Definition

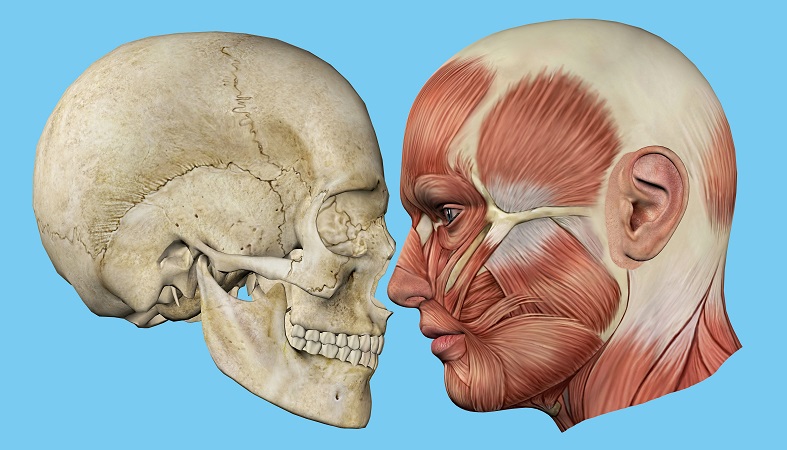

The frontal bone (os frontale) is an unpaired craniofacial bone that provides partial coverage of the brain and forms the structure of the forehead and upper casing of the eye sockets. It is composed of a squamous part, two orbital parts, and one nasal part. Muscles attached to and surrounding the frontal bone are essential for facial expression.

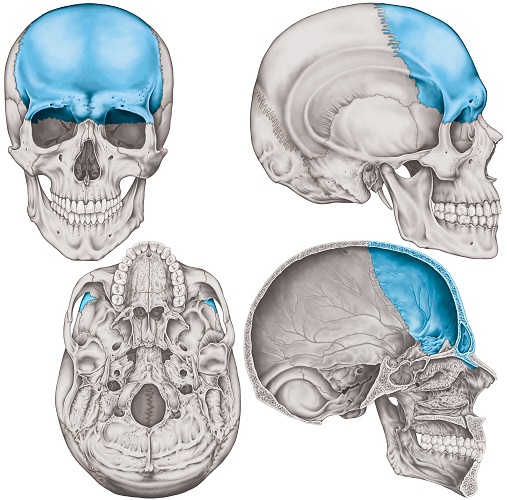

Frontal Bone Location

The location of the frontal bone is at the front of the cranium. As a craniofacial bone, it forms part of the rounded part of the skull and the upper face. You will see a variety of unlabeled and labeled frontal bone views below.

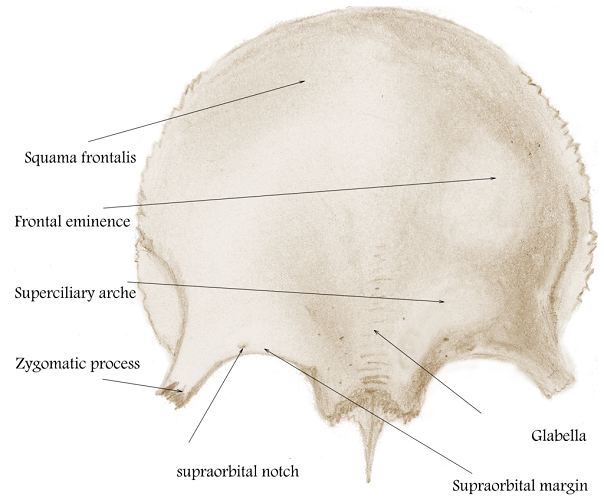

The squamous part of the frontal bone forms the structure of the forehead and eyebrows. The orbital parts create the upper section of both eye sockets. The nasal part joins to the nasal bones at the glabella, just between the eyebrows.

Frontal bone location should be looked at from different angles. If looked at from above, you will see its joints (sutures) with the left and right parietal bones – the most distinctive suture in this photograph.

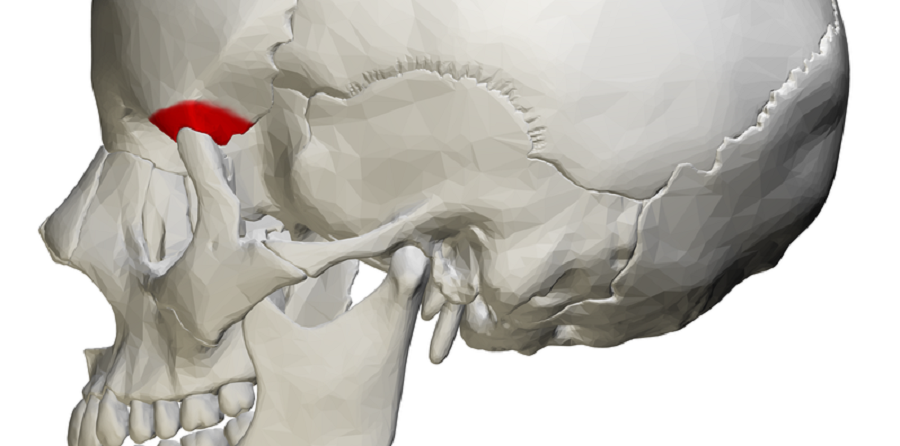

In lateral view (from the side), the os frontale features in an area of the skull where multiple bones meet – the pterion. The pterion is an anatomical location comprised of several sutures between the frontal, parietal, temporal, and sphenoid bones.

Each pterion lies just behind the temple (the indentation behind the outer rim of each eye socket) and is a known weak spot. The outer rim of the eye socket (orbit) can also be seen in the lateral view.

The glabella – the part of the os frontale that lies between the eyebrows – ends at the top of the nasal bones. The frontal bone is thicker at the eyebrows and this is usually more pronounced in male skulls. Where nasal bones and glabella meet is called the nasion – this dip is easy to see and feel.

A frontal view shows the horizontal line of upper orbit edges and glabella that indicate where the os frontal ends. At the lower forehead, it is a facial bone; above the eyebrows, a cranial bone.

Frontal Bone Anatomy

Frontal bone anatomy is not as complex as the anatomy of many smaller facial bones.

It features two main foramina (holes) that allow nerves and blood vessels to pass from one side of the bone to the other, as well as various grooves, prominences, and spaces that create protected areas and channels for soft tissue.

Frontal Bone Innervation

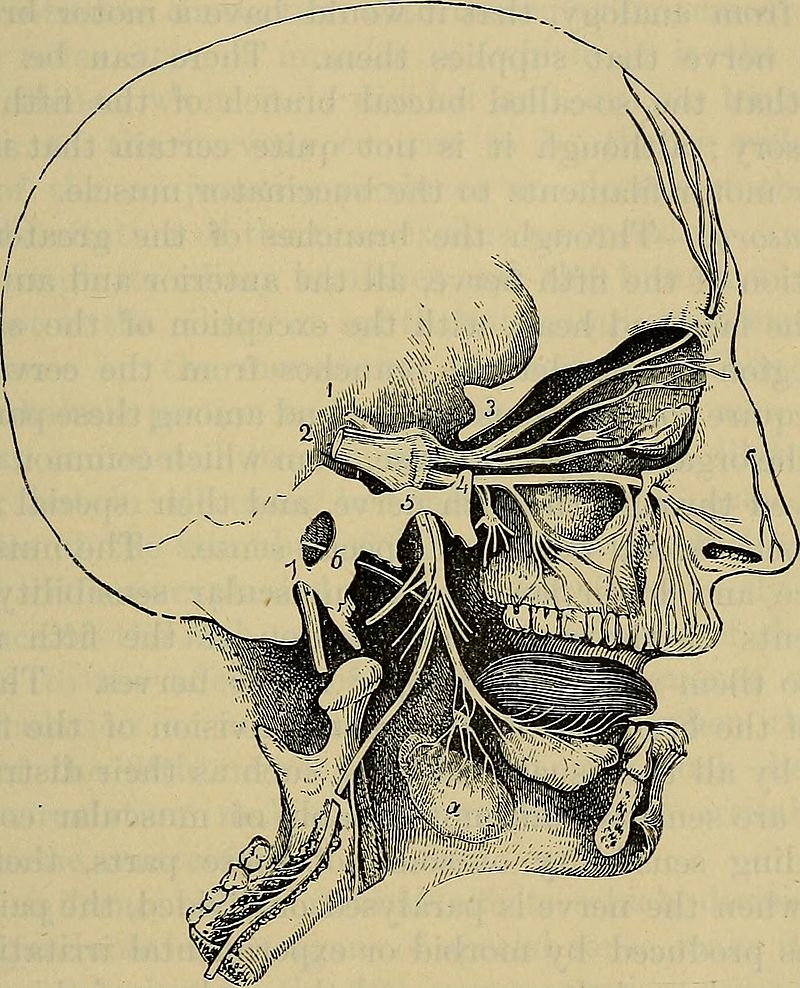

The skin of the forehead and upper scalp is innervated by the (sensory) ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve (CN V). This nerve travels through the left and right supraorbital foramina.

The left and right supratrochlear and supraorbital nerves (branches of the ophthalmic branch), together with arteries of the same name, pass through the left and right foramina of the frontal bone, at the supraorbital margin. In the below image, you can see CN V (1 and 2) branches move up towards the back of the eye. This is the opthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve that travels out of the top of the eye socket to innervate the forehead. The hole through which this nerve passes is the supraorbital foramen.

Muscles that attach to and surround the frontal bone are innervated by the facial nerve (CN VII). The most important of these are the orbicularis oculi, frontalis, and procerus muscles described under the next heading.

Often, one or both of the supraorbital foramina is not a complete hole but a notch. The supraorbital or frontal notch is simply an incomplete foramen. The notch is a more common finding.

Muscle Attachments

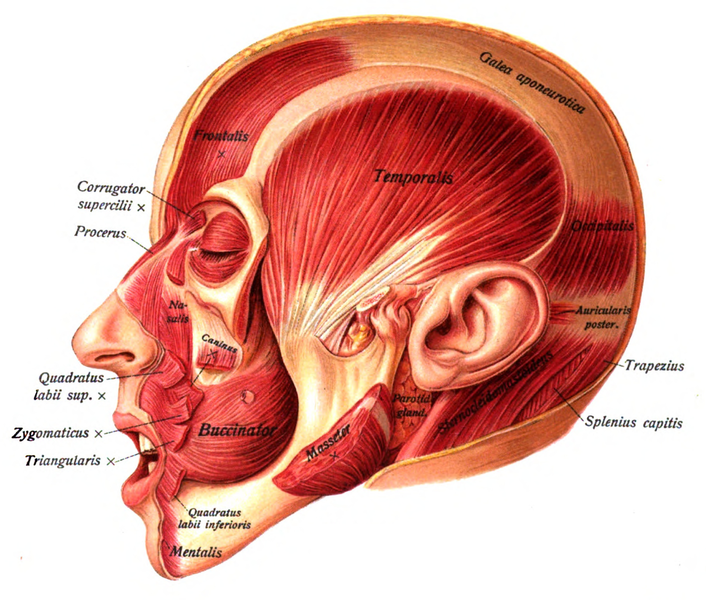

The long, wide occipitofrontalis (epicranius) muscle covers the top of the head from the back of the head to the eyebrows. It is divided into two bellies – the occipital and frontal bellies. The frontal belly (frontalis muscle) covers the forehead and has its origin at the galea aponeurotica – a large tendon that sits between both bellies.

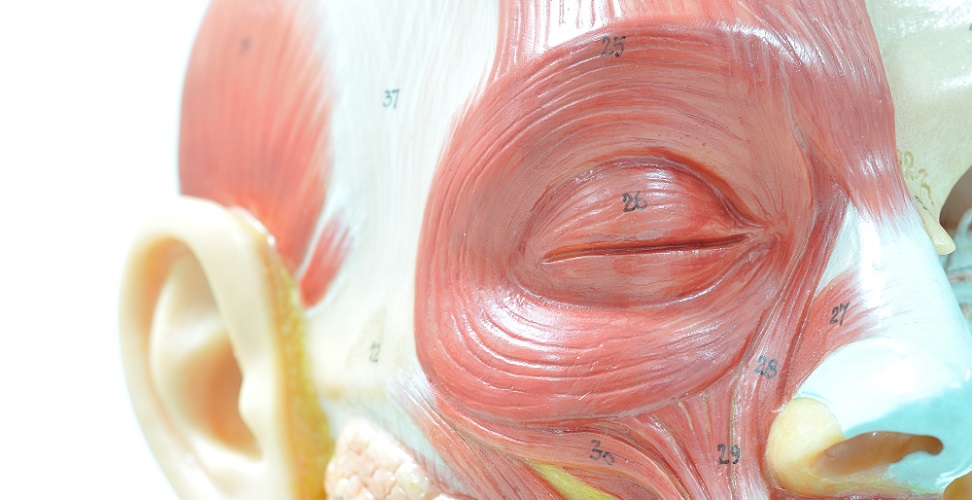

The frontalis muscle inserts at the eyebrows and pulls them back (raises them). The image shows the occipitofrontalis and the galea aponeurotica, as well as other muscles not attached to but associated with the frontal bone such as the procerus and corrugator supercilii.

The orbicularis oculi is a circular muscle that surrounds the eyes. It acts as a sphincter. The origin of the orbicularis oculi is the upper edge of the eye socket – the orbital part of the frontal bone. Muscle fibers of the orbicularis oculi blend with those of the frontalis muscle so when we raise our eyebrows or frown, the eye muscles also react.

The side or lateral surface of the frontal bone forms one edge of the temporal fossa. This is an indentation in the skull behind the eye that you can easily feel. The pteroid is located within the temporal fossa, together with various nerves and arteries and the temporalis muscle. The temporalis has no origin or insertion at the frontal bone but passes along its edge; it is a jaw-closing muscle.

The procerus muscles between the eyes (glabella) do not originate at the frontal bone either, but some of their fibers merge with fibers of the frontalis muscle. The procerus muscles are frontalis muscle antagonists, contracting when the frontalis relaxes and vice versa.

Other frontalis muscle antagonists are the corrugator supercilii muscle (inner eyebrow) and orbicularis oculi – number 25 in the below image.

Frontal Bone Articulations

The squamous part of the frontal bone joins the left and right parietal bones at the coronal suture. Close to the temple, this suture becomes part of the pterion – the meeting of two cranial (parietal and temporal) and two craniofacial (frontal and sphenoid) bones. The sutures form an H-shape on the side of the skull.

There are five sutures at the pterion:

- Sphenoiparietal suture – between sphenoid and parietal bones

- Coronal suture – between frontal, sphenoid, and parietal bones

- Squamous suture – between temporal, sphenoid, and parietal bones

- Sphenofrontal suture – between frontal and sphenoid bones

- Sphenosquamosal suture – between sphenoid and temporal bones

The frontal bone has a total of twelve articulations. Of these, only the two parietal bones are true cranial bones.

The ten other articulations are with six craniofacial bones.

- Sphenoid bone

- Ethmoid bone

- Nasal bones (x 2)

- Maxilla bones (x 2)

- Lacrimal bones (x 2)

- Zygomatic bones (x 2)

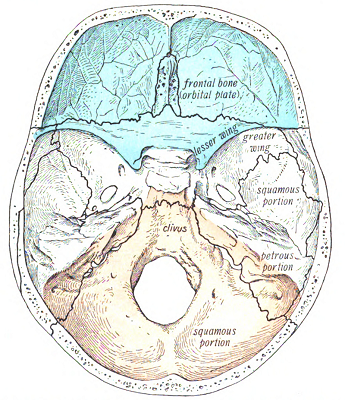

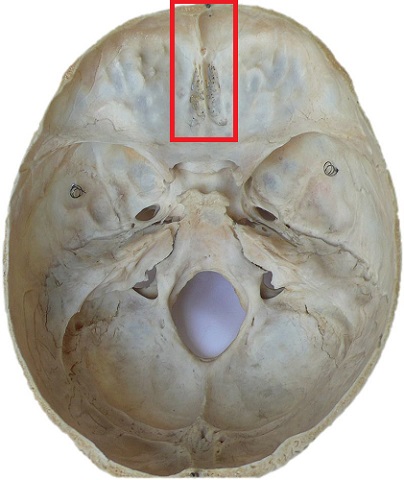

As already mentioned, one area of frontal-sphenoid articulation is at the pterion. However, within the forehead the frontal bone also articulates with the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone. Together with the ethmoid bone, these bones form a hollow region called the anterior cranial fossa. The anterior cranial fossa provides two compartments for the left and right frontal lobes of the brain.

Os frontale articulations with the top of the two nasal bones connect the nose to the glabella. Articulations with the two lacrimal bones help to form the eye socket but also create space for the lacrimal glands (tear glands). The frontal processes of the maxillary bones also articulate with the frontal bone inside the eye sockets. Process refers to a bony protrusion.

The zygomatic bone (cheekbone) articulates with the zygomatic process of the frontal bone. This occurs at the outer edges of each eye socket. The zygomatic process of the frontal bone is colored red in the following image.

Frontal Bone Bumps and Grooves

The frontal crest on the inner (inferior) surface of the os frontale (inside the anterior cranial fossa) is the starting point of a groove that runs through the center of the skull. While the frontal crest is a place of attachment for the membranes that cover the brain, the groove (sagittal sulcus) is a drainage point for cerebral blood.

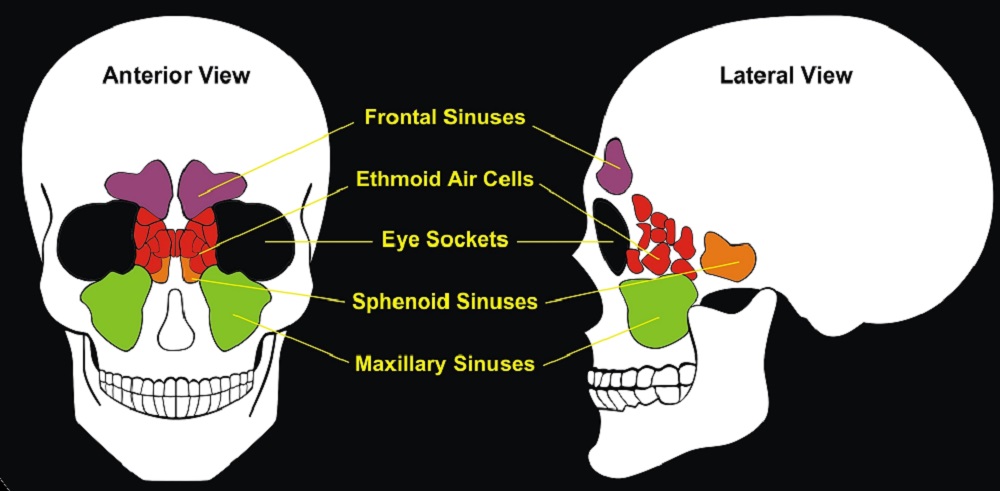

Opposite the frontal crest, above the glabella, is a thinner area of bone that creates a hollowed-out space. This is the frontal sinus. The paired frontal sinus bone is part of the network of paranasal sinuses that spreads out from the nasal cavity. Sinuses are lined with a layer of mucosa and protect the respiratory tract from foreign particles and potential pathogens as well as slightly warming and humidifying the air we breathe into our lungs.

At the orbital part of the frontal bone, the large left and right orbital plates form the upper casing of the eye sockets. These plates also feature indentations – lacrimal fossae – that house the tear glands.

The left and right orbital plates are separated by a gap called the ethmoidal notch, an articulation point between the frontal and ethmoid bones.

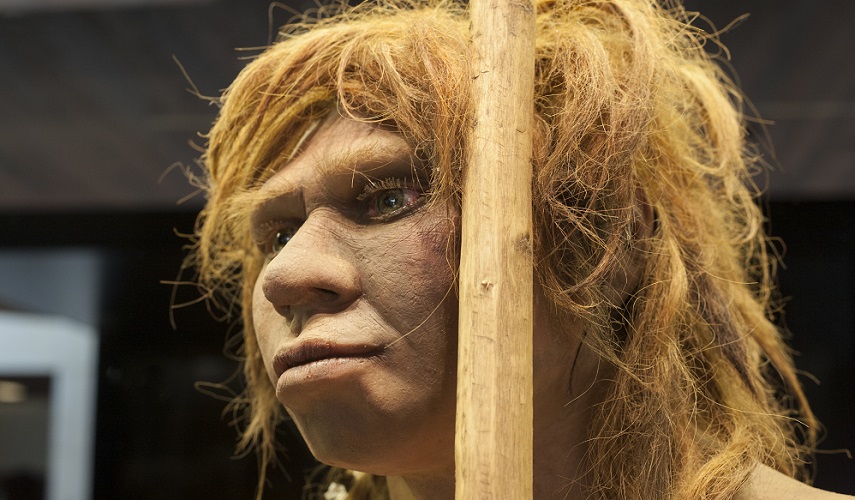

On the outer (superior) surface of the frontal bone, three distinct features can be seen or felt. The first is the superciliary arch, also called the brow ridge or supraorbital ridge. It is this ridge that helps forensic scientists determine whether unidentified human skulls are male or female and archaeologists to help figure out the period of ancient skeletal or fossilized remains.

The left and right frontal eminences (frontal tubers) lie approximately three centimeters above the supraorbital ridge. Some people call these the frontal bosses.

Forehead bossing describes very large frontal prominences and superciliary arches; it is associated with several genetic syndromes or acromegaly.

You will be able to feel these smooth forehead bumps on your own head but they are probably not very pronounced.

The final feature of the superior surface of the frontal bone is the left and right supraorbital margins. Each curved edge lies beneath the supraorbital ridge and defines where the orbital area of the face begins. The supraorbital foramina are located in the supraorbital margins.

Frontal Bone Function

Frontal bone function is a simple topic once you know a little about this bone’s anatomy and location.

- Provides structure to the skull, eye orbits, and upper face

- Protects the frontal lobe of the brain

- Contributes to innate immunity (frontal sinus bone)

- Allows important nerves and blood vessels to innervate the skin and muscles of the face (foramina)

- Aids facial expression (muscle attachments)

Frontal bone function also includes its articulations with other bones to provide complete anatomical structures, such as the joining of frontal, sphenoid, and ethmoid bones to create the anterior cranial fossa.

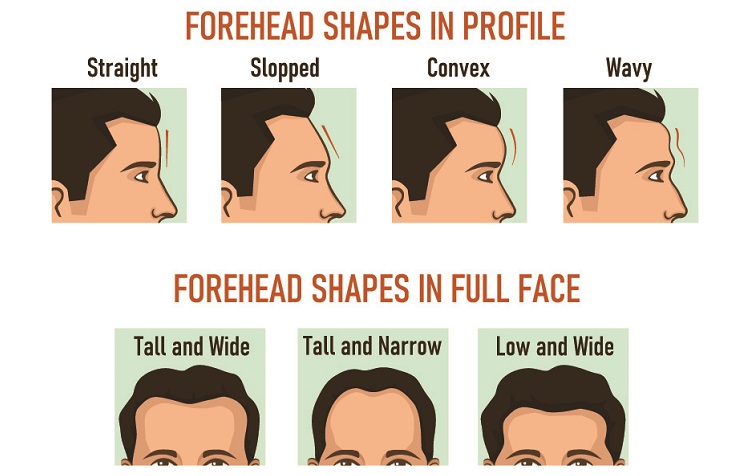

Finally, the os frontale plays a major role in our appearance. Wide or high foreheads, prominent, bumpy, or smooth eyebrows – the frontal bone is very responsible for how we look.

Frontal Bone Fracture

Os frontale fractures are quite uncommon, primarily because the skull is thicker and sturdier than the smaller, often fragile, facial bones. However, any fracture of the frontal bone can cause permanent changes to our appearance if not treated by a maxillofacial expert.

The most common cause of frontal bone fracture is assault; the weak spot of the pterion is particularly at risk. Such an injury is usually the result of a kick to the side of the head.

Facial injuries that break other upper facial bones may cause frontal bone fractures but only in around 5% of cases. The larger, thicker os frontale is more likely to withstand blunt force trauma but can exert pressure on the delicate bones that surround it and cause more widespread damage. A depressed frontal bone fracture, although relatively rare, can cause permanent disfigurement.

Damage to the membranes surrounding the brain and the frontal lobe of the brain is possible, either through increased pressure of the bone against the soft tissue or penetration by small bone fragments. Bleeding at the pterion is likely as it shares its temporal fossa location with deep and superficial temporal arteries.

The frontal bone sinus may be permanently lost when fractured; however, a force of up to 1500 ft-lb (2033 Newton-meters) is required. This is more than twice the force needed to fracture other facial bones; the equivalent of being punched in the face by Floyd ‘Money’ Mayweather or being host to a well-placed facial kick from a martial arts specialist.

Quiz