Definition

The zygomatic bone is a paired facial bone. Both zygoma or cheek bones are irregular and articulate with other bones of the cranium and face. They are important contributors to mastication or chewing, providing an attachment point for the masseter muscle – a jaw adductor that closes the jaw. In addition, the cheekbone contributes to the structure of the eye orbits and our ability to articulate.

Where is the Zygomatic Bone Located?

Zygomatic bone location can easily be felt as it forms the ridge above the fleshy area of the cheeks, along the outer rim of the eyes.

If you run your fingers along either ridge from the side of the nose, the first part you feel is the lower rim of the eye socket.

Continuing along this ridge, you will feel it lift to form the outer edge of the eye socket. Keeping your finger at the temple, just behind this part of the eye socket, start to open and close your mouth and clench your jaw. You will feel that there is a lot of muscle activity at this point.

Horizontal from the lower eye socket-ridge, you’ll feel a bony ridge extend to the upper ear. While the first portion is the cheekbone, the latter section is the zygomatic process of the temporal bone.

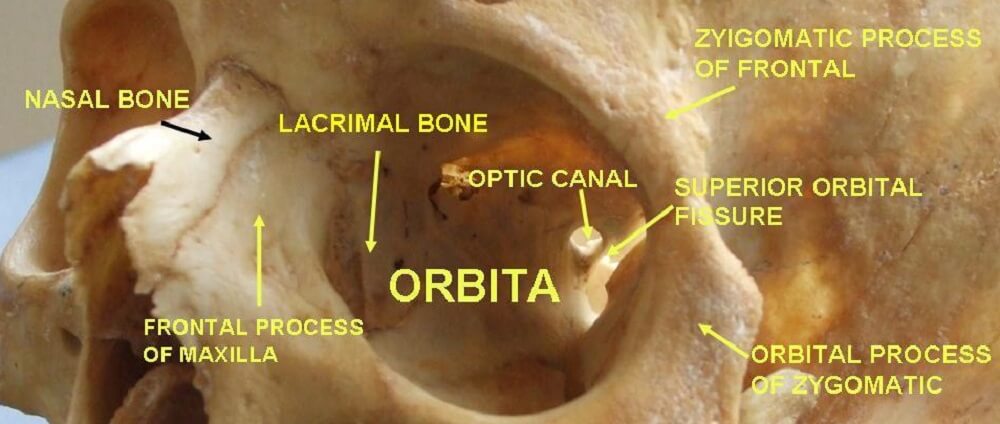

Both zygoma contribute to the outer edges of the orbital bones as well as the orbital floor.

Zygomatic Bone Anatomy

Zygomatic bone anatomy is not over-complex; its main function is to provide structure and strength to the mid-face.

The cheekbones have three surfaces, four processes, three foramina, and three articulations. Processes are projecting pieces of bone that insert into other bones.

It is always important to name the bone of origin as more than one can contribute to another structure. For example, orbital processes exist in the zygomatic, palatine, maxilla, and frontal bones.

Zygomatic Bone Surfaces

The lateral surface – or the facial surface – is what you can feel when pressing into the skin. From a lateral view, the zygoma are rectangular in form.

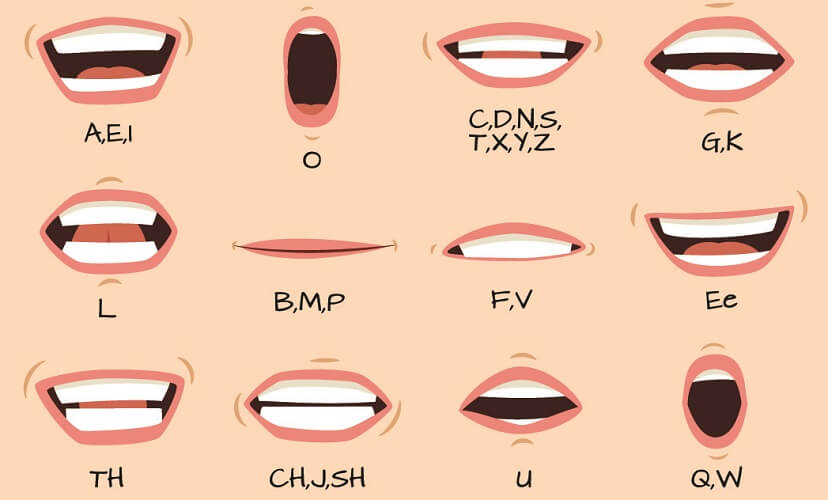

The lateral surface provides a point of attachment for the zygomaticus major and minor muscles. Both muscles are important for upper lip elevation – that’s smiling.

Another feature of the lateral surface is the zygomaticofacial foramen. More will be said about these nerve and blood vessel passageways further on.

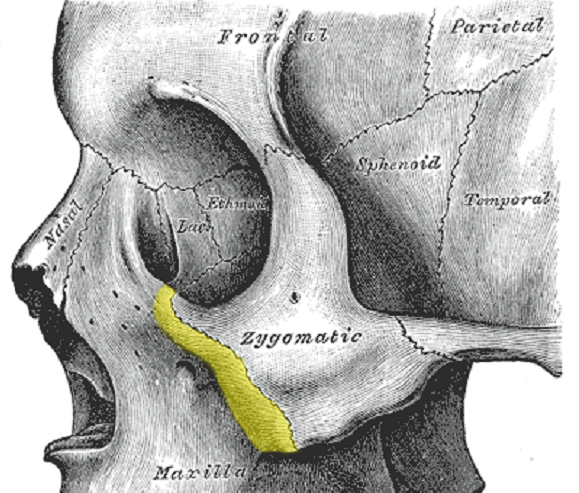

The temporal surface of the zygomatic bone faces the temporal bone of the cranium. It meets the zygomatic process of the maxilla bone and is concave in shape.

The temporal surface of the zygomatic bone articulates with the zygomatic process of the maxilla bone. Note how important it is to include the bone of origin – this avoids confusion.

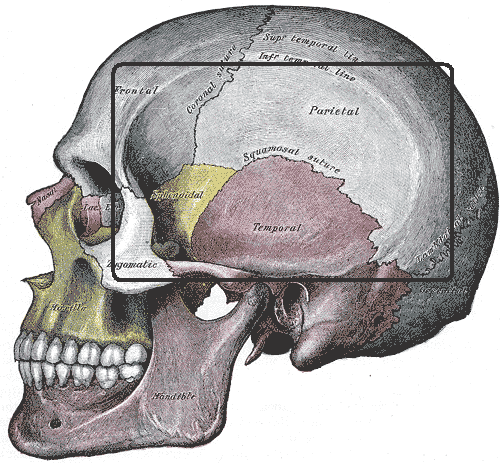

Opposite this articulation, the temporal surfaces of the zygoma provide borders that become the temporal lines. You can see that these lines begin at the cheekbone in the below image.

The third surface, the orbital surface, is concave. It faces the eye. It is the orbital surface of the zygomatic bone. This forms most of the outer, vertical part of the eye socket, and approximately half of the lower horizontal part.

Another foramen is found here – the zygomatico-orbital foramen. This hole leads to canals that travel to the zygomaticofacial and zygomaticotemporal foramina.

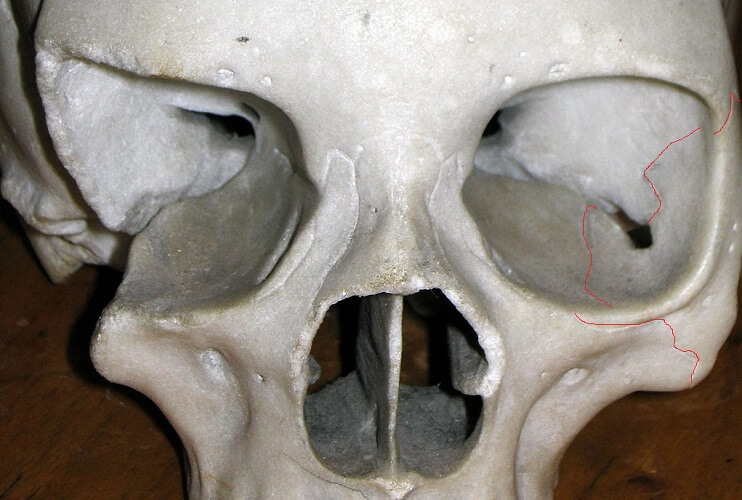

In the close-up view of the skull above, you can see several foramina.

Zygomatic Processes

There are four processes of the zygomatic bone, but these are not zygomatic processes! A process is named after the bone it meets with.

In the zygoma, these four processes are the:

- Orbital process of the zygomatic bone

- Maxillary process of the zygomatic bone

- Temporal process of the zygomatic bone

- Frontosphenoidal process of the zygomatic bone

Zygomatic processes, however, are found on other bones that extend into the zygoma. There are three zygomatic processes:

- Zygomatic process of the frontal bone

- Zygomatic process of the temporal bone

- Zygomatic process of the maxilla bone (or malar process of the maxilla bone)

Together with the temporal process of the cheekbone, the zygomatic process of the temporal bone forms the zygomatic arch.

This arch surrounds a large hollow that allows the temporal and masseter muscles to pass through to the lower jaw. It is this arch that gives the mid-face its shape. Broad arches, high arches, and flat arches make a visible difference to face shape.

A process is the point where one bone meets another but is not in itself an articulation.

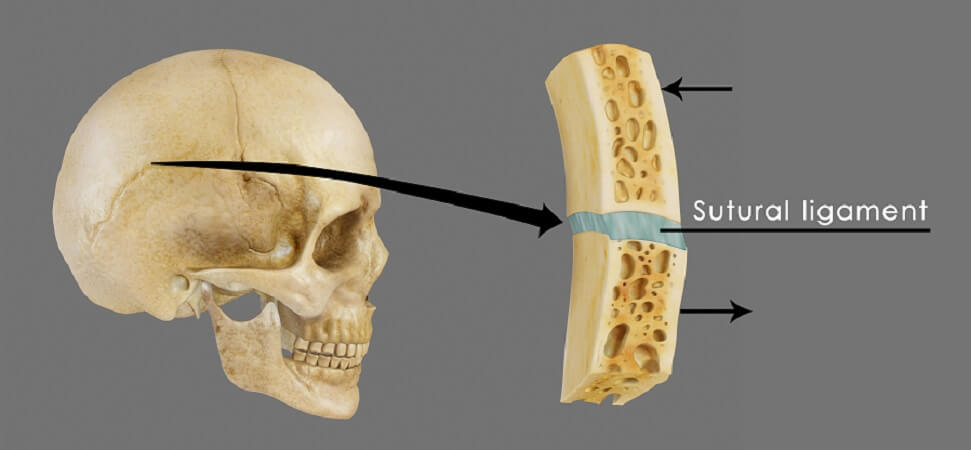

An articulation is a joint that may or may not provide movement (cranial sutures are joints or articulations). Zygomatic articulations occur between the singular frontal and sphenoid bones, and the paired temporal and maxilla bones.

These articulations are referred to as the ZMC complex (zygomaticomaxillary). The ZMC complex involves the:

- Zygomaticotemporal suture

- Zygomaticomaxillary suture

- Zygomaticofrontal suture

- Zygomaticosphenoidal suture

The ZMC complex is typically used to describe zygomatic bone fractures (more about cheekbone fractures later on).

Zygoma Muscle Attachments

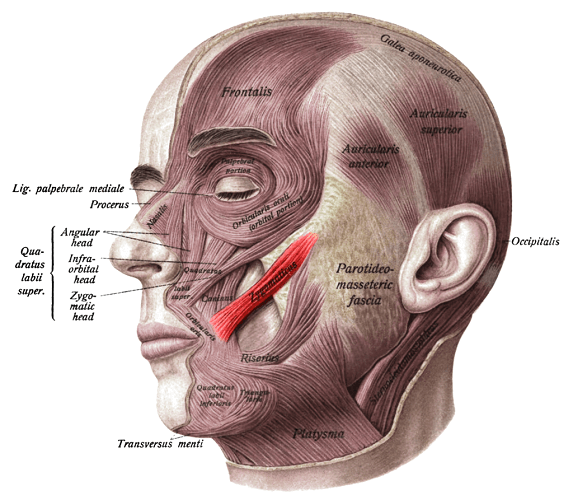

The zygoma provide attachment points for five muscles. Of these, only two originate at the cheekbone.

- Zygomaticus major

- Zygomaticus minor

- Masseter

- Lateral palpebrae ligament (part of the levator palpebrae superioris)

- Levator labii superioris (the origin is the maxillary border of the zygomatic bone)

The paired zygomaticus muscles bring the upper lips upward and out, helping us to smile.

The masseter – a powerful muscle that closes the jaw – has its origin at the zygomatic arch. It spreads from here to the lower jaw and provides enough pulling power to snap the lower jaw shut.

In humans, the average adult masseter provides a force of around 70 lbs. In 1882, doctors Regnard and Blanchard of the Sorbonne tested the power of the masseter of a medium-sized crocodile. They measured a force of 1540 lbs.

The levator palpebrae superioris elevates the upper eyelid. Its ligament is attached to the frontosphenoidal process of the zygomatic bone.

Finally, the levator labii superioris is a triangular band of muscle that stretches from under the eye sockets to the muscles of the upper lip. Its origin is at both the maxillary process of the zygomatic bone and the zygomatic process of the maxilla bone.

Like the zygomaticus muscles, it elevates the upper lip but more centrally. When you lift your lip to show your front teeth, you are making good use of your levator labii superioris. This same muscle dilates the nostrils of horses.

Zygomatic Foramina

As with many irregular bones, indentations and articulations provide passageways for important nerves and blood vessels. In the zygoma, these are the:

- Zygomaticofacial foramen

- Zygomaticotemporal foramen

- Zygomatico-orbital foramen

Grooves or canals sit between the zygomatico-orbital foramen and the two other foramina. These allow nerves to pass safely from eye to jaw.

The channel that starts at the zygomatico-orbital foramen and splits to exit from the zygomaticofacial and zygomaticotemporal foramina is called the zygomatic canal.

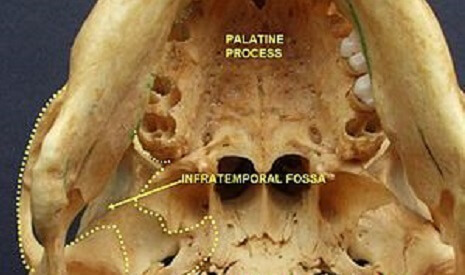

Another place where nerves and blood supply can pass through the bone is at the infratemporal fossa. A very graphic step-by-step dissection guide shows how to expose this fossa and its contents. The infratemporal fossa is a complex space; the zygomatic bone (the zygomatic arch) provides one of its borders.

The zygomatic nerve branches to form the zygomaticotemporal and zygomaticofacial nerves – each nerve exits from its similarly-named foramen:

- Zygomaticotemporal: innervates the lacrimal nerve (tear production) and the skin around the temporal fossa (indentation at the side of the skull).

- Zygomaticofacial: otherwise referred to as the malar branch, this nerve innervates the skin of the zygomatic arch and the upper cheek.

The buccal branch of the facial nerve (not the buccal nerve) is also associated with zygomatic bone function. It innervates muscles under the orbit and around the mouth.

Zygomatic Bone Function

Zygoma function is a simple subject. As we have already seen, this paired bone provides points for muscle attachment that enable facial expression and mastication. They also play an essential role in speech and articulation, coughing, and even breathing.

Important cranial nerve branches and blood supply pass through the foramina and canals of the zygoma. These provide sensory and motor signaling between the brain and the face.

As a thick, strong piece of bone – at least at its center – the zygomatic bone provides protection of the anterior skull base, as well as of the eyes. The zygomatic arch partially protects the weaker spot of the pterion – an area within the temporal fossa where many cranial bones meet.

The cheekbone naturally contributes toward how we look. Wide faces are commonly due to zygomatic arch protrusion. High cheekbones – the ideal bone structure in the modeling world – is also the result of zygomatic arch shape.

Zygoma reduction surgery reduces facial width; higher cheekbones involve the insertion of an implant or fillers.

Zygomatic Bone Fracture

A zygomatic bone fracture can cause long-term damage to any facial nerve that travels through or alongside it. Severe cases can cause unilateral facial paralysis.

The most common area of damage in this type of fracture is the zygomatic arch. It juts out and bears the brunt of the force. It is most commonly damaged during physical assault, contact sports, and road traffic accidents.

If not displaced, treatment is conservative. The person will be asked to rest and keep head movement and jolts to a minimum. He or she may not blow his or her nose, and should perhaps integrate a liquid diet until healing makes the fracture more stable. They will also need to keep exaggerated facial expression and highly-articulated speech to a minimum.

In the case of bone displacement – often at the orbit bones and zygomatic arch – surgery is required. A zygomaticomaxillary complex fracture (ZCM fracture) accounts for around 40% of midface fractures.

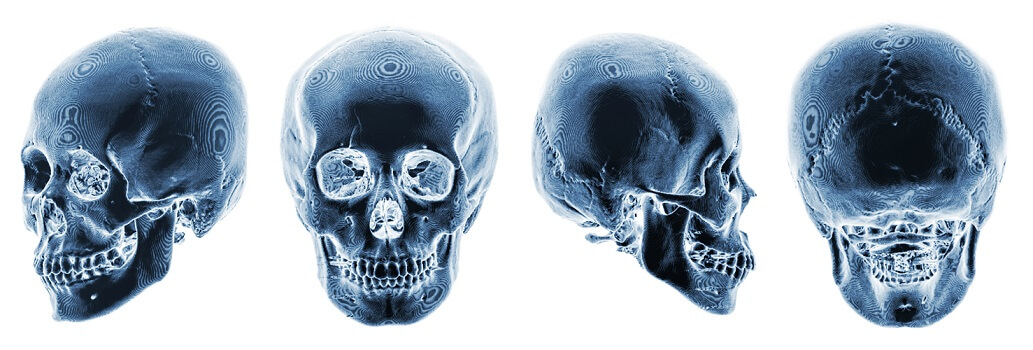

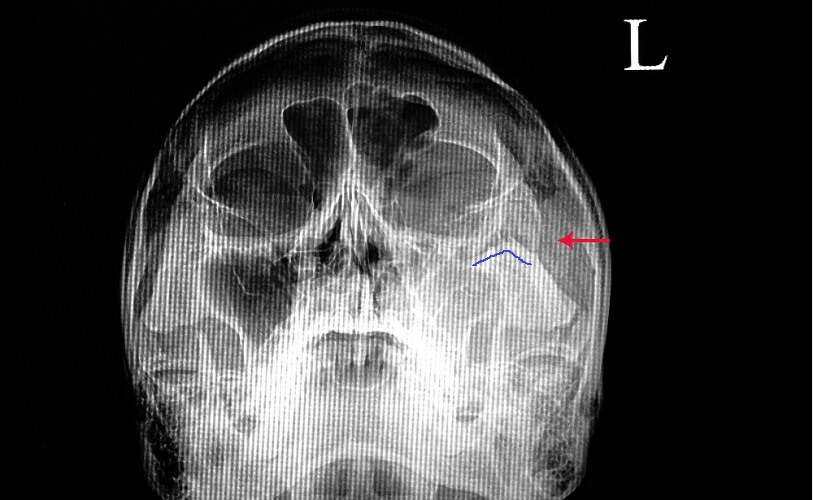

This fracture type typically requires surgery, especially when symptoms such as trismus (lockjaw) and hypesthesia (oversensitivity and pain) are present. This fractured zygomatic bone x-ray shows damage to the left eye socket and upper cheek. The blue line mimics the break-line above it.

Blowout fractures of the orbit may or may not fracture the left or right zygoma. The orbital rim stays intact and signs of fracture are not obvious. Double vision after a blow to the face – commonly by a fist or ball – is a possible indication of a blowout fracture. This describes the back of the eye socket being broken and perhaps damaging the eye-ball or optic nerve.