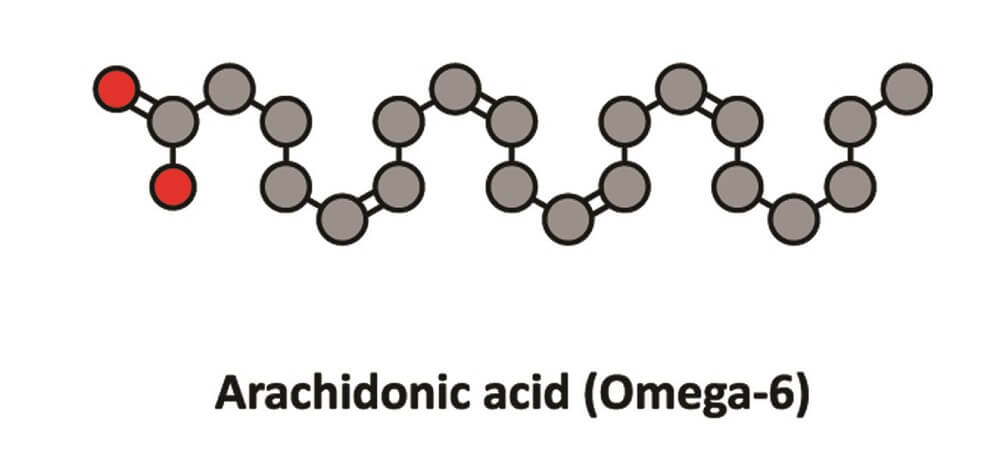

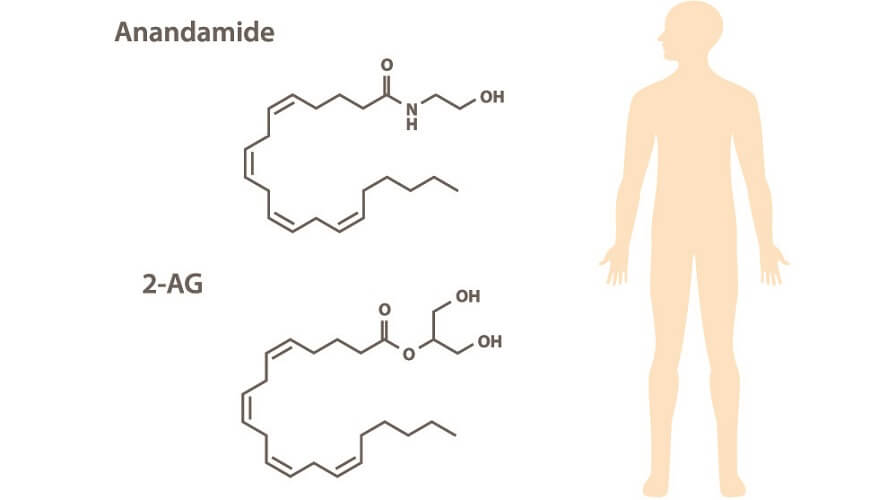

Endogenous cannabinoids – as the word endogenous suggests – are produced in the body. Also called circulating endocannabinoids, these are synthesized in different cells of the brain, muscle, and fat tissue, and in circulating cells that travel through the bloodstream and lymph vessels. Two main endocannabinoids exist; both are formed from arachidonic acid (omega-6) and are categorized as signaling lipids:

- N-arachidonoylethanolamine (AEA)/anandamide (ANA)

- 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG)

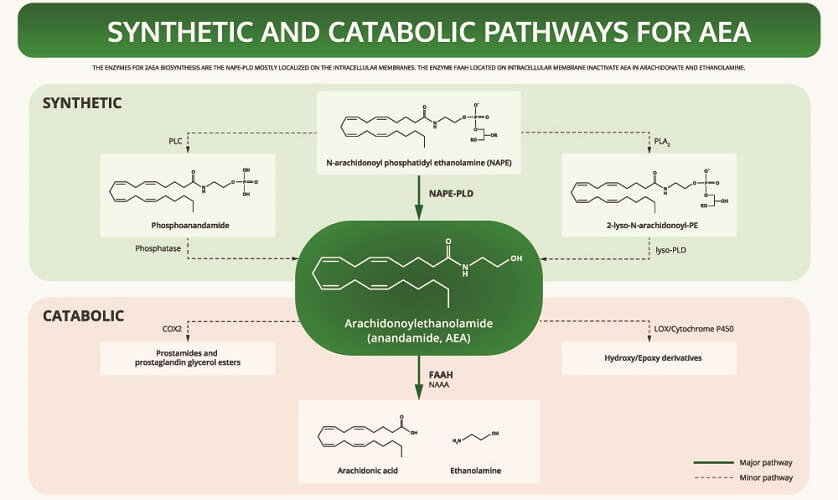

AEA is synthesized from a phospholipid commonly referred to as NAPE. It is a fatty acid neurotransmitter that does not exist for long after it has been produced by certain cells. We should, therefore, have a consistent level of omega-6 fatty acids in our bodies.

To understand how anandamide affects the body, we can look at the story of Jo Cameron from Scotland. Her inability to feel pain is due to a genetic mutation in the FAAH gene. This gene produces the FAAH enzyme that breaks down circulating anandamide and so reduces AEA availability. Jo’s mutated gene produces very low quantities of FAAH. When levels of anandamide are high, they produce an analgesic effect – the brain does not process pain stimuli.

Furthermore, another sequence called the FAAH-OUT gene was also found to be mutated in this very interesting subject.

FAAH-OUT seems to regulate the FAAH gene. Jo has double the normal levels of anandamide due to a genetically-controlled lack of a specific enzyme and no ability to regulate its very low production rate.

Since childhood, Jo has been immune to pain. From breaking an arm when a child to unknowingly burning herself on the oven, she does not notice when she is injured. Jo also rates herself as an extremely upbeat and positive person.

Researchers have found that these two mutations regulate pain sensation, mood, and even memory. In Jo, the absence of anxiety and depression are, therefore, due to genetic faults in her endocannabinoid system that increase endocannabinoid availability. The receptors that bind to these endocannabinoids (and to exogenous cannabinoids, too) must be functioning well to produce their associated analgesic and mood-elevating effects.

Cannabinoid Receptors

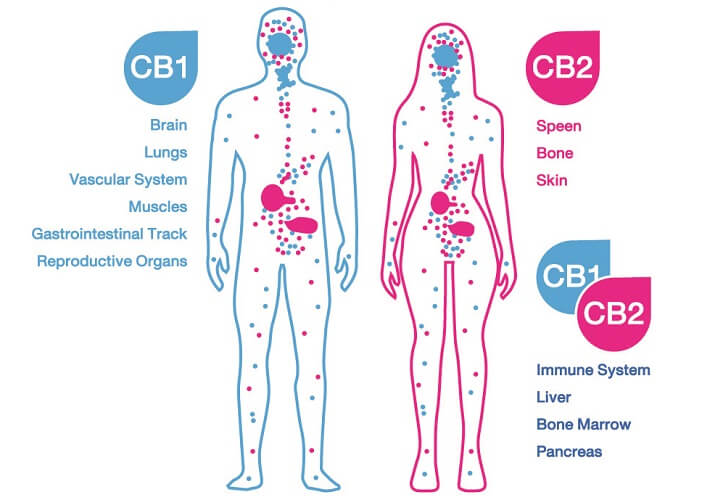

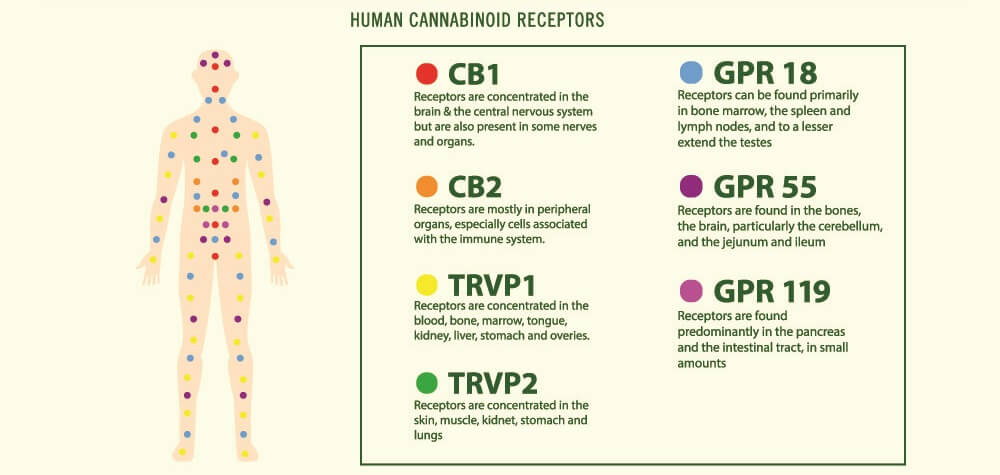

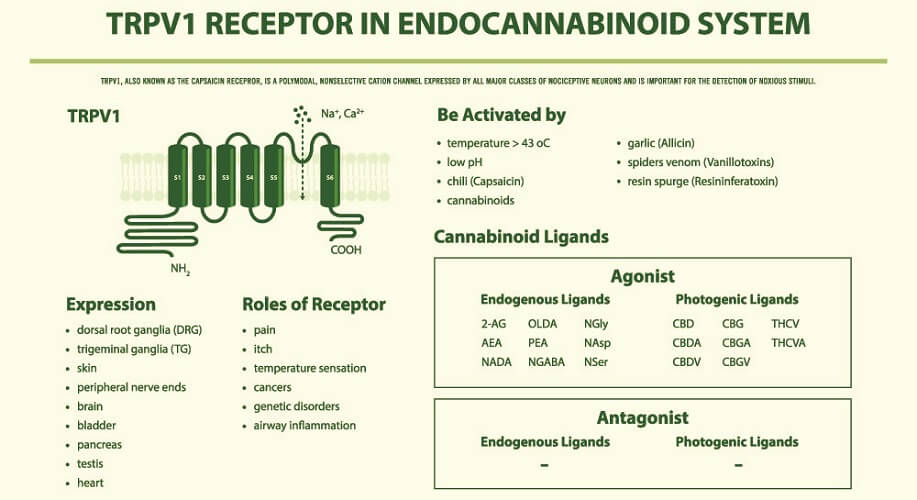

AEA and 2-AG bind to cannabinoid receptors. These are split into two groups – CB1 and CB2 (CB1R and CB2R). Both cannabinoids can also bind to and activate transient receptor potential cation channels (TRPs) and some G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs/GPRs) , while only AEA acts on several peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs). TRPs are primarily inflammatory regulators found throughout the body (subgroups thicken the gut mucosa to improve digestion, for example); GPRs have roles that encompass practically every body system – those affected by the ECS are now referred to as novel cannabinoid receptors; PPARs are most associated with glucose and lipid homeostasis, as well as inflammation pathways.

These additional receptors explain why many studies show that disorders such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and irritable bowel disease improve when exogenous cannabinoids are administered. However, as we as yet have limited knowledge of this system, the potential long-term side effects of endocannabinoid system therapies are also unknown.

The protein receptor known as CB1R was first discovered in brain cell membranes; it is found in much higher quantities in the central nervous system than CB2R. This first cannabinoid receptor exists in different forms. The longest – canonical – form is most prolific in the brain and skeletal muscle. Shorter chains called isoforms are primarily located in other organs such as the liver and pancreas. We still know very little about these shorter forms.

In the brain, most CB1 receptors lie in the olfactory bulb, hippocampus, basal ganglia, and cerebellum. Lesser amounts are found in the cerebral cortex, amygdala, and hypothalamus. They are also present in specific CNS cells – astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia. The prolific spread of receptors tell us very plainly that the endocannabinoid system is central to brain function.

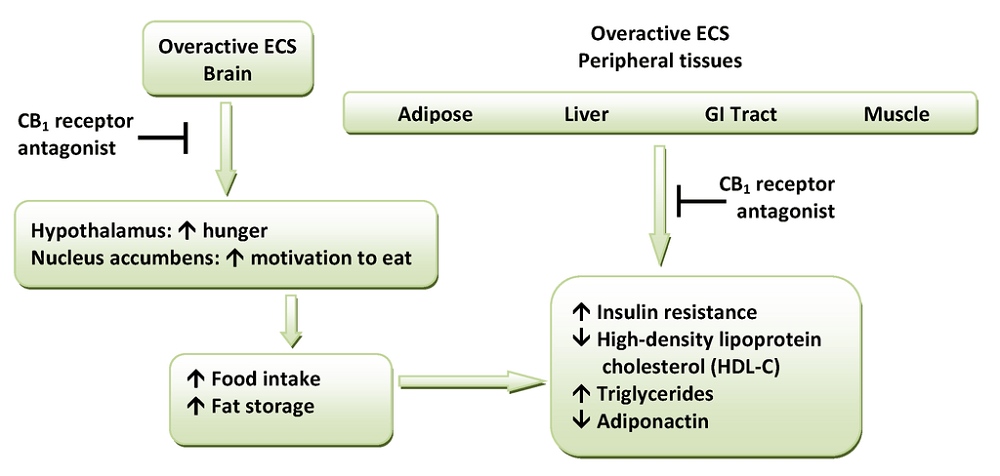

In peripheral tissues, CB1 receptors are also extremely important. So far, we know they affect how quickly we digest food, how leaky the gut is, how resistant to insulin we are, how healthy our hearts are, and how our body fights infection.

CB2R is very different from the first receptor type in form and has two known isoforms in human subjects. One of these is found in the testes of males and the other in the spleen. CB2 receptors are located in immunological tissues and cells, including white blood cells and the tonsils and thymus.

While CB1 receptors are the main endocannabinoid receptors in the brain, CB2 receptors also seem to play a crucial role here. The pathways in which CB2Rs are involved are neurological but also immunological. Both receptor types are also associated with inflammation and pain sensation.

Evidence is growing for the existence of CB3 receptors; however, this research is still very much in its infancy.

Damage or malfunction in both receptor types has been linked to various pathologies. These include learning disorders, schizophrenia, depression, glaucoma, epilepsy, stroke, appetite, and addiction. The system seems to be highly specific to certain neurological pathways; however, adjusting one pathway can lead to abnormalities in other endocannabinoid pathways as well as in other body systems. We certainly do not know enough about its interaction with other pathways to begin to produce medications based upon endocannabinoid system actions.

Exogenous Cannabinoids

Cannabinoids that enter the body from our environment and not produced via encoded sequences in our DNA are called exogenous cannabinoids. The most commonly quoted example of an exogenous cannabinoid is cannabis.

In the body, both endogenous and exogenous types bind to CB1 and CB2 receptors, as well as to the formerly-mentioned TRPs, PPARs, and GRPs.

An exogenous cannabinoid can be a medication, a supplement (cannabidiol oil), or a recreational drug (cannabis).

Endocannabinoid Deficiency

The new diagnosis of clinical endocannabinoid deficiency (CECD) is making headlines thanks to recent discoveries regarding a wide range of ECS-associated pathologies.

It has been suggested that multiple disorders that do not seem to be similar and have very different symptoms also seem to respond in a positive way to cannabinoid treatment. We know that, in many cases, the endocannabinoid system can help to treat digestion disorders, increase immunity, improve sleep, lift the mood, and regulate pain. From these observations, a new theory has come to light – endocannabinoid deficiency.

As with most endocannabinoid research, there is still much we don’t know. What is known is that certain pathologies are associated with too low or too high (compensatory) AEA and 2-AG levels:

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): low gastric AEA

- Fibromyalgia: low cerebrospinal fluid AEA

- Migraine: low serum AEA and 2-AG

- Multiple sclerosis: low cerebrospinal AEA and 2-AG

- Post-traumatic stress syndrome: low serum 2-AG and AEA

- Huntingdon’s disease: low numbers of CB1 receptors

In many of the above disorders and diseases, treatment with non-psychoactive components of cannabis (cannabidiol) often alleviates both the symptoms and that disorder’s progression. Even so, endocannabinoid system deficiency is not yet an accepted diagnosis in the medical sphere.

At the moment, such treatments could do more harm than good. It is obvious from research results that endocannabinoid system treatment is multi-faceted. The drug rimonabant was removed from circulation two years after being approved in Europe as a weight-loss medication due to side effects such as depression, anxiety, and even suicide.

This is one of the reasons why even the latest endocannabinoid system research produces such mixed results. The effects upon one system of exogenous cannabinoids depend on the ECS function of the individual, the characteristics of the disorder, and the presence of other imbalances. It is rare to achieve similar research results across the board when designing an endocannabinoid system therapy.

Endocannabinoid System and CBD

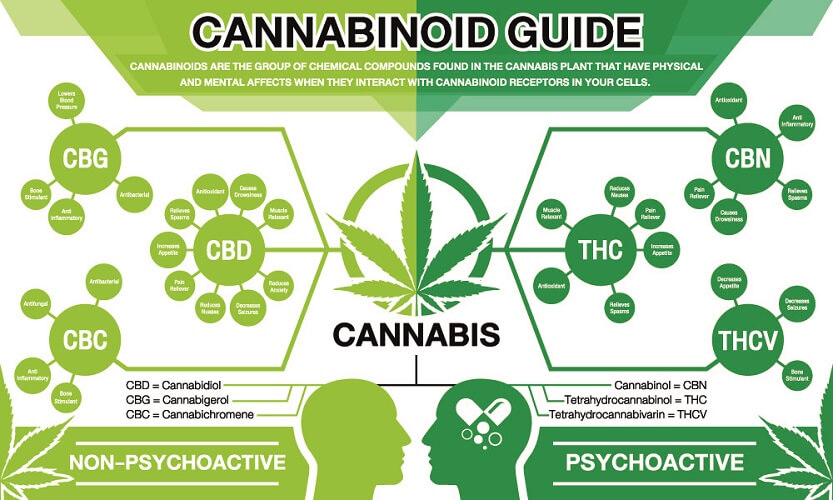

Cannabis sativa or marijuana is a controversial plant due to its psychoactive effects. It contains two main components – Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). While the former causes euphoria, the latter is not associated with this effect.

Furthermore, the cannabis plant contains approximately 111 other cannabinoids. Most studies look at cannabidiol and THC as these are present in much larger quantities.

As part of a regulating system, we know that Δ9-THC binds with CB1 and CB2 receptors and helps to produce the same effects as we saw in Jo Cameron – lower pain sensation and a positive mood. Cannabidiol does not bind to CB1 receptors unless Δ9-THC is present, making it an indirect agonist. THC also does not work alone – it is a CB-receptor partial agonist.

These exogenous cannabinoids also have very different effects. While THC increases dopamine-firing pathways (pleasure, reward, and motivation pathways), CBD does not. Instead, it seems that CBD inhibits the enzyme (FAAH) that breaks down AEA. By doing so, AEA levels increase. Just like with Jo.

Cannabidiol is more likely to bind to the other associated receptors than THC, although current studies give limited information. These include serotonin receptors that regulate disorders such as anxiety, addiction, and depression and transient receptor potential action cation channels (TRPs) that regulate pain and vasodilation levels. CBD also acts as an adenosine uptake inhibitor, helping to reduce inflammation and ensure a better night’s sleep.

What is important to know is, in the presence of Δ9-THC, endocannabinoid system CBD regulates the effects of the psychoactive cannabinoid. How this takes place is not fully understood but a recent drug has shown this effect very clearly.

In June 2018, the FDA approved Epidiolex, the first prescription medication to contain CBD. It is used for treatment-resistant forms of epilepsy.

However, early tests showed that any Δ9-THC administered to young epilepsy patients would lead to an increase in symptoms after a certain period. After a time, the positive effects faded and the disease progressed. If researchers can find where this switch-over occurs, this may be avoided in the future.

The endocannabinoid system and THC and the endocannabinoid system and CBD are two associated but separate pathways. It is too simple and too early to say that CBD regulates Δ9-THC effects; however, the signs are definitely there.