Definition

Erector spinae muscles or paraspinal muscles run vertically along the spinal vertebrae and work to stabilize the back from the lower sacral to the cervical vertebrae and enable spinal flexion, extension, and rotation. The erector spinae is not a single muscle but a group that consists of the spinalis, longissimus, and iliocostalis muscles deep in the back; these are further categorized according to their position – capitis (head), cervicis (neck), thoracis (thorax), and lumborum (lower back).

Erector Spinae Function

Erector spinae function is to stabilize the spine and allow us to make various types of movements that involve the spine. Where each muscle originates and attaches determines the range and direction of movement.

Other muscles of the back also help us to rotate, flex, and extend. Although the erector spinae are often called the deep back muscles, they are not the deepest. This is why you may see them labeled as intermediate muscles in anatomy books. The deeper muscle layer that lies underneath the erector spinae is a separate muscle group – the transversospinales muscles. They are mentioned in this article as they also play a part in movement but are definitely not part of the erector spinae muscle group.

The intermediate iliocostalis, intermediate spinalis, and intermediate longissimus muscles of the erector spinae (as they are also called) extend and lift the vertebral column to provide support. By separating the individual vertebrae they provide an extra layer of protection, keeping the small bones slightly apart and relieving pressure on the cartilage discs. One of the reasons we get smaller as we age is because of the thinning and stretching of these muscles – weaker, less dense bones and less distance between the vertebrae squashes the cartilage discs between them. If the erector spinae were in perfect condition throughout the aging process they would keep us closer to our original height.

The erector spinae also enable lateral flexion (bending sideways) and rotation of the back. Unilateral (one-sided) contraction of the erector spinae group causes the same side of the body to flex (ipsilateral flexion) or rotate, while bilateral contraction straightens or extends a portion of the spine. Pure erector spinae action is limited to flexion, rotation, and extension.

However, as has already been said, even deeper muscles help these movements – the transversospinales. Transversospinales allow for extension and contralateral (opposite side) rotation of the vertebrae, rib elevation to help us breathe, and an extra layer of spinal column stabilization. They have another role that the erector spinae do not – the rotatores muscles that are part of the transversospinales group contribute to proprioception – they let our brains know what position we are in and help regulate our posture, coordination, and balance.

Erector Spinae Group

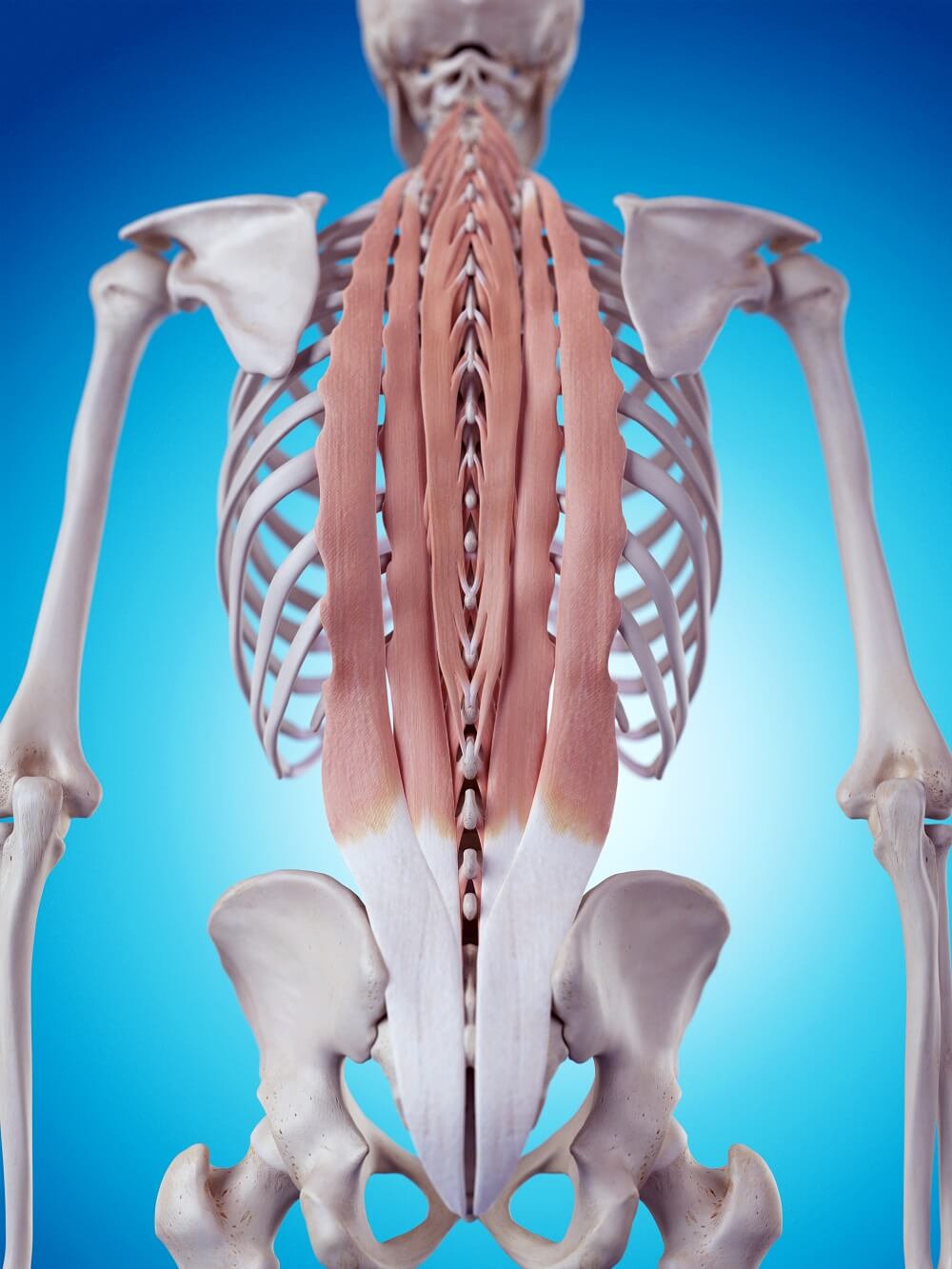

The erector spinae group contains three muscles than run either side of the spine. This means each muscle has a parallel partner connected by tendons – we can almost say we have two iliocostalis, two longissimus, and two spinalis muscles, although these are seen as single muscles.

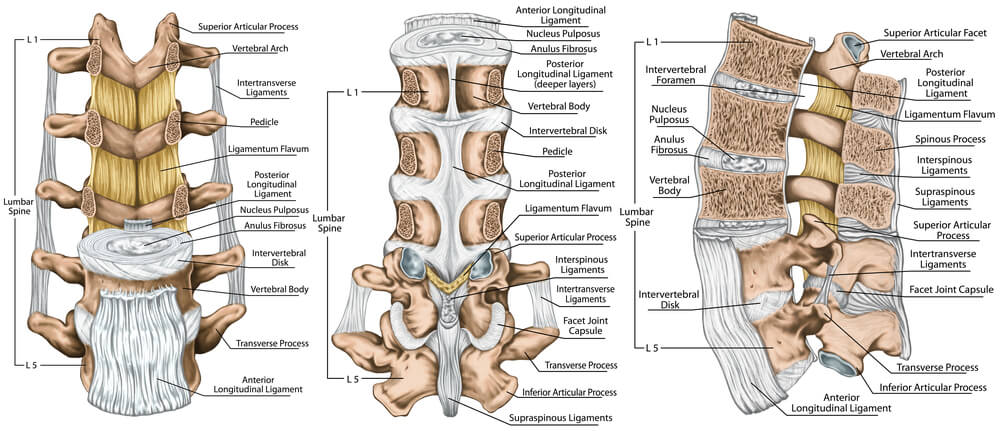

Because this muscle group shares common tendons and nerve pathways and have a similar function they are grouped together under the umbrella term of erector spinae. Longissimus, spinalis, and iliocostalis muscles are all innervated by the spinal nerves and attach to shared areas of tendon at the vertebrae, sacrum, iliac crest, and sacroiliac and supraspinous ligaments. You can see where the supraspinous ligament covers the vertebrae in the image below.

Muscle location depends on where each muscle starts (its origin) and stops (its insertion site). The origin of any muscle refers to its attachment site to a part of the body that does not move; the insertion point of a muscle tells us where the muscle causes movement by pulling a non-fixed part of the anatomy in the direction of the origin. This happens when the muscle contracts. That means that when you know the points of origin and insertion, you also know the direction of that muscle’s movement. As the spine consists of lots of small bones, there are also lots of erector spinae insertions.

Erector Spinae: Iliocostal Muscle

The musculus iliocostalis or iliocostal muscle is divided into the iliocostalis cervicis, iliocostalis thoracis, and iliocostalis lumborum. This might seem like a lot of tough Latin names but you only need to remember them once – cervicis relates to the cervical spine of the neck, thoracis to the vertebrae of the thorax, and lumborum to the lumbar spine or lower back. The neck part of the iliocostal muscle has its origins at the angles (curves) of the third to sixth ribs. Its insertion points are at the transverse processes of the fourth, fifth, and sixth cervical vertebrae. Transverse processes are located at either side of the spinous process (the part you can feel) of each vertebra. Of course, you don’t need to know the origin and insertions of each muscle, but when you picture them in your head, this information tells you that when the iliocostalis cervicis contracts, it brings the top of the neck (insertion) towards the upper ribs (origin).

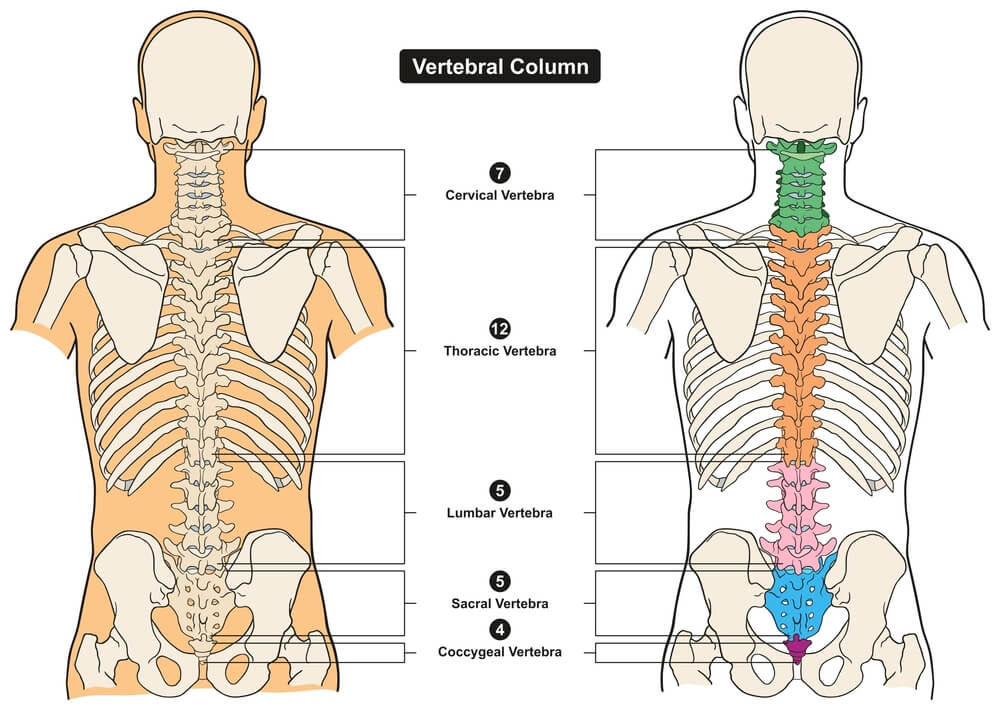

The thoracic section of the iliocostalis muscle originates at the angles (curves) of the seventh to twelfth ribs and inserts into the upper ribs (numbers one to six) and the transverse process of the seventh (lowest) cervical vertebra. The picture below shows how many vertebrae are associated with the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine. You can also see the transverse processes of the individual vertebrae sticking out to either side. So this muscle, whenever it contracts, pulls the upper ribs slightly downwards. This assists in a minor way with breathing in and out, but mainly allows us to bend forwards (forward flexion).

The lumbar part of the iliocostal muscle (iliocostalis lumborum) originates at the sacrum and iliac crest and has insertion points at the angles (curves) of ribs five through to twelve, and the transverse processes of L1 to L4. So you know that this also allows a downward movement of the back and lower ribs towards the pelvis.

But the iliocostal muscle does not work alone – it is only part of the erector spinae group and needs its partners to be effective – the longissimus and spinalis muscles.

Erector Spinae: Longissimus Muscle

The longissimus muscle is the largest of the three erector spinae. It runs from the shared tendon of the lower back all the way up to the skull. It is, in fact, the longest muscle of the human body – and of most vertebrates – but with a name like longissimus, that’s not surprising.

Again, we can split the spine into different sections. The only difference is that we add the skull – or rather a bony attachment point of the skull called the mastoid process – to give us the name for the highest point of the longissimus muscle – the longissimus capitis. Capitis means head. This part is followed by the longissimus cervicis, thoracis and lumborum. However, because the thoracic and lumbar parts act similarly they are usually grouped together as the longissimus thoracis et (and) lumborum.

The longissimus capitis originates at the transverse processes of C4 to T5 and insert at the mastoid process of the skull. Sometimes called the trachelomastoid muscle, it allows head extension (straightening), flexion, and rotation. The longissimus cervicis (neck) originates at T1 to T5 and inserts at the second to the sixth cervical vertebrae. Those neck rotating exercises you do when you have sat at the computer too long? They involve a lot of longissimus cervicis work! Finally, the longissimus thoracis (et lumborum) origins at L1 to L5 and various bones of the pelvis and inserts into all of the thoracic vertebrae, the angles of the seventh to twelfth ribs, and L1 to L5. If you can keep a hula-hoop going, you have great lower longissimus muscles!

Erector Spinae: Spinalis Muscle

The spinalis muscle runs closest to the spine and is split into the spinalis capitis, spinalis cervicis, and spinalis thoracis. It is not as long as the longissimus so does not have a lumbar area.

The origins of the spinalis capitis are the spinous processes (the sticking out bits you can feel) of vertebrae C7 to T1. These insert to the middle of the occipital bone at the back of the skull – so we know this top part pulls the head back. Spinalis cervicis origins are also at C7 to T1 but these insert into C2 and C3, bringing the very top of the spine towards the thorax. Finally, spinalis thoracis – with origins at T11 to L2 – brings the spinous processes of T2 to T8 towards the lower back.

Erector Spinae Exercises

Erector spinae exercises are often recommended for people with chronic lower back or neck pain. They are also popular with bodybuilders and help to lower the risk of injury in athletes. Everyone benefits from a good erector spinae workout as the different movements increase core body strength. What is very important is making sure you keep the correct posture if doing back exercises, especially if your back is damaged or weak.

The lowest portion of the erector spinae is highly visible in trained bodybuilders, even though more superficial muscles cover them further up. In the image below, the two linear bulges of the erector spinae can be seen on either side of the spine above the waistband before they disappear under the latissimus dorsi (flanks), rhomboid (mid thorax) and trapezius (below the neck) muscles.

Erector spinae strain is the result of sudden movement or long periods of sitting in a bad posture. The muscles elongate and stretch (bad posture) or lose mass and strength (inactivity). Chronic back problems often include erector spinae pain in the neck area, for example when constantly looking at a screen, or in the lower back due to slouching. By alternating periods spent seated with regular standing, walking, and stretching, pain can be postponed or even stopped.

A gentle erector spinae workout can be achieved through activities like yoga and Pilates. Specific back-strengthening exercises not only relieve pain, they significantly increase range of movement and core strength. Stretching this muscle group during periods of inactivity will eventually weaken its supportive effect in the spine, as this is a bit like constantly stretching a rubber band – eventually, the rubber band loses its elasticity and strength. By including regular movements that focus on contracting and relaxing the muscles that surround the spine, this elasticity and strength can be regained. Yoga positions such as the stretching cat and bird-dog have been proven to significantly improve core body strength, and these movements have very positive effects on erector spinae health.

Quiz